Big data et biodiversité : la BGU (Israël), Oxford et Birmingham montrent une mine d'informations sur Wikipedia

[:fr]

Une équipe internationale de chercheurs de l’Université d’Oxford, de l’Université de Birmingham et de l’Université Ben Gourion du Néguev en Israël a constaté que la manière dont les internautes utilisent le web est étroitement liée aux schémas et rythmes du monde naturel. Cette découverte inattendue pourrait induire de nouveaux modes de surveillance de l’évolution de la biodiversité sur la planète. Elle montre aussi à quel niveau les individus s’inquiètent pour la nature, quelles espèces et quelles zones pourraient le mieux être protégées.

« Nous vivons à une époque de dégradation des écosystèmes naturels et d’effondrement de la biodiversité. De nouveaux outils et approches sont nécessaires pour faire face à ces défis gigantesques », a déclaré le Dr Uri Roll, maître de conférences à la BGU.

« Ce domaine de recherche en plein essor, la culturomique*, vise à comprendre l’interaction homme-nature telle qu’elle se manifeste dans de vastes référentiels numériques, Ceci est fait dans le but de mieux comprendre comment les gens interagissent avec la nature et d’utiliser ces informations pour permettre des mesures de conservation plus rationnelles et efficaces », ajoute le Dr Uri Roll.

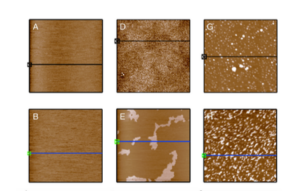

L’équipe a utilisé les pages Wikipedia et les données eBird pour étudier le comportement des internautes qui s’intéressent aux plantes et aux animaux, selon les saisons. Ils ont rassemblé une masse de données de 2,33 milliards de pages vues sur près de trois ans, pour 31 715 espèces réparties, dans 245 publications Wikipedia.

Ces modèles suggèrent que le comportement en ligne des personnes correspond au rythme de la nature. Ils ont constaté que les saisons influent beaucoup sur les visites des pages Wikipedia, pour de nombreuses espèces de plantes et d’animaux. Plus du quart des visiteurs ont manifesté un intérêt saisonnier.

Les chercheurs pensent qu’il serait possible de mesurer les changements, la rareté ou l’abondance d’espèces en vérifiant l’activité Internet qui les concerne.

Les pages pour les plantes à fleurs suscitent des requêtes saisonnières plus fortes que celles des conifères, qui n’ont pas de saison de floraison. Les pages consacrées aux insectes et aux oiseaux sont plus saisonnières que celles de nombreux mammifères.

De plus, les chercheurs ont identifié des réactions saisonnières aux événements culturels. Les pages vues sur le dindon sauvage en anglais, par exemple, ont montré des pics annuels répétés autour de Thanksgiving et les dates de chasse printanière aux États-Unis. La Shark Week* a également suscité un regain d’intérêt pour les pages sur les requins.

«Les gens sont de plus en plus déconnectés de la nature. Nous ne nous attendions pas vraiment à ce que leur activité en ligne réponde aux caractéristiques de la nature. Que l’activité en ligne soit fortement corrélée avec des phénomènes naturels suggère que les gens s’intéressent au monde qui les entoure. C’est très enthousiasmant », ajoute John Mittermeier, auteur principal et doctorant à l’Université d’Oxford.

L’équipe estime qu’il est très possible d’appliquer ces méthodes aux politiques et actions de protection de la nature, telles que la sélection d’espèces vedettes ou de zones emblématiques. Le fait de pouvoir identifier un pic saisonnier d’intérêt pour une espèce particulière pourrait aider une ONG à décider quand et comment lancer une campagne de financement particulière.

Traduit et adapté par Esther Amar pour Israël Science Info

Publication dans PLoS Biology, 5 mars 2019

* La culturomique est une nouvelle discipline qui étudie, à l’aide d’ordinateurs, la culture humaine en explorant les écrits, les séquences de mots produits par nos sociétés

* Pendant une semaine complète la chaîne Discovery diffuse uniquement des documentaires sur les requins

[:en]

An international team of researchers from The University of Oxford, the University of Birmingham and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev have found that the way in which people use the internet is very closely tied to patterns and rhythms in the natural world. This surprise finding suggests new ways to monitor changes in the world’s biodiversity. It also reveals new ways to see how much people care about nature, and which species and areas might be the most effective targets for conservation.

The team used Wikipedia pageviews records and eBird data to investigate how people’s online interest in plants and animals follows seasonal patterns. They assembled a massive dataset of 2.33 billion pageviews spanning nearly three years for 31,715 species across 245 Wikipedia language editions.

The researchers found seasonal trends to be widespread in Wikipedia interest for many species of plants and animals. More than a quarter of the species in their dataset showed seasonal interest.

For these seasonal species, the researchers found the amount and timing of internet activity is a very accurate measure of when and how the species is present in the world outside the window. The team thinks it might be possible to measure changes in the presence and abundance of species simply by seeing how much internet activity there is about them.

By taking a deep dive into the seasonal patterns, the researchers found several interesting trends. Often, seasonal interest in Wikipedia pages reflect seasonal patterns in the species themselves.

For example, pages for flowering plants tended to have stronger seasonal trends than those for coniferous trees, which don’t have an obvious flowering season. Likewise, pages for insects and birds tended to be more seasonal than those for many mammals.

Different language editions of Wikipedia show different seasonal patterns too: Wikipedia in languages mostly spoken at higher latitudes (Finnish or Norwegian for example) had more seasonal interest in species than Wikipedia editions in languages mostly spoken at lower latitudes, such as Thai or Indonesian.

In addition to correlating seasonal patterns in online interest with patterns in nature, the researchers also identified instances were seasonal patterns responded to cultural events. Page views for the wild turkey in English, for example, showed repeated annual spikes around Thanksgiving and the dates of the spring hunting season in the United States. Shark Week also caused a spike in interest.

Together these patterns suggest that people’s online behavior can respond to phenomena in the natural world.

« This work is part of a growing field of research named ‘conservation culturomics’ which aims to elucidate patterns of human-nature interactions as these are manifested in large digital repositories, » says BGU’S Dr. Uri Roll, a senior lecturer at the Mitrani Department for Desert Ecologyat the University’s Sede Boqer campus. « This is done in order to both better understand how people interact with nature and use this information to enable more sound and efficient conservation measures

« We live in an age of disintegrating natural ecosystems and biodiversity collapse. Novel tools and approaches are needed to tackle these gargantuan challenges, » Dr. Roll says.

“People are often becoming increasingly detached from the natural world and as a result we didn’t really expect their activity online to respond to patterns in the nature,” adds lead author and University of Oxford doctoral candidate John Mittermeier. “To see that online activity often correlates strongly with natural phenomena seems to suggest that people are paying attention to the world around them. From a conservation perspective, that is really exciting.”

The research team feel that there is a lot of potential to apply these methods to conservation policy and actions, such as selecting flagship species or iconic areas. Being able to identify a seasonal peak in interest in a particular species, for example, could help an organization decide when and how to launch a particular fundraising campaign.

Published in PLoS Biology, March 5th, 2019

[:]