Canal mer Morte – mer Rouge : les travaux vont démarrer en 2018

[:fr]e-rse.net La mer Morte voit son niveau baisser d’un mètre par an depuis 1970. Cette mer cristallise tous les problèmes géopolitiques du Moyen-Orient : une rareté de la ressource en eau, des besoins importants pour l’agriculture et l’eau potable, une manne touristique fragile et une écologie qui passe bien souvent au dernier rang des préoccupations.

Ainsi la Mer Morte est en passe de… mourir. Son assèchement n’est qu’une question d’années tant les prélèvements s’accroissent dans sa principale source d’alimentation, le fleuve Jourdain. Pour empêcher ce funeste destin, la Jordanie et Israël ont décidé de réagir en construisant un gigantesque pipeline de 180 km de long reliant la Mer Rouge à la Mer Morte. Ce canal souterrain sera accompagné par la plus grande usine de désalinisation d’eau de mer. L’objectif ? Ni plus ni moins que résoudre la pénurie d’eau potable de la région et sauver le trésor culturel qu’est la mer Morte.

La mer Morte, un enjeu avant tout économique

Si Israël et la Jordanie ont décidé de mettre de côté leurs rancœurs c’est bien parce que l’enjeu économique est primordial pour la région. L’eau du Jourdain, qui alimente la mer morte, est prélevée à 95% par les pays riverains pour l’agriculture tandis que le tourisme représente une part toujours plus importante de l’économie du Royaume de Jordanie. A 429 mètres au-dessous du niveau des mers, la mer la plus basse du monde est en train de s’assécher, en menaçant le tourisme balnéaire et patrimonial.

Le site traditionnel du baptême du Christ dans le Jourdain, les grottes de Qumran où furent découverts les manuscrits de la mer Morte, et l’attraction de la mer en elle même drainent des millions de touristes tous les ans pour les pays riverains, dont les eaux très salées sont réputées en balnéothérapie. Son exceptionnel taux de salinité, 247 grammes par litre contre seulement 9 pour la méditerranée en fait une attraction recherchée… Mais en danger.

L’activité d’extraction de minéraux par évaporation est aussi responsable de l’assèchement de la mer Morte. Chaque année, 600.000 tonnes de sel y sont extraites et sont utilisées dans l’industrie agroalimentaire ou cosmétique.

La Jordanie est a présent le second pays le plus pauvre en eau. Entre une mauvaise gestion de la ressource, due à une fraude importante au compteur ainsi qu’un prix du m3 insuffisant, le royaume hachémite a désespérément besoin de cette ressource vitale pour sa population, qui augmente brutalement depuis quatre ans sous l’afflux d’un million et demi de réfugié en provenance de Syrie.

Il y a donc urgence : si la mer disparaît comme il est prévu dans 30 ans, c’est la population et toute l’économie de la région qui va en pâtir, ce qui renforcera les tensions géopolitiques déjà existantes.

Le “canal de la paix” pour sauver la Mer Morte

C’est une idée vieille de 50 ans qui commence enfin à se concrétiser : le 28 Novembre la Jordanie a annoncé avoir choisi les cinq consortiums internationaux (France, Japon, Chine, Singapour, Canada) regroupant près de 20 entreprises pour lancer les travaux à partir de 2018.

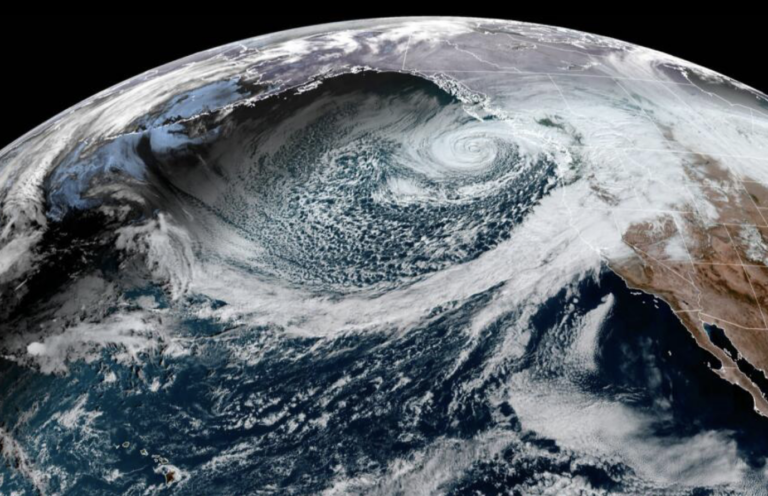

The water surface of the Dead Sea has shrunk dramatically – from 950 km2 square kilometres to 637 km2. The illustration shows the sea picture in 1972 and then in 2011

Cette première phase prévoit la construction d’un pipeline de 180 Km pour relier la mer Rouge à la mer Morte, ainsi qu’une usine de dessalement pour apporter de l’eau douce à toute la région. Financé en partie par la Banque Mondiale et des pays donateurs, le projet a véritablement été lancé par les accords de coopération de 2013 entre Israël, la Jordanie et la Cisjordanie occupée, ce qui lui vaut le surnom de “canal de la paix”.

