Arthrose : Weizmann crée un hydrogel (Liposphere, Israël) qui réduit les frottements articulaires d'un facteur 100

[:fr]

L’arthrose, qui conduit à la destruction du cartilage articulaire, représente un véritable problème de santé publique dans les pays développés. « En France, l’arthrose touche 9 à 10 millions de personnes, soit 17 % de la population. Entre 1993 et 2003, le nombre de personnes atteintes a augmenté de 54 %. Seconde cause d’invalidité, elle est un véritable handicap pour de nombreux patients. Coût estimé : 3 milliards d’euros par an », selon l’Alliance Nationale Contre l’Arthrose (stop-arthrose.org).

L’Institut Weizmann des Sciences a fait une avancée extraordinaire pour résoudre le problème de l’arthrose grâce aux travaux de ses chercheurs et à la start-up Liposphere nommée en 2020 «l’une des 44 entreprises les plus prometteuses issues des milieux universitaires dans le monde » Nature. Esther Amar, fondatrice et directrice de Israël Science Info souligne « l’importance capitale de cette innovation ».

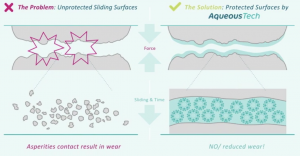

Le cartilage qui protège nos articulations est un merveilleux système qui absorbe les chocs et lubrifie les articulations, permettant aux os de glisser facilement les uns contre les autres. Il résiste à une forte pression et subit un état de friction constante, décennie après décennie, mais il s’use à peine. Inspirés par la composition du cartilage, les chercheurs de Weizmann ont créé de nouveaux types d’hydrogels qui réduisent le frottement des dizaines de fois mieux que les hydrogels existants, ouvrant ainsi la voie à une variété de nouvelles applications biomédicales. Ces nouveaux gels ont été jusqu’à 100 fois meilleurs pour réduire le frottement et l’usure que les hydrogels actuels.

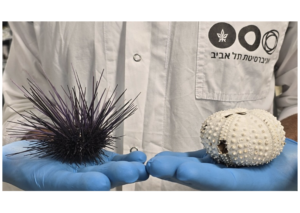

Depuis deux décennies, l’équipe du Prof. Jacob Klein, du département de chimie moléculaire et de science des matériaux à Weizmann cherche à comprendre les propriétés lubrifiantes de la couche la plus externe de cartilage de nos articulations, ce qui le rend si résistant et efficace, et comment atténuer les effets de son usure, par exemple, dans le cas de l’arthrose. Cette couche a un coefficient de frottement plus faible que n’importe quel matériau synthétique. Ils ont découvert que les effets lubrifiants sont basés sur les lipides, les mêmes molécules grasses qui composent les cellules et les autres membranes du corps.

Depuis deux décennies, l’équipe du Prof. Jacob Klein, du département de chimie moléculaire et de science des matériaux à Weizmann cherche à comprendre les propriétés lubrifiantes de la couche la plus externe de cartilage de nos articulations, ce qui le rend si résistant et efficace, et comment atténuer les effets de son usure, par exemple, dans le cas de l’arthrose. Cette couche a un coefficient de frottement plus faible que n’importe quel matériau synthétique. Ils ont découvert que les effets lubrifiants sont basés sur les lipides, les mêmes molécules grasses qui composent les cellules et les autres membranes du corps.

