Tel Aviv University researchers discover chemical found in most sunscreen lotions poses an existential threat to young corals. The daily use of sunscreen bearing an SPF of 15 or higher is widely acknowledged as essential to skin cancer prevention, not to mention skin damage associated with aging. Though this sunscreen may be very good for us, it may be very bad for the environment, a new Tel Aviv University study finds.

New research finds that a common chemical in sunscreen lotions and other cosmetic products poses an existential threat — even in miniscule concentrations — to the planet’s corals and coral reefs. “The chemical, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), is found in more than 3,500 sunscreen products worldwide. It pollutes coral reefs via swimmers who wear sunscreen or wastewater discharges from municipal sewage outfalls and coastal septic systems,” said Dr. Omri Bronstein of TAU’s Department of Zoology, one of the principal researchers.

The study was conducted by a team of marine scientists from TAU, including Prof. Yossi Loya, also of the Department of Zoology, the Haereticus Environmental Laboratory in Virginia, the National Aquarium (US), the US. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, and other labs in the US.

The researchers hope their study will draw awareness of the dangers posed by sunscreen to the marine environment and promote the alternative use of sun-protective swimwear.

A deadly day at the beach

A person spending the day at the beach might use between two to four ounces of sunblock if reapplied every two hours after swimming, towelling off, or sweating a significant amount. Multiply this by the number of swimmers in the water, and a serious risk to the environment emerges.

“Oxybenzone pollution predominantly occurs in swimming areas, but it also occurs on reefs 5-20 miles from the coastline as a result of submarine freshwater seeps that can be contaminated with sewage,” said Dr. Bronstein, who conducted exposure experiments on coral embryos at the Inter University Institute in Eilat together with Dr. Craig Downs of the Heretics Environmental Laboratories. “The chemical is highly toxic to juvenile corals. We found four major forms of toxicity associated with exposure of baby corals to this chemical.”

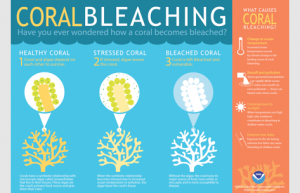

Forms of toxicity include coral bleaching, a phenomenon associated with high sea-surface temperature events like El Niño — and with global mass mortalities of coral reefs. The researchers found oxybenzone made the corals more susceptible to this bleaching at lower temperatures, rendering them less resilient to climate change. They also found that oxybenzone damaged the DNA of the corals, neutering their ability to reproduce and setting off a widespread decline in coral populations.

The study also pointed to oxybenzone as an “endocrine disruptor,” causing young coral to encase itself in its own skeleton, causing death. Lastly, the researchers saw evidence of gross deformities caused by oxybenzone — i.e., coral mouths that expand to five times their healthy, normal size.

It only takes a drop

“We found the lowest concentration to see a toxicity effect was 62 parts per trillion — equivalent to a drop of water in six and a half Olympic-sized swimming pools,” said Dr. Bronstein. The researchers found concentrations of oxybenzone in the US Virgin Islands to be 23 times higher than the minimum considered toxic to corals.

“Current concentrations of oxybenzone in these coral reef areas pose a significant ecological threat,” said Dr. Bronstein. “Although the use of sunscreen is recognized as important for protection from the harmful effects of sunlight, there are alternatives — including other chemical sunscreens, as well as wearing sun clothing on the beach and in the water.”

Publication in Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 20 oct. 2015