Weizmann (Israël) : les probiotiques sont-ils vraiment efficaces ?

[:fr]

La prise de probiotiques est-elle bonne pour notre flore intestinale ? Pas sûr, affirment deux nouveaux travaux scientifiques. Découverts au siècle dernier, ces micro-organismes vivants, levures ou bactéries, sont présents dans certaines boissons et compléments alimentaires, dans des céréales, mais surtout dans les produits laitiers, dans lesquels on retrouve deux espèces principales, Lactobacillus et Bifidobacterium. On leur prête une action bénéfique pour la santé, surtout pour les défenses immunitaires et le transit intestinal. L’OMS les définit comme « des bactéries ou levures qui, ingérées en quantité suffisante, améliorent la santé de l’hôte en équilibrant la flore intestinale ».

C’est d’ailleurs pour cette raison que la prise de probiotiques est recommandée pour prévenir les désordres intestinaux suite à un traitement antibiotique. Déjà décriés par le passé, les probiotiques font à nouveau l’objet de deux études menées par l’Institut Weizmann des sciences, en Israël, du centre M2dical Sourasky à Tel Aviv et du Centre Migal en Galilée et et qui contestent leur efficacité. Selon les chercheurs, les probiotiques ne seraient pas capables de s’implanter dans le microbiote intestinal et d’en modifier la composition.

25 volontaires en bonne santé

« Les gens ont apporté beaucoup de crédit aux probiotiques, alors même que la littérature à ce sujet est très controversée. Nous voulions ici déterminer si les probiotiques tels que ceux que l’on trouve en supermarché colonisent le tractus gastro-intestinal comme ils sont censés le faire, et ensuite si ces probiotiques ont un impact sur l’hôte humain », explique l’immunologiste Eran Elinav et co-auteur de l’une des deux études.

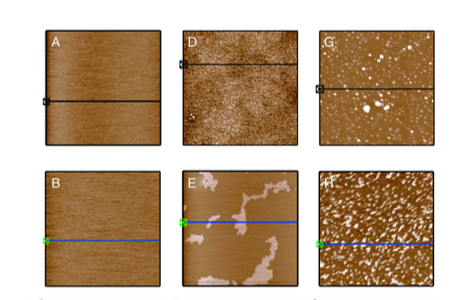

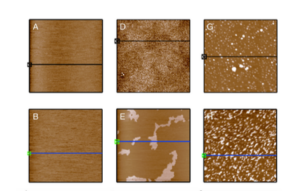

Première étude : les chercheurs ont soumis 25 volontaires en bonne santé à des endoscopies et des coloscopies pour prélever un échantillon de leur microbiote intestinal. Parmi eux, 15 ont ensuite été divisés en deux groupes : le premier a consommé des souches de 11 probiotiques, le second a reçu un placebo. Au moyen de nouveaux examens invasifs, les chercheurs ont à nouveau examiné le microbiote des sujets et se sont aperçus que les bactéries avaient colonisé avec succès les voies gastro-intestinales de certains participants. Pour d’autres, en revanche, les probiotiques ont été rejetés.

« Chez ces derniers, les bactéries déjà présentes dans le tube digestif ont formé une barrière qui a empêché la greffe des organismes étrangers », constate Eran Elinav. Selon lui, « les probiotiques ne devraient pas être donnés universellement, à l’aveugle, mais de façon ciblée et adaptée à chaque individu. C’est sur cette approche personnalisée que la recherche doit maintenant se concentrer ».

Vers une consommation personnalisée de probiotiques

Seconde étude : les chercheurs se sont intéressés à l’efficacité des probilotiques pour contrer les effets des antibiotiques. Sont-ils réellement efficace pour repeupler le microbiote intestinal qui a été éliminé par le traitement antibiotique ? Pour le savoir, ils ont administré à 21 volontaires des antibiotiques. Ces derniers ont ensuite été répartis au hasard en trois groupes. Le premier était un groupe de surveillance qui laissait son microbiote se rétablir tout seul. Le deuxième groupe a reçu les mêmes probiotiques génériques que ceux utilisés dans la première étude.

Le troisième groupe a reçu une greffe autologue de microbiote fécal (aFMT), c’est-à-dire la réintroduction de ses propres bactéries collectées avant l’administration de l’antibiotique.

Résultat : les probiotiques standards ont facilement colonisé l’intestin de tous les membres du deuxième groupe. Mais, à la surprise des chercheurs, cette colonisation probiotique a empêché le microbiote intestinal de revenir à la normale, et ce des mois après le traitement antibiotique. En revanche, l’aFMT a favorisé le retour à la normale du microbiote intestinal en seulement quelques jours.

Un nouvel effet indésirable potentiel

« Contrairement au dogme actuel selon lequel les probiotiques sont inoffensifs et profitent à tout le monde, ces résultats révèlent un nouvel effet indésirable potentiel de l’utilisation de probiotiques avec des antibiotiques qui pourraient même avoir des conséquences à long terme », explique le Pr Elinav.

« En revanche, reconstituer l’intestin avec ses propres microbes est un traitement personnalisé qui a permis d’inverser complètement les effets des antibiotiques. »

« Cela ouvre la porte à des diagnostics qui nous mèneraient d’une consommation universelle empirique de probiotiques, qui semble inutile dans de nombreux cas, à une consommation adaptée à chaque individu et pouvant être prescrite à différentes personnes en fonction de leurs caractéristiques de base », suggère son co-auteur Eran Segal.

