Les chercheurs des Universités de Bonn et de Jérusalem (Israël) découvrent l'interrupteur des crises d'épilepsie

[:fr]Alors que le scandale de la Dépakine* éclate, ce médicament antiépileptique commercialisé par le laboratoire Sanofi signalé comme étant l’origine de nombreux problèmes de développement du foetus chez les femmes enceintes, Esther Amar, fondatrice et directrice Israël Science Info rappelle « qu’en octobre dernier, les Universités de Bonn et de Jérusalem ont publié une étude qui pourrait faire grandement avancer la mise au point de traitements de cette maladie qui compte près de 500 000 patients en France et 100 nouveaux cas par jour« .

santeblog. Environ un patient sur 3 atteint d’épilepsie temporale, la forme d’épilepsie la plus fréquente chez l’adulte, ne répond pas aux médicaments. En découvrant un interrupteur de l’épilepsie, ces chercheurs de l’Université de Bonn identifient une cible très prometteuse pour réduire la fréquence et la sévérité des crises. Les conclusions, présentées dans la revue Nature Communications ouvrent des options thérapeutiques pour les patients atteints de formes réfractaires de la maladie.

Contrairement à l’idée généralement reçue, l’épilepsie n’est pas une affection neurologique rare. Environ une personne sur 20 connaîtra, au cours de sa vie, une crise d’épilepsie, plus ou moins sévère. Durant cette crise, les cellules nerveuses vont » s’enflammer » à une fréquence très rapide provoquant comme un court-circuit dans le cerveau et des convulsions dans le corps. Ces décharges synchrones dans le cerveau sont plus fréquentes dans le lobe temporal.

Les scientifiques de l’Université de Bonn et de l’Université hébraïque de Jérusalem (Israël) décodent, avec ces travaux, la cascade de signaux associée à la crise. Ils identifient un interrupteur dont le blocage, chez des souris modèles d’épilepsie, entraine une réduction significative de la fréquence et de la sévérité des crises. Ils utilisent également une nouvelle technologie qui leur permet d’observer la cascade moléculaire qui précède la survenue d’une crise.

Inhiber un interrupteur génétique des crises

L’hypothèse de départ est qu’avant une crise d’épilepsie, la concentration en ions de zinc libres augmente dans l’hippocampe, une zone située dans le lobe temporal. L’équipe identifie une voie de signalisation impliquée dans l’apparition du trouble épileptique. Alors que le nombre d’ions de zinc augmente avant la crise (ou après une lésion cérébrale transitoire), ces ions se regroupent en grand nombre sur un interrupteur, MTF1 (pour metal-regulatory transcription factor 1). Cet attroupement induit une forte augmentation de la quantité de canaux d’ions dans les cellules nerveuses et finalement augmente le risque de crises d’épilepsie. En inhibant » génétiquement » l’interrupteur MTF1 chez des souris modèles d’épilepsie, les chercheurs constatent que les crises se font plus rares et moins sévères. En conclusion, il s’agit de parvenir à inhiber les ions zinc ou le facteur de transcription MTF1 pour empêcher ou réduire les crises.

Pouvoir aussi prévoir la crise chez l’Homme

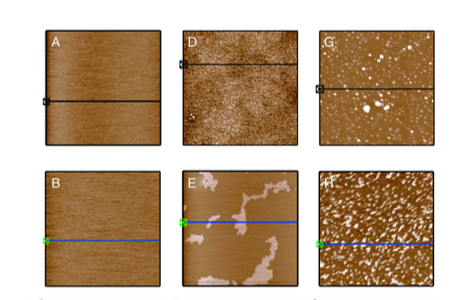

Ces travaux ont aussi été l’opportunité de développer une nouvelle méthode d’observation à l’échelle moléculaire. Ici, les chercheurs ont introduit, grâce à un virus, une fluorescence des molécules en cas de production active de canaux d’ions calcium. Les faisceaux de lumière émanant de ces molécules fluorescentes (voir visuel ci-contre) peuvent être mesurés à partir du sommet des crânes des souris. En bref, la fluorescence indique que la souris prépare une crise d’épilepsie. Une technique qui pourrait donc, être très utile, aussi, chez l’Homme.

