Université Ben Gourion du Négev : le Losartan, un médicament du marché peut prévenir l'épilepsie post-traumatique et empêcher son développement

[:fr]Entre 10 et 20 % des cas d’épilepsie résultent de traumatismes crâniens graves, mais le losartan, un médicament qu’on trouve sur le marché, peut empêcher cette suite tragique, et prévenir d’autres dommages au cerveau dus aux crises des patients déjà atteints d’épilepsie. Une équipe de chercheurs de l’Université Ben-Gourion du Néguev, de l’Université Berkeley (Californie), et de la faculté de médecine Charité (Allemagne) ont montré que ce médicament empêche la majorité des cas d’épilepsie post-traumatique chez un modèle de rongeur. Si des expériences indépendantes confirment cette constatation, les essais cliniques humains pourraient débuter d’ici quelques années. « C’est la première fois que le développement de l’épilepsie est stoppé, contrairement aux médicaments ordinaires qui tentent de prévenir les crises une fois que l’épilepsie s’est développée », a déclaré Alon Friedman, Professeur de physiologie et de neurobiologie et membre du Centre Zlotowski des neurosciences à l’université Ben Gourion. « Les traitements actuels, administrés depuis de nombreuses années, n’ont qu’un succès limité et comporte de nombreux effets secondaires. Aussi nous sommes très enthousiasmés par cette nouvelle approche. » L’étude a été soutenue par le programme cadre FP7 de l’Union européenne, la Fondation Israël des Sciences, la Fondation binationale des sciences États-Unis-Israël et l’Institut national des troubles et maladies neurologiques du NIH.

Publication sur http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ana.24147/abstract[:en]Between 10 and 20 percent of all cases of epilepsy result from severe head trauma, but a new drug promises to prevent this tragic aftermath, and may forestall further brain damage caused by seizures in those who already have epilepsy. A team of researchers from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, University of California, Berkeley, and Charité-University Medicine in Germany reports in the current issue of the Annals of Neurology that a hypertension drug already on the market prevents a majority of cases of post-traumatic epilepsy in a rodent model of the disease. If independent experiments now underway confirm this finding, human clinical trials could start within a few years.

« This is the first-ever approach in which epilepsy development is stopped, as opposed to common drugs that try to prevent seizures once epilepsy develops, » said Alon Friedman, Professor of Physiology and Neurobiology and a member of the Zlotowski Center for Neuroscience at BGU. « Those drugs are administered for many years, have a limited success and involve many side effects, so we are excited about the new approach. » The team, led by Alon Friedman, Daniela Kaufer, UC Berkeley associate professor of integrative biology and a member of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, and Uwe Heinemann of the Charite, provides the first explanation for how brain injury caused by a blow to the head, stroke or infection, leads to epilepsy. Based on 10 years of collaborative research, their findings point a finger at the blood-brain barrier, the tight wall of cells lining blood vessels in the brain that is breached after trauma. « This study for the first time offers a new mechanism and an existing, FDA-approved drug to potentially prevent epilepsy in patients after brain injuries and once they develop an abnormal blood-brain barrier, » said Kaufer.

The drug, losartan (Cozaar®), prevented seizures in 60 percent of the rats tested, when normally 100 percent of the rats develop seizures after this model of injury. In the 40 percent of rats that did develop seizures, they averaged about one quarter the number typical for untreated rats. The experiment showed that administration of losartan for three weeks at the time of injury was enough to prevent most cases of epilepsy in normal lab rats in the following months.

“This is a very exciting result, telling us that the drug worked to prevent the development of epilepsy and not by suppressing the symptoms,” Friedman said.

Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier

Friedman and Kaufer have been collaboratively investigating the effects of trauma on the brain for two decades. Friedman’s main interest is in the blood-brain barrier, which normally protects the brain from potentially damaging chemicals or bacteria in the blood and prevents brain chemicals from leaking into the blood stream.

He and Kaufer showed earlier that breaking down the barrier causes inflammation and the development of epilepsy. They pinned the effect to a single protein called albumin, the most common protein in blood serum.

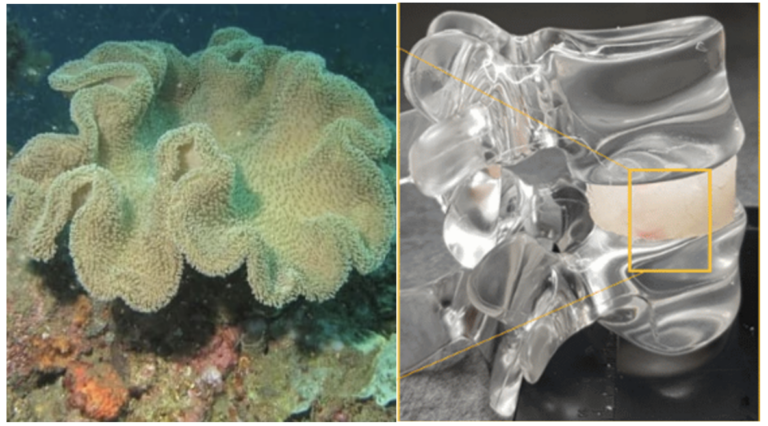

In 2009, they showed that albumin affects astrocytes, the brain’s support cells, by binding to the TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta) receptor. This initiates a cascade of steps that lead to localized inflammation, which appears to permanently alter the brain’s wiring, leading to the electrical misfiring characteristic of epilepsy. The current paper conclusively demonstrates that blocking the TGF-beta receptor with losartan stops that cascade and prevents epilepsy.

Drugs side effect proves crucial

Coauthor Guy Bar-Klein, a doctoral student at Ben-Gurion University, searched a long list of drugs before discovering losartan, which is approved to treat high blood pressure because it blocks the angiotensin II receptor 1, but which incidentally was also found to block TGF-β signaling. It worked in the rats even when delivered in their drinking water, which means that it gets into the brain through the disrupted blood-brain barrier.

In parallel, Friedman’s lab together with the Brain Imaging group at Soroka University Medical Center headed by Dr. Ilan Shelef, developed a protocol to use MRI to diagnose whether the blood brain barrier has been breached, allowing doctors to give losartan as a preventive treatment if necessary after trauma. Friedman said that the barrier may remain open for only a few weeks after injury, so the drug should be given only to those patients who need it, and for a limited period.

« Right now, if someone comes to the emergency room with traumatic brain injury, they have a 10 to 50 percent chance of developing epilepsy, and epilepsy from brain injuries tend to be unresponsive to drugs in many patients. » Friedman said. « In addition, since breakdown of the blood-brain barrier may also be associated with other complications, including bleeding and changes in cognitive functions, we are expecting that our approach will prevent complications other than epilepsy.”

The study was supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program, the Israel Science Foundation, the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health (RO1/NINDS NS066005).

Other coauthors are Luisa P. Cacheaux, a former UC Berkeley graduate student now a postdoc at the Center for Learning and Memory of the University of Texas, Austin; graduate students Lyn Kamintsky, Ofer Prager and Itai Weissberg of Ben-Gurion University; neuroscientists Uwe Heinemann and Karl Schoknecht of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin in Berlin, Germany; and graduate student Paul Cheng and postdocs Soo Young Kim and Lydia Wood of UC Berkeley’s Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute.

*Losartan prevents acquired epilepsy via TGF-β signaling suppression (Annals of Neurology, 2014) – http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ana.24147/abstract[:]