Université de Tel Aviv, Sheba (Israël), MIT (USA) : désactiver des gènes pour stopper la progression du cancer du sein !

[:fr]Une étude sur des souris de laboratoire menée par le Dr Noam Shomron de l’Ecole de médecine de l’Université de Tel-Aviv, en collaboration avec un laboratoire du MIT (USA), a réussi à stopper complétement la production des métastases engendrées par les tumeurs cancéreuses du sein vers d’autres organes du corps, grâce à des micro ARN qui désactivent les gènes permettant aux cellules malignes de changer de forme pour pénétrer dans la circulation sanguine. Selon les chercheurs, ce traitement a de grandes chances d’être efficace également chez les femmes atteintes du cancer du sein en raison de la grande similitude entre les gènes examinés dans les tumeurs des souris et celles des femmes.

Le Dr Natalie Artzi du MIT, le Dr Daphna Weisglass-Volkov et la doctorante Avital Gilam du laboratoire du Dr Shomron ont participé à cette étude.

« Le cancer du sein est le plus meurtrier des cancers chez les femmes ; une femme sur huit dans le monde connaitra la maladie durant sa vie », déclare le D. Shomron. « Les chercheurs du monde entier investissent d’énormes efforts dans le développement de traitements sophistiqués, mais le succès reste encore très limité : la survie des malades 5 ans après le diagnostic n’a augmenté que de 3% au cours des 20 dernières années, et les chances de guérison diminuent considérablement après le développement des métastases. Notre recherche apporte une nouvelle approche de la question: au lieu de se concentrer sur le traitement de la tumeur primaire elle-même, nous avons décidé de mettre l’accent sur la formation des métastases. Si nous parvenons à faire en sorte que le cancer reste local, nous pourrons le traiter beaucoup plus efficacement ».

Les chercheurs ont donc cherché comment stopper le mécanisme par lequel les cellules cancéreuses se déplacent afin qu’elles ne puissent pas migrer de la tumeur primaire vers les organes vitaux du corps. « Au moment de la migration, la cellule se rétrécit pour s’infiltrer dans la circulation sanguine », explique le Dr. Shomron. « Lorsqu’elle atteint sa destination, elle change de forme une fois de plus afin de sortir des vaisseaux sanguins pour s’enraciner dans le nouvel organe. Nous avons dévoilé le mécanisme génétique qui génère ces changements des cellules cancéreuses et cherché un moyen de le neutraliser ».

Les chercheurs ont tout d’abord tenté d’identifier les gènes spécifiques impliqués dans la modification de la forme de la cellule cancéreuse, au moyen d’outils de pointe dans le domaine de la bio-informatique. « Nous avons utilisé d’énormes bases de données en Israël et à l’étranger, et avons croisé quatre types de données : les mutations de l’ADN qui caractérisent le cancer du sein, un sous-ensemble de gènes responsables de la modification de la forme de la cellule, des gènes qui présentent des domaines de liaisons avec des microARN régulateurs (capables d’extinction de l’expression d’un gène) et des données cliniques sur les mutations effectivement enregistrées chez les patientes atteintes du cancer du sein, obtenues auprès du Prof. Eitan Friedman du Centre médical Sheba à Tel Hashomer ».

Le recoupement des données a permis d’identifier un gène spécifique appartenant aux quatre groupes. Les chercheurs ont alors fait l’hypothèse que la désactivation de ce gène permettrait de diminuer considérablement la capacité du cancer de se déplacer et de produire des métastases. Pour la vérifier, ils ont produit deux types de molécules de microARN, naturellement responsables du contrôle du gène concerné et ont désactivé celui-ci. Ils ont ensuite testé la nouvelle thérapie sur des souris de laboratoire.

« Trois semaines après le début du traitement, les souris traitées par les micro-ARN étaient presque totalement exemptes de tumeurs secondaires » rapporte le chercheur. « Cela signifie que nous avons réussi à arrêter la propagation du cancer. Nous pensons que le nouveau traitement que nous avons mis au point, qui s’est montré efficace chez des souris de laboratoire, possède le même potentiel chez les femmes atteintes du cancer du sein en raison de la grande similitude entre les gènes examinés à la fois chez les souris et chez les femmes dans les tumeurs ».

Le Dr Shomron et son équipe vérifient à présent où et comment agit le traitement : le micro-ARN s’enroule-t-il autour de la tumeur primaire, se lie-t-il aux cibles en empêchant l’épanchement des cellules cancéreuses dans la circulation sanguine ? agit-il sur les cellules malignes pendant leur circulation dans le sang ? est-il efficace également pour le traitement des métastases déjà installées dans le nouvel organe? Les chercheurs espèrent que les réponses à ces questions pourront conduire vers le début d’un processus de développement de médicaments innovants et efficaces pour soigner le cancer du sein.

Auteur Sivan Cohen-Wiesenfeld, PhD, Rédactrice en chef du site des Amis français et des Amis francophones de l’Université de Tel-Aviv

Publication dans Nature Communications, le 19/09/16[:en]A new Tel Aviv University study finds that combining genetic therapy with chemotherapy delivered to a primary tumor site is extremely effective in preventing breast cancer metastasis.

