BGU et Technion (Israël) : des coraux imprimés en bioplastique 3D fournissent un habitat apprécié des espèces

[:fr]

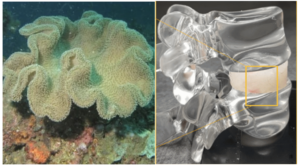

Afin de lutter contre la dégradation et le pillage des récifs coralliens dans le monde, des chercheurs de l’université Ben Gourion du Néguev et du Technion en Israël ont mis au point divers coraux imprimés en 3D susceptibles de devenir de nouveaux habitats. Dans certains cas, les poissons les préféraient aux coraux naturels. Les récifs coralliens à travers le monde connaissent un processus continu de dégradation en raison du changement climatique, de causes naturelles et de l’activité humaine, en particulier de la récolte de coraux pour aquariums.

Selon le Pr Tarazi, un nouveau concept, Design centré sur la nature (Nature-Centered Design), résume cette méthode. L’étude s’est concentrée sur la recherche de moyens de créer des coraux artificiels en bioplastique. Ils ont expérimenté différents matériaux, couleurs, tailles et formes, issus d’un modèle de corail naturel numérisé.

Bien que d’autres projets de remplacement de récifs soient en cours dans le monde entier, notamment le récif Tamar dans le golfe d’Eilat par des chercheurs de la BGU, cette initiative est la première à se concentrer sur la reproduction précise de coraux simulant la structure et la fonctionnalité de coraux naturels vivants. Ces attributs incluent l’écoulement de l’eau autour des structures coralliennes, des tailles spécifiques qui correspondent à la diversité des espèces de poissons et à la proximité des aliments (plancton).

Cette étude a été menée par l’équipe de l’université Ben Gourion du Néguev dirigée par le Pr Nadav Shashar du programme de biologie marine et de biotechnologie du BGU et le laboratoire de design-technologie dirigé par le Pr Ezri Tarazi au Technion. Les chercheurs ont utilisé des outils de conception 3D pour numériser des colonies de coraux naturels, puis manipuler les balayages de manière structurelle et spatiale pour imprimer ceux-ci artificiels. Ils ont travaillé sur différents matériaux et sur diverses imprimantes pour réaliser les modèles 3D. En fin de compte, ils ont installé quatre différentes formes de coraux imprimés dans différentes couleurs.

L’objectif était d’examiner ce qui caractérise un «bon foyer» et quel est le dessin préféré du poisson. Après l’impression 3D, les abris ont été installés sur un récif situé sur la côte nord-est de la mer Rouge, près de l’Institut interuniversitaire de la marine. Sciences à Eilat, puis les biologistes marins de Nadav Shashar ont parcouru plusieurs mois les sites de recherche et ont suivi la colonisation des modèles par des poissons naturels, non seulement les coraux imprimés en 3D, mais ils préféraient des motifs et des couleurs aux coraux vivants naturels.

« Nous avons été surpris de découvrir que la couleur importait. Les humains ne tiennent pas compte des couleurs extérieures d’une maison lorsqu’ils décident d’en acheter une, peut-être parce qu’ils peuvent la repeindre. Les poissons, en revanche, ont indiqué que la couleur de leur nouvelle maison potentielle était un facteur décisif. Les espèces de poissons qui peuvent voir les couleurs ont montré une nette préférence pour les abris colorés par rapport aux abris ternes », a déclaré le Pr Shashar.

Le Pr Shashar affirme que les observations et les interventions du concepteur ont été importantes pendant le processus de validation du concept. En comprenant le processus d’impression 3D et les matériaux utilisés, les concepteurs pourraient rapidement trouver des solutions aux problèmes survenus au cours du processus.