Les chiffres sont pharaoniques : l’usine doit pouvoir traiter à terme 85 millions de m3 par an, ce qui en ferait la plus importante au monde, tandis que 300 millions de m3 d’eau seraient déversés dans le pipeline à partir du captage en mer Rouge.

Cette première phase est estimée à un milliard de dollars, tandis que la totalité du projet se monterait à terme à 10 milliards de dollars !

Cette gigantesque entreprise est censée sauver la mer Morte de sa lente agonie, qui voit son niveau baisser d’un mètre par an depuis 1970. Mais les ONG locales s’inquiètent de l’impact du déversement brutal d’une telle quantité d’eau de mer, qui pourrait entraîner le développement d’algues rouges et de cristaux de gypse. Dans son étude de faisabilité, la banque Mondiale a elle même reconnu un risque écologique, toutefois maîtrisable.

De même, l’usine de dessalement ne satisfait pas les associations qui pointent son manque d’ambition et ses immenses besoins d’énergie. Friends of the Earth Middle East (FOEME) dénonce également un prix de l’eau inabordable pour les populations locales : pour ces ONG une réforme en profondeur du système de distribution d’eau est nécessaire pour faire des économies.

Sauver la mer Morte permettra aussi à Israël d’y trouver son compte en évitant une renégociation des accords de partage des eaux du Jourdain, qui sont très favorables à son agriculture. Le canal devrait permettre aux agriculteurs locaux de pouvoir puiser dans le fleuve sans s’inquiéter d’impacter la mer Morte.

Le “canal de la mer Rouge à la mer Morte”, son nom officiel, devra donc permettre de stabiliser la région en évitant une de ces fameuses “guerre de l’eau” que l’on nous promet régulièrement. Sécurisation de l’approvisionnement en eau potable, sauvetage des activités touristiques et économiques de la mer Morte, pacification des relations dans cette région trop souvent explosive : à première vue, que des avantages. Mais vu l’ampleur pharaonique des travaux envisagés et leur côté totalement novateur, ce brillant succès diplomatique pourrait très bien se transformer en désastre écologique si seuls les intérêts économiques continuent de primer.

Source Niels de Girval pour e-rse.net

Ingénieur-Juriste, Niels de Girval est spécialisé sur l’étude du littoral j’ai fondé le bureau d’étude IG.REC afin de faciliter l’acquisition de données à bas coût sur les environnements côtiers. Enseignant vacataire à l’Université de Bretagne Sud il relie l’ingénierie littorale au droit de l’environnement pour enseigner la préservation de ces espaces naturels exceptionnels.[:en]he $10 billion Red Sea-Dead Sea project will see the joining of two oceans in the Middle East to transport millions of cubic metres of seawater.

It took a miracle for Moses to part the waters of the Red Sea. But as if to adduce evidence that divine intervention is not always required, the ambitious $10 billion Red Sea-Dead Sea conduit project was recently signed between Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian authorities.

The historic agreement received its official seal of approval through the World Bank just two weeks before Christmas and has been heralded as the solution to Jordan’s water deficit and the Dead Sea’s ongoing and dramatic environmental degradation.

The multinational proposal is to build a 180 km pipeline engineered to carry up to two billion cubic metres of seawater per year from the Gulf of Aqaba on the Red Sea through Jordanian territory to the Red Sea.

In fact the notion of connecting the two seas by a conduit or canal is nothing new. Back in the late 19th century planners had pondered how to use the Jordan River for irrigation and to bring water to the Dead Sea. But like many well-intentioned projects in the Middle East and much talk of ‘saving the Dead Sea’ nothing actually happened.

Meanwhile the Dead Sea itself, considered by some as both the cradle of human culture and civilisation, has fallen from 394 meters below sea level in the 1960s to 423 meters below sea level today. The water surface has also shrunk dramatically – from 950 km2 square kilometres to 637 km2. Unlikely to dry up completely, it is predicted that its surface will diminish to an estimated 300 km2, with the water level continuing to drop at the alarming pace of one meter per year.

The multinational proposal is to build a 180-kilometre pipeline engineered to carry up to two billion cubic metres of seawater per year from the Gulf of Aqaba on the Red Sea through Jordanian territory to the Red Sea

Yet Friends of the Earth Middle East (FoEME) and other environmental groups have countered that the mega-project was fatally flawed from the outset. They argued that the only sustainable solution is to tackle the source of the problem by rehabilitating the Jordan river which, since time immemorial, has fed the Dead Sea with fresh water. Such fresh water is now singularly lacking courtesy of massive diversions in the form of dams, canals and pumping stations constructed by Israel, Syria, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority alike.