The research was led by Dr. Noam Shomron of TAU’s Sackler School of Medicine in collaboration with Dr. Natalie Artzi of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and conducted by Dr. Shomron’s students Avital Gilam and Dr. Daphna Weissglas and Dr. Artzi’s student Dr. Joao Conde. Data on human genetics were provided by Prof. Eitan Friedman of TAU’s Sackler Faculty of Medicine and Chaim Sheba Medical Center.

Stopping cancer at the turning point

One in eight women worldwide are diagnosed with breast cancer during their lifetimes. Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in women. The chance that a woman will die from breast cancer is about 1 in 36. Early detection, while increasingly common, is not sufficient to preventing metastasis, the lethal movement of cancerous cells from a primary tumor site to colonies in vital organs. About 80 percent of women with metastatic cancer die from the disease within just five years of being diagnosed.

« The situation is bleak. Death rates from breast cancer remain high and relatively unchanged despite advances in medicine and technology, » said Dr. Shomron. « We wanted to find a way to stop metastasis from happening altogether. It’s the turning point, where survival rates drop exponentially.

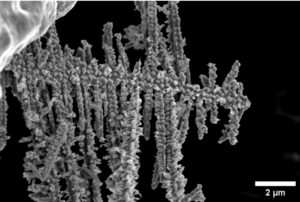

« Our mission was to block a cancer cell’s ability to change shape and move. Cancer cells alter their cytoskeleton structure in order to squeeze past other cells, enter blood vessels and ride along to their next stop: the lungs, the brain or other vital organs. We chose microRNAs as our naturally-occurring therapy, because they are master regulators of gene expression. »

Database, drugs and delivery

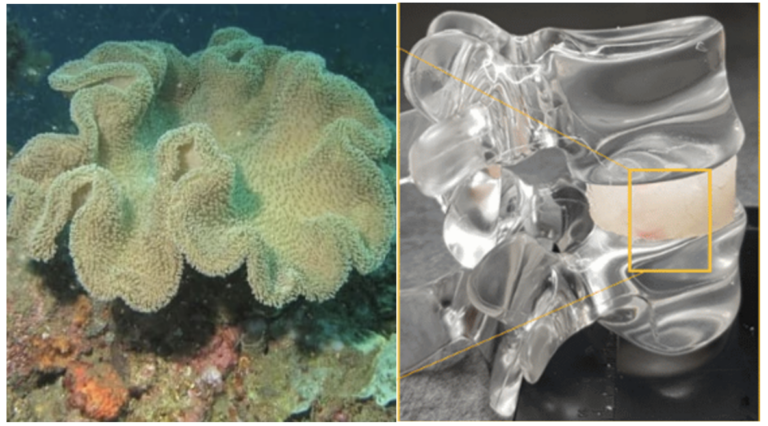

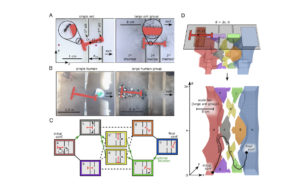

The researchers based their approach on the « 3Ds » — database, drugs and delivery. The team began by exploring bioinformatics databases to investigate the span of mutations in a tumor and identify precisely which ones to target. The scientists then procured a naturally-occurring, RNA-based drug to control cell movement and created a safe nanovehicle with which to deliver the microRNA to the tumor site.

« We looked at mutations and polymorphisms that other researchers have ignored, » said Dr. Shomron. « Mutations in the three prime untranslated regions (UTRs) at the tail end of a gene are usually ignored because they aren’t situated within the coding region of the gene. We looked at the three UTR sites that play regulatory roles and noticed that mutations there were involved in metastasis. »

Two weeks after initiating cancer in the breasts of their mouse « patients, » the researchers injected into primary tumor sites a hydrogel that contained naturally occurring RNAs to target the movement of cancer cells from primary to secondary sites. Two days after this treatment, the primary breast tumors were excised.

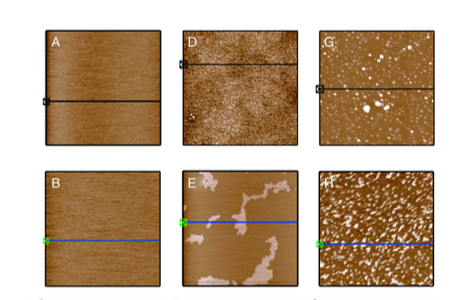

The mice were evaluated three weeks later using CT imaging, flourescent labelling, biopsies and pathology. The researchers discovered that the mice that had been treated with two different microRNAs had very few or no metastatic sites, whereas the control group — injected with random scrambled RNAs — exhibited a fatal proliferation of metastatic sites.

From mice to humans

« We realized we had stopped breast cancer metastasis in a mouse model, and that these results might be applicable to humans, » said Dr. Shomron. « There is a strong correlation between the effect on the genes in mouse cells and the effect on the genes in human cells. Our results are especially encouraging because they have been repeated several times at TAU and at MIT by independent groups. »

The researchers are continuing their study of the effects of microRNAs on tumors within different microenvironments.

Publication in Nature Communications, 19/09/16[:]