Source : Nature Communications oct, 2015

Article mis en ligne sur santeblog par P. Bernanose, D. de publication

* C’est le Canard Enchaîné qui a dévoilé l’affaire : la Dépakine, médicament antiépileptique commercialisé par le laboratoire Sanofi, a été prescrite à plus de 10000 femmes enceintes entre 2007 et 2014, alors même que celle-ci avait été signalée comme étant l’origine de nombreux problèmes de développement. Une situation alarmante puisque 30 à 40% des enfants exposés in utero seraient l’objet de troubles du développement, et de malformations pour 11% d’entre eux. Libération en parlait en juillet. [:en]Scientists at the University of Bonn and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Israel) have decoded a central signal cascade associated with epileptic seizures. If the researchers blocked a central switch in epileptic mice, the frequency and severity of the seizures decreased. Using a novel technology, it was possible to observe the processes prior to the occurrence of epileptic seizures in living animals. The results are now being published in the journal « Nature Communications ».

Approximately one out of every 20 people in the course of his or her life suffers an epileptic attack, during which the nerve cells get out of their usual rhythm and fire in a very rapid frequency. This results in seizures. Such synchronous discharges in the brain occur most frequently in the temporal lobe. Often, a seizure disorder develops after a delay following transient brain damage – for example due to injury or inflammation. So-called ion channels are involved in the transfer of signals in the brain; these channels act like a doorman to regulate the entry of calcium ions in the nerve cells.

« It has also been known for a long time that following transient severe brain injury and prior to an initial spontaneous epileptic seizure, the concentration of free zinc ions increases in the hippocampus. But science has been puzzled about the significance of this phenomenon, » says Prof. Dr. Albert J. Becker from the Institute of Neuropathology of the University of Bonn. The hippocampus, located in the temporal lobe, is a central switching station in the brain.

MTF1 acts like a switch in the brain

The team of Prof. Becker, together with scientists from the departments of Experimental Epileptology and Neuroradiology of the University of Bonn Hospital as well as from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem (Israel), have now decoded a signaling pathway which is involved in the onset of a seizure disorder. If the number of zinc ions increases following transient severe brain damage, these ions dock in greater numbers onto a switch, the so-called metal-regulatory transcription factor 1 (MTF1). This leads to a large increase in the amount of a special calcium ion channel in the nerve cells and overall, this significantly boosts the risk of epileptic seizures.

The scientists demonstrated the fact that the transcription factor MTF1 plays a central role in this connection using an experiment on mice suffering from epilepsy. « Using a genetic method, we inhibited MTF1 in the epileptic mice and as a result, the seizures in the animals were much rarer and weaker, » says lead author Dr. Karen M.J. van Loo who is conducting research in the team working with Prof. Becker.

New technology enables observations of the living brain

The scientists used a novel method during their examinations. With the help of viruses, the researchers introduced fluorescing molecules in the brains of mice and these molecules always glowed when the production of the special calcium ion channel was activated. The beams of light emanating from the fluorescence molecules can be measured through the top of the mice’s skulls. This makes it possible to examine the processes which take place during the development of epilepsy in a living animal.

« If the fluorescence molecules glow, this indicates that the mouse is developing chronic epileptic seizures, » says the molecular biologist Prof. Dr. Susanne Schoch from the department of Neuropathology at the University of Bonn. The researchers also see a possible potential in this new technology for novel diagnostic approaches in humans.

Hope for new options for diagnosis and treatment

The scientists hope that new treatment options will open up for epilepsy patients as a result of their discovery. « About one-third of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy do not respond to medications. Our research is therefore increasingly focusing on new therapeutic options that have few side effects, » states Prof. Becker. If the zinc ions or the transcription factor MTF1 were specifically inhibited in the brain, it is possible that the development of a seizure disorder could be prevented. « However, this still needs to be demonstrated in further studies, » says Dr. Karen M.J. van Loo.

Source : Nature Communications Oct 26th, 2015

Source : Bonn University[:]