Dans une prochaine étape, les chercheurs essaieront de concevoir de grandes unités de récifs plutôt que des coraux simples. «Nous voulons comprendre pourquoi certaines structures fonctionnent mieux que d’autres. Notre approche met en évidence le potentiel de résolution des problèmes environnementaux par le biais de la conception. À l’aide d’outils et de méthodes de conception numériques, nous pouvons aider l’effort mondial à trouver de meilleures pratiques futures. protéger et restaurer les récifs coralliens qui sont rapidement détruits », a déclaré Nadav Shashar.

« Aucune discipline à elle seule ne peut relever ces défis. Il existe un besoin évident de collaboration interdisciplinaire. Nous avons prouvé qu’inclure des designers pour résoudre des problèmes biologiques urgents est bénéfique et peut servir de modèle pour l’intégration de la pensée conceptuelle à traiter des questions biologiques et préserver la nature », a conclu Le Pr Shashar.

Publication dans The Design Journal, mai 2019

Traduction/adaptation par Esther Amar pour Israël Science Info

[:en]

To combat the abuse and degradation of the world’s coral reefs, researchers at BGU and the Technion Institute of Technology have developed various 3D printed corals that could become new habitats. In some instances, the fish actually preferred them to natural corals. Coral reefs worldwide are experiencing a continuous process of decay as a result of climate change, natural causes and human activity, particularly coral harvesting for aquariums.

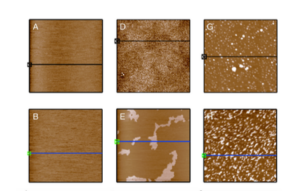

The research, published in The Design Journal, focused on finding ways to create artificial corals made of bioplastics. They experimented with different materials, colors, sizes, and forms, stemming from a scanned natural coral model.

While other reef replacement projects are underway worldwide, including the Tamar Reef in the Gulf of Eilat by BGU researchers, this initiative is the first to focus on accurately reproducing corals that simulate the structure and functionality of natural living corals. These attributes include water flow around the coral structures, specific sizes that fit the diversity of fish species and proximity to food (plankton).

The study is part of a collaboration between the BGU team led by Prof. Nadav Shashar of BGU’s Marine Biology and Biotechnology Program and the Design-Tech Lab headed by Prof. Ezri Tarazi at the Technion.

In the study, researchers used 3D design tools to scan natural coral colonies, then structurally and spatially manipulate the scans to print the artificial ones. The researchers worked through a number of different materials and a variety of printers to achieve the 3D models. Ultimately, they installed four different forms of printed corals in several colors.

The goal was to examine what makes a “good home » and which designs the fish preferred. After the shelters were 3D printed, they were installed on a reef at the northeastern coast of the Red Sea, and near the Inter-University Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat. Then Shashar’s marine biologists continuously dove the research sites over several months and tracked colonization of the models by naturally occurring fishes. Not only did the fish readily accept the 3D printed corals, but they preferred some designs and colors over natural live corals.

“We were surprised to discover that color mattered, » Prof. Shashar says. “Humans don’t take into account the outside colors of a house when deciding to buy one, perhaps because they can repaint it. Fish, on the other hand, indicated that the color of their potential new home was a make or break factor. Fish species that can see colors showed a clear preference for colored shelters over dull ones. »

Prof. Shashar says that designer’s observations and interventions were important during the concept validation process. By understanding the process of 3D printing and the materials used, the designers could quickly come up with solutions to the problems that arose during the process.

In their next stage of study, the researchers are seeking to design large reef units instead of single corals. “We want to understand what makes some structures work better than others, » says Shashar. “Our approach highlights the potential of tackling environmental challenges through design. Using digital design tools and methods, we can help the global effort to find better future practices to protect and restore coral reefs that are rapidly being annihilated. »

A new concept, “Nature-Centered Design, » according to Prof. Tarazi, encapsulates their approach to these colossal challenges.

“No discipline alone can address these challenges, » Shashar says. “There is a clear need for cross discipline collaboration. “We proved that the incorporation of designers in addressing urgent biological issues is beneficial and can serve as a model for incorporating design thinking to address biological questions and sustaining nature. »

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=48g5LC5VLo8[:]