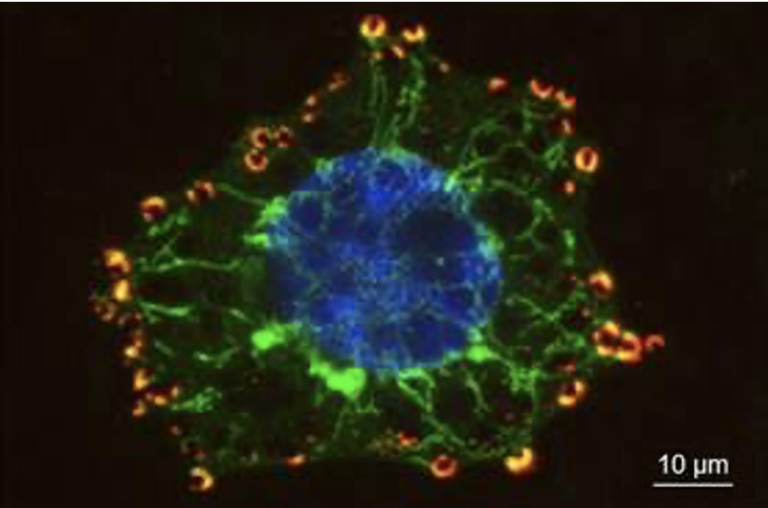

Ces molécules ont une tête et une queue : la queue est hydrophobe (déteste l’eau), et la tête est hydrophile (aime l’eau). Lorsque ces molécules sont positionnées du côté qui aime l’eau, la surface du cartilage s’hydrate. Les propriétés chimiques et électriques de cette couche la lient étroitement à la surface du cartilage, ce qui la rend résistante à la pression tout en la maintenant bien lubrifiée avec une fine couche de fluide réduisant le frottement qui permet aux os à nos articulations de glisser, pivoter et pivoter pendant des années.

La nouvelle étude, le Pr Jacob Klein et le Dr Ronit Goldberg, ancien doctorante de son groupe, avec le chercheur Dr. Weifeng Lin, stagiaire postdoctorant Dr. Monika Kluzek et le scientifique principal Dr. Nir Kampf, avec le Dr. Eyal Shimoni, du département de soutien à la recherche chimique, présente de nouveaux hydrogels inspirés de cette couche lubrifiante à la surface du cartilage. Ils ont inséré des «microréservoirs» de divers lipides dans les gels. Ces lipides sont libérés lorsqu’il y a frottement agissant sur la surface du gel.

«Dans les systèmes vivants, des molécules comme les lipides complexes sont créées dans les cellules, et elles sont stockées ou exportées dans de minuscules vésicules, ou liposomes. Nous avons utilisé cette idée dans nos hydrogels synthétiques pour créer des réservoirs microscopiques de lipides répartis dans tout le gel », explique Jacob Klein. «Alors que le frottement et l’usure décollent un peu de la surface du gel (plus de microns à la fois) de nouveaux lubrifiants lipidiques sont exposés. De cette façon, la lubrification en surface est continuellement renouvelée. »

Cela pourrait également conduire au développement d’articulations artificielles capables de mieux résister à l’usure, de sorte que les articulations de remplacement durent plus longtemps et causent moins de problèmes que celles placées aujourd’hui. Pour faire avancer ces différentes applications, la start-up Liposphere a été créée en 2019 sous licence de Yeda R&D, branche de transfert de technologies de Weizmann. Ses fondatrices sont les Drs. Ronit Goldberg, PDG et Sabrina Jahn, ancienne postdoctorante du Pr Klein.

Cela pourrait également conduire au développement d’articulations artificielles capables de mieux résister à l’usure, de sorte que les articulations de remplacement durent plus longtemps et causent moins de problèmes que celles placées aujourd’hui. Pour faire avancer ces différentes applications, la start-up Liposphere a été créée en 2019 sous licence de Yeda R&D, branche de transfert de technologies de Weizmann. Ses fondatrices sont les Drs. Ronit Goldberg, PDG et Sabrina Jahn, ancienne postdoctorante du Pr Klein.

[:en]

What copes with heavy pressure and exists in a state of constant friction, decade after decade, yet barely gets worn down? The answer is the cartilage padding our joints – actually a marvelous system that both absorbs shocks and lubricates the joints, allowing bones to slide easily against one another. Inspired by the makeup of cartilage, Weizmann Institute of Science researchers have created new kinds of hydrogels that reduce friction tens of times better than existing hydrogels, and which may have a variety of new biomedical applications.

