IDC d'Herzliya, Weizmann et Université de Tel Aviv (Israël) : le berceau des ouragans montré dès 2015

[:fr]Katrina en 2005, Sandy en 2012, Irma en 2017. Tous ces noms évoquent les conséquences désastreuses de ces ouragans sur les États-Unis et ses habitants. Pourtant, des chercheurs israéliens de l’Université de Tel Aviv, de l’Institut Weizmann et de l’IDC d’Herzliya, le Pr Colin Price, la doctorante Naama Reicher et le Pr Yoav Yair, avaient publié une étude en 2015 dans la revue Geophysical Research Letters qui affichait déjà un lien entre ces différentes catastrophes naturelles, un lien qui aurait pu prévenir Irma et peut-être éviter le pire : leur lieu d’origine.

Etude complète sur ce lien

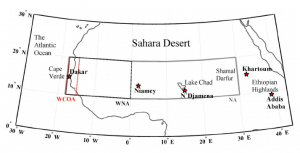

La côte ouest-africaine et plus précisément les îles du Cap-Vert sont le siège de nombreuses perturbations climatiques, les ondes tropicales. Après de nombreuses recherches, les scientifiques se sont rendu compte que ces perturbations pouvaient créer en quelques semaines d’intenses ouragans aux conséquences redoutables. Colin Price, chercheur à l’université de Tel-Aviv affirme que « près de 85 % des ouragans affectant les États-Unis, mais aussi le Canada, sont nés dans cette zone à l’ouest de la côte africaines« . Plus la surface recouverte par ces perturbations est importante, plus leurs chances de se développer en ouragans sont grandes !

Ces troubles climatiques semblent se créer par la rencontre de l’air chaud saharien avec l’air humide et plus froid du Golf de Guinée. Ce conflit de température entraîne de fortes perturbations se déplaçant jusqu’aux Îles du Cap-Vert, où se crée une mer tumultueuse de nuages plus ou moins importante, et dont la superficie pourrait prédire la création d’ouragans. En effet, ces courants d’air tropicaux rentrent par la suite en contact avec les courants d’eau chaude issus de l’océan Atlantique pour devenir encore plus violents. À une certaine vitesse, ils se transforment en ouragans plus ou moins intenses classables en différentes catégories.

L’ouragan Irma, de catégorie 5 et dont le cyclone dévastateur a atteint une vitesse de 295 km/h, fut tout d’abord diagnostiqué à la fin du mois d’août comme une simple perturbation. Perturbation qui avait 10 % de chances de se transformer en catastrophe climatique ! Malheureusement, la température exceptionnelle de l’océan Atlantique à la même période (de 2 °C supérieure à la normale) fut suffisante pour donner l’énergie nécessaire à ce phénomène climatique pour devenir alors un des cyclones les plus intenses jamais observés à ce jour.

Les découvertes météorologiques continuent et l’étude intensifiée de ce phénomène ouvre un espoir pour les scientifiques qui espèrent un jour pouvoir prédire ces catastrophes climatiques.

[:en]

Research has shown that most of the monster storms that hit the US and Canada start out as a distinct weather pattern in the atmosphere over western Africa, specifically a spot off the coast of the African Cape Verde islands.

In fact, a 2015 study published in Geophysical Research Letters showed that by closely watching these tropical disturbances off the coast of western Africa, researchers could better predict which of them would turn into serious hurricanes a few weeks later.

From L. to R.: Pr Colin Price, Naama Reicher, Pr Yoav Yair

From L. to R.: Pr Colin Price, Naama Reicher, Pr Yoav Yair

« 85 percent of the most intense hurricanes affecting the US and Canada start off as disturbances in the atmosphere over western Africa, » said lead researcher Colin Price from Tel Aviv University in Israel at the time.

« We found that the larger the area covered by the disturbances, the higher the chance they would develop into hurricanes only one to two weeks later. »

Interestingly, these hurricanes are directly linked to one of the driest places on Earth – the Sahara desert.

The interaction between the hot dry air of the Sahara and the cooler, more humid air from the Gulf of Guinea to its South forms what’s known as the African easterly jet, which blows from east to west across Africa.

Within this jet, atmospheric disturbances or bands of thunderstorm activity known as tropical waves can form. As they blow off the west coast of Africa past Cape Verde, the 2015 study showed that the amount of cloud coverage at that point can predict whether or not these tropical waves will become hurricanes a week or two later.

How does that happen? Tropical waves interact with the warm equatorial water of the Atlantic as they head west, triggering columns of warm moist air to rise from the ocean.

That provides two of the three ingredients required for tropical storms to turn into full-blown hurricanes: moist air; Earth’s rotation; and warm ocean temperatures. When the swirling winds reach speeds of 74 mph (119 km/h), the storm is classified as a Category 1 hurricane.

Irma was first spotted as a tropical disturbance off the Cape Verde Islands in late August, before becoming a hurricane over the Atlantic as it made its way towards the Caribbean and US.

According to Price, only 10 percent of the 60 disturbances originating in Africa every year turn into hurricanes – but the ones that do have the opportunity to gather energy as they cross the Atlantic, which makes them so powerful that they’re more likely to hit the US and even Canada.

« Not all hurricanes that form in the Atlantic originate near Cape Verde, but this has been the case for most of the major hurricanes that have impacted the continental United States, » writes the NOAA.

Researchers around the world are now working on better being able to predict which of these disturbances is worth watching and preparing for.

« If we can predict a hurricane one or two weeks in advance — the entire lifespan of a hurricane — imagine how much better prepared cities and towns can be to meet these phenomena head on, » said Price.

[:]