Standing pensively on the shores of the Dead Sea Gidon Bromberg, Israeli director of FoEME, points to a now defunct hotel which had originally been built by the shoreline.

« You see that building. It’s now over one kilometre away, » he laments. « And you know why? Because 98% of the flow of the Jordan River, which feeds the Dead Sea, has been diverted. Plus the World Bank is talking about three pipelines, a very large pipe according to the bank’s own report that would be some 60 meters in width – so we are also talking about a major scar on the landscape, massive pipes which would run above ground for the best part of 200 kms. »

And yet Jordan has been the strongest proponent of the Red-Dead canal, as it is known in environmental circles. It’s easy to see why: the country’s access to fresh water is among the most restricted in the world. One of the world’s four poorest countries in respect of its water resources, Jordan produces around 880 billion cubic meters distributed over drinking household consumption and other economic activities and agriculture which alone consume 58% of total water. Water rationing is a part of everyday life.

A situation now made all the more acute by the influx of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees fleeing from that country’s long and bitterly fought out (and ongoing) civil war.

This explains why Saad Abu Hamour, secretary general of the Jordan Valley Authority and Jordanian head of the Israel-Jordan Joint Water Committee has gone out of his way to reaffirm his country’s ongoing support for the proposed conduit. « Potable water is a priority in Jordan and we are trying to secure it by linking the two seas, » he explains.

FoEME’s Munqeth Mehyar takes issue with this view. « The whole plan takes place on Jordanian territory, » he says from his office in Amman. « But Jordan is being hard-hit by the global economic downturn. That doesn’t bode well for international aid. Besides, the project will employ just 1,700 people and that amount only during the peak years of construction. »

Delicate subject

A leading engineering from Jordan’s water company LLC will only speak to the WWi if his anonymity remains protected on the grounds that « what I have to say is a little bit political and puts me in an awkward position ».

Once given such an assurance, however, he can hardly contain his enthusiasm for the project, lamenting the fact that Israel’s interest in the project at one point appeared to be waning on account of delays.

« The fact remains, however, that this project is a way out of our water scarcity problems, made all the more acute now because of the vast numbers of refugees coming in from Syria, » he says.

« So Jordan clear has a major interest in moving the project forward – big time. Of course it’s a delicate subject in this region – although there is now a peace treaty between Israel and Jordan what will happen to the project if tensions rise or come to be strained? But it remains my firm believe that the advantages far outweigh the disadvantages, not least because of escalating demand for water triggered off by political instability in neighbouring countries. It was frustrating to know that there is a solution to hand but that it took so long for the international machinery to creak into action. But now, finally, we are on our way. »

The water surface of the Dead Sea has shrunk dramatically – from 950 km2 square kilometres to 637 km2. The illustration shows the sea picture in 1972 and then in 2011

The World Bank to date has held public forums in Amman and Aqaba in Jordan, Eilat and Jerusalem in Israel, and Ramallah and Jericho which come under the auspices of the Palestinian Authority. These public discourses had as their theme three major World Bank reports – a feasibility study, an environmental and social assessment and a study of alternatives. Their conclusion was unambiguous – that the project was indeed feasible from engineering, economic and environmental standpoints.

World’s largest desalination plant

Their preferred method for importing substantial quantities of water from the Red Sea is to build a pumping station near Aqaba – pump it up to a high point – and then let it flow via a combination of pipelines and tunnels to the area south of the Dead Sea.

And where the world’s largest desalination plant would duly be constructed with a view to transporting almost half a billion cubic meters of desalinated water to Jordan

The plant would have a capcity of 320 million m3/year at start up, rising to 850 m3/year by 2060. It would require 247 MW of power in 2020 and 556 MW in 2060. The post-desalination high-salinity water would be piped to the Dead Sea with a view to halting, and eventually reversing, its shrinkage. Furthermore a hydroelectric plant would be built, supplying electricity to Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

Dr. Alex McPhail, who heads up the World Bank’s Red Sea-Dead Sea study programme as task team leader, highlights the fact that the assessment, led by the international consultancy Environmental Resources Management indicates that « all potential major environmental and social impacts can be mitigated to acceptable levels ».

Mixing seawater and algae

The bank has acknowledged, however, that the environmental impact in relation to the mixing of different waters from different seas remains unclear and untested, with the distinct possibility that algae could start growing in the Dead Sea.

Dr Joseph Lati of the Dead Sea Works industry, one of the world’s leading potash fertiliser producers, carried out a range of independent experiments to explore the effects of mixing. The results were not particularly promising.

« What we found were crystals of gypsum floating on the brine in small containers with 70% Dead Sea water mixing with 30% Red Sea water.

« It’s a blooming of red coloured bacteria. Of course depending on the percentage mix there will be various degrees of blooming algae. So I would advise extreme caution in this project unless and until the full effects are known. »

Full article on waterworld.com

[:]