Publication dans Cell et Cell 6 sept. 2018

Source Pourquoi Docteur

[:en]

Every day, millions of people take probiotics – preparations containing live bacteria that are meant to fortify their immune systems, prevent disease, or repair the adverse effects of antibiotics. Yet the benefits of probiotics have not really been medically proven. It is not even clear if probiotic bacteria really colonize the digestive tract or, if they do, what effects the colonies have on humans and their microbiomes – the native bacteria in their guts. Now, researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science show – in both mice and in humans – that a preparation of 11 strains of the most widely used probiotic families may sometimes be less than beneficial for the user and their microbiome.

Exploring how probiotics truly affect us turned out to be an “inside job”: for the first study, 25 human volunteers underwent upper endoscopies and colonoscopies to sample their baseline microbiome composition and function in different gut regions. Next, 15 of those volunteers were divided into two groups: the first was given the 11-strain probiotic preparation and the second received placebo pills. Three weeks into the four-week treatment, all participants underwent a second upper endoscopy and colonoscopy to assess their response to the probiotics or placebo, then were followed for an additional two months.

The researchers discovered that probiotics’ gut colonization was highly individual. However, they fell into two main groups: the “persisters” had guts that hosted the probiotic microbes while the microbiomes of “resisters” expelled them. The team found they could predict whether a person would be a persister or resister just by examining their baseline microbiome and host gene expression profile. Persisters, they noted, exhibited changes to their native microbiome and gut gene expression profile, while resisters did not have such changes.

Personalized treatment matters

The study that produced these papers was headed by research teams from the labs of Prof. Eran Elinav of the Department of Immunology and Prof. Eran Segal of the Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, in collaboration with Prof. Zamir Halpern, Director of the Gastroenterology Division, Tel Aviv Medical Center. Dr. Niv Zmora, Jotham Suez, Gili Zilberman-Schapira, and Uria Mor from Prof. Elinav’s lab led the two projects, in collaboration with other members of the Elinav and Segal labs and additional scientists and clinicians from Weizmann and elsewhere.

“Our results suggest that probiotics should not be universally given to the public as a ‘one size fits all’ supplement,” says Prof. Elinav. “Instead, they could be tailored to each individual and their particular needs. Our findings even suggest how such personalization might be carried out.” Prof. Segal continues: “These results add to our previous ones on diet that had revealed a similar individual response to foods, and which have highlighted the role of the gut microbiome in driving very specific clinical differences between people.”

Post-antibiotic colonization and the native microbiome

In the second study, the researchers addressed a related question that is of equal importance to the general public, who are often told to take probiotics to counter the effects of antibiotics: Do probiotics colonize the gut following antibiotic treatment, and how does this impact the human host and their microbiome?

The researchers administered wide-spectrum antibiotics to 21 human volunteers, who then underwent an upper endoscopy and colonoscopy to observe the changes to both the gut and its microbiome following the antibiotic treatment. Next, the volunteers were randomly assigned to one of three groups. The first was a “watch and wait” group, where the microbiome was left to recover on its own. The second group was administered the 11-strain probiotic preparation over a four-week period. The third group was treated with an autologous fecal microbiome transplant (aFMT) made up of their own bacteria, which had been collected before giving them the antibiotic.

After the antibiotic had cleared the path, probiotics could easily colonize the human gut – more so than in the previous study in which antibiotics had not been given. To the team’s surprise, the probiotics’ gut colonization prevented the both the host gut’s gene expression and their microbiome from returning to their normal pre-antibiotic configurations for months afterward. In contrast, aFMT resulted in the native gut microbiome recolonizing and the gut gene expression profile returning to normal within days. “These results,” says Prof. Elinav, “reveal a new and potentially alarming adverse side effect of probiotic use with antibiotics that might even bring long-term consequences. In contrast, personalized treatment – replenishing the gut with one’s own microbes – was associated with a full reversal of the drugs’ effects.”

Since probiotics are among the world’s most used over-the-counter supplements, these results may have immediate, broad implications. “Contrary to the current dogma that probiotics are harmless and benefit everyone,” says Prof. Segal, “we suggest that probiotics preparations should be tailored to individuals, or that such treatments such as autologous FMT may be indicated in some cases.”

Publication in Cell and Cell Sept. 6th 2018

Also taking part in the studies were Mally Dori-Bachash, Stavros Bashiardes, Maya Zur, Dana Regev-Lehavi, Rotem Ben-Zeev Brik, Sara Federici, Yotam Cohen, Max Horn, Raquel Linevsky, Meirav Pevnesr-Fischer, and Hagit Shapiro of the Elinav lab; Eran Kotler, Daphna Rothschild, David Zeevi, and Tal Korem of the Segal lab; Andreas E. Moor, Shani Ben-Moshe, and Shalev Itzkovitz of the Itzkovitz lab; Alon Harmelin of the Department of Veterinary Resources; Nitsan Maharshak and Oren Shibolet of the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center; and

Itai Sharon of the Tel-Hai College and the MIGAL Galilee Research Institute.

[:]