The group of Prof. Jacob Klein in the Institute’s Molecular Chemistry and Materials Science Department has, for the past two decades, been seeking better insight into the lubricating properties of the outermost layer of cartilage in our joints. They want to understand both what makes it so durable and efficient and how to alleviate the eventual effects of its wear and tear – for example, osteoarthritis. This layer has a lower friction coefficient – a means of measuring how much effort is involved in sliding one material against another – than any man-made material. The lubricating effects, they have found, are based on lipids – the same fatty molecules that make up cell and other membranes in the body.

These molecules have a head and a tail: The tail is hydrophobic, or “water-hating,” the head, hydrophilic, or “water-loving.” When these molecules are organized with their water-loving sides out, the cartilage surface becomes hydrated. The chemical and electrical properties of this layer bind it tightly to the cartilage surface, making it resilient under pressure but keeping it well lubricated with a thin, friction-reducing fluid layer that enables the bones in our joints to slide, swivel and pivot for years on end.

These molecules have a head and a tail: The tail is hydrophobic, or “water-hating,” the head, hydrophilic, or “water-loving.” When these molecules are organized with their water-loving sides out, the cartilage surface becomes hydrated. The chemical and electrical properties of this layer bind it tightly to the cartilage surface, making it resilient under pressure but keeping it well lubricated with a thin, friction-reducing fluid layer that enables the bones in our joints to slide, swivel and pivot for years on end.

The new gels performed up to 100 times better at reducing friction and wear than regular hydrogels

In the new study, Klein and Dr. Ronit Goldberg, a former doctoral student in his group, together with research fellow Dr. Weifeng Lin, postdoctoral fellow Dr. Monika Kluzek and Senior Staff Scientist Dr. Nir Kampf, with Dr. Eyal Shimoni of the Chemical Research Support Department, created new hydrogels inspired by that lubricating layer on the cartilage surface. They inserted “microreservoirs” of various lipids into the gels. These lipids are released when there is friction acting on the gel’s surface.

“In living systems, molecules like complex lipids are created within the cells, and they are stored or exported in tiny vesicles, or liposomes. We used that insight in our synthetic hydrogels to create microscopic lipid ‘stores’ or reservoirs distributed throughout the gel,” explains Klein. “As the friction and wear take off a bit of the gel surface – mere microns at a time – new lipid lubricants get exposed. That way, the lubrication at the surface is continually renewed.”

The new gels performed up to 100 times better at reducing friction and wear than regular hydrogels. That remained the case even when the group tested them by applying different speeds or contact with different materials – for example, metal or glass. And they found that if the gels dried out, they could be rewetted without harming their lubrication abilities – a property that could give them long shelf life and that suggests innovative new uses.

Already on their way out of the lab

Hydrogels are mainly water, with very small amounts of other additives. That makes them safe to use in contact with the body’s soft tissue, and this has led to their widespread use in the biomedical industries. A commonly used example is soft contact lenses. A new gel with better lubricating properties could have applications in the near future in uses such as stent insertion and tissue engineering. It could also lead to the development of artificial joints that can better withstand wear and tear, so that replacement joints last longer and cause fewer problems than those inserted today. To advance these various applications, a startup called Liposphere was established in 2019 under license from Yeda Research and Development, the technology transfer arm of the Weizmann Institute of Science. Its founders are Drs. Ronit Goldberg (who is the CEO) and Sabrina Jahn, another former postdoctoral student in Klein’s group. In 2020, Nature and Merck named Liposphere “one of the 44 most exciting, science-based firms spun out from academic environments” worldwide.

Prof. Jacob Klein’s research is supported by the Edmond de Rothschild Foundations; the McCutchen Foundation; Sonia T. Marschak; the Harold Perlman Family; and the European Research Council. Prof. Klein is the incumbent of the Hermann Mark Professorial Chair in Soft Matter Physics.

Prof. Jacob Klein’s research is supported by the Edmond de Rothschild Foundations; the McCutchen Foundation; Sonia T. Marschak; the Harold Perlman Family; and the European Research Council. Prof. Klein is the incumbent of the Hermann Mark Professorial Chair in Soft Matter Physics.

Publication in Science oct 2020

[:]