Weizmann, KKL, Volcani : les jeunes arbres peinent à atteindre leur maturité en raison de la sécheresse accentuée par la crise climatique

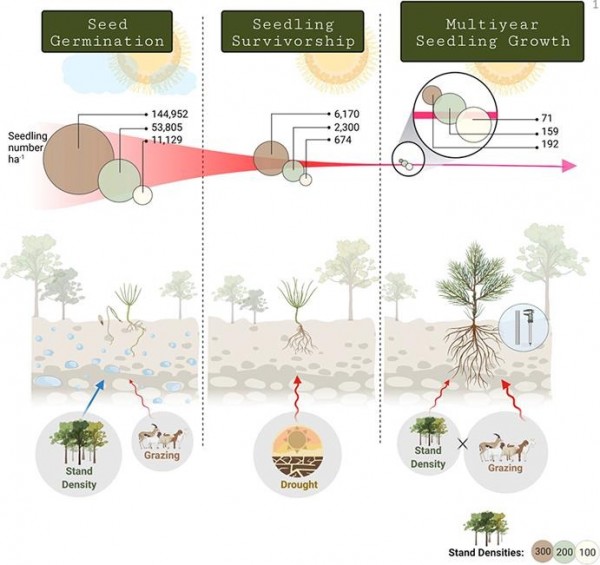

Dans les forêts, la capacité à engendrer les générations suivantes de jeunes arbres reste essentielle pour fournir des services écosystémiques et d’habitat durables pour les humains et la faune. Selon une étude israélienne, cependant, la baisse des précipitations induite par le changement climatique présente de sérieuses menaces pour la régénération naturelle des forêts, en particulier dans les forêts israéliennes. Pour que la régénération réussisse, suffisamment de germes doivent survivre pour devenir de jeunes arbres sains.

Ces processus ont été examinés par une équipe de chercheurs du Weizmann Institute of Science (dont le Pr Dan Yakir), du KKL-JNF et du Volcani Institute. Financée par le KKL-JNF et publiée dans Forest Ecology and Management, l’étude a été menée entre 2015 et 2020 dans la forêt de Yatir, la plus grande forêt plantée d’Israël (7413 acres) située dans une région semi-aride située entre les montagnes de Judée et du Néguev, en bordure de l’aire de répartition des pins (le point le plus éloigné où pousse l’espèce). Au début, les chercheurs ont observé une croissance abondante des germes au cours des mois de mars et d’avril, mais cette régénération s’est rapidement estompée. « En saison, nous avons vu une germination très importante et massive, de sorte que la forêt semblait pousser normalement et bien », explique Ella Pozner, étudiante diplômée au Département des sciences végétales et environnementales de l’Institut Weizmann des sciences et l’une des chercheuses de l’étude.

Cependant, la tendance s’est rapidement inversée et seule une fraction des germes – au plus 10% – a survécu à l’été jusqu’en septembre. Au cours des 6 années d’étude, seules quelques pousses ont réussi à devenir de jeunes arbres ; un maximum de 20 arbres en moyenne par dunam par an. A titre de comparaison, la forêt de Malachim-Shachariya, près de Kiryat Gat, abrite en moyenne plusieurs centaines de jeunes arbres par dunam et par an.

Régénération compromise

Selon les chercheurs, les pousses de la forêt de Yatir ont eu du mal à atteindre leur maturité principalement en raison du manque de précipitations. Cela était particulièrement visible pendant les années sèches, en particulier entre 2017 et 2019, lorsque le taux de survie estivale des pousses est tombé à près de zéro. En outre, l’étude a révélé que le pâturage des animaux, au cours duquel la faune piétine et mange les pousses, et la forte densité d’arbres, qui réduit la pénétration de la lumière du soleil et la quantité d’eau disponible dans le sol, nuisent également à la capacité de régénération des forêts. « Si vous venez dans la forêt de Yatir après la pluie, tout sera vert et beau, mais vous ne verrez pas un champ d’enfants » dans la forêt – de jeunes arbres qui remplaceront un jour les arbres plus âgés et mourants », explique le Dr. Tamir Klein de l’Institut Weizmann des sciences végétales et environnementales. Selon lui, les quelques arbres qui ont réussi à pousser au-delà de leurs stades de germination sont très courts et ressemblent à des arbustes plutôt qu’à de grands arbres. Tamir Klein met en garde contre la possibilité que dans une trentaine d’années la forêt n’existe plus.

Tout tourne autour de la sécheresse

L’échec de la régénération est un problème que connaissent de nombreuses forêts, en particulier celles situées en bordure des aires de répartition. Comme le révèle l’étude, la régénération de vastes zones de la forêt de Yatir en Israël est déjà perturbée, en particulier pendant les années de sécheresse intense. Dans ces zones, certaines espèces d’arbres courent le risque de disparaître, c’est-à-dire la disparition complète d’une espèce dans une zone ou une région spécifique. « La crise climatique entraîne de nombreux changements dans le monde entier, ainsi qu’une augmentation des températures mondiales et la fréquence des années de sécheresse et des événements climatiques extrêmes », déclare Ella Pozner. « En fin de compte, même les forêts considérées comme plus humides et conservant des niveaux d’humidité plus élevés rencontreront et lutteront contre des conditions de sécheresse ». Au cours de la dernière décennie, de nombreuses études ont été menées dans le monde entier sur la capacité de régénération des forêts à l’ère de la crise climatique moderne.

Des difficultés de régénération de diverses espèces ont été constatées chez les espèces de pins et de sapins des forêts des Rocheuses aux États-Unis, dont la végétation souffre également des incendies de forêt nés de la sécheresse. Des changements spatiaux et des changements de composition dans les populations d’arbres ont également été observés dans les forêts boréales (forêts de conifères et de feuillus très froides qui s’étendent sur des zones de haute altitude en Asie et en Amérique du Nord) et dans les régions tropicales humides d’Asie de l’Est. D’autres études portent spécifiquement sur les mécanismes d’adaptation qui se développent chez les arbres au niveau cellulaire leur permettant de se régénérer plus facilement et de faire face aux changements climatiques locaux. De tels mécanismes ont été observés dans des forêts en Grèce, au Brésil et ailleurs.

Quelles réponses ?

Alors, que peut-on faire pour améliorer la situation et aider les forêts à se régénérer, malgré les conditions difficiles ? Selon Tamir Klein, il existe de nombreux outils d’interface forestière qui peuvent être utilisés pour aider à la régénération, tels que :

placer une gaine de protection en plastique autour des résineux au cours de leur première année qui les protège des vents violents et des animaux qui paissent,

établir des barrages bas près de l’eau de pluie du lac,

construire des barrages bas près des arbres vers l’eau de pluie du lac,

la sélection d’arbres résistants à la sécheresse pour les futures plantations

l’éclaircissage des arbres pour augmenter la quantité d’eau disponible dans les sols ainsi que la lumière du soleil qui pénètre à travers les couverts forestiers.

Avec ces mesures et des recherches supplémentaires, les pousses de nouvelle génération pourraient mieux résister aux conditions estivales difficiles et préserver certaines des forêts les plus précieuses et les plus appréciées au monde.

Publication in Science direct Februar 2022

Auteur Orit Eran pour Zavit June 15, 2022

Traduit et adapté par Esther Amar pour Israël Science Info