Evolution : le chaînon manquant, un fragment de crâne humain datant de 55 000 ans, mis à jour en Israël

[:fr]Les Européens modernes ont hérité d’environ 4 % de gènes des Néandertaliens, ce qui signifie que les deux groupes se sont accouplés à un moment clé dans le passé. Mais la question qui taraudait la communauté scientifique depuis des décennies est, où et quand ? On savait que l’homme moderne et l’homme de Néandertal s’étaient retrouvés au même endroit au même moment, mais aucune preuve physique n’avait été apportée jusque là. La découverte stupéfiante de chercheurs israéliens pourrait bien être la réponse tant attendue. Ils ont découvert un fragment de crâne humain dans la grotte préhistorique Manot (Galilée, Israël).

Recouvert d’une patine de minerais produits par les conditions humides de la grotte, les chercheurs ont pu utiliser des techniques de datation à l’uranium-thorium et déterminer qu’il se situait entre 50 000 à 60 000 années. Ce qui indique que la population humaine originaire d’Afrique aurait migré il y a 65 000 ans. Une analyse morphométrique montre qu’il s’agit du crâne d’un homme moderne ayant des similitudes avec les crânes modernes d’Afrique, d’une part, et les anciens crânes de l’homme moderne d’Europe de l’autre. Le volume du cerveau contenu dans ce crâne était relativement faible, environ 1 100 millilitres, alors que le cerveau moyen moderne atteint environ 1 400 millilitres. Selon les chercheurs, cette découverte est l’une les plus importantes dans l’étude de l’évolution de l’humanité. Elle éclaire une période cruciale : celle de l’apparition de l’homme moderne tel que nous le connaissons aujourd’hui. Elle remet en question l’hypothèse communément admise jusqu’ici, que les deux espèces s’étaient rencontrées il y a 45 000 années quelque part en Europe.

L’étude a impliqué des chercheurs de l’Université de Tel Aviv (Israel Hershkovitz, Viviane Slon) et de l’Université Ben Gourion du Néguev (Ofer Marder). Mais aussi Avner Ayalon, Gal Yasur et Myriam Bar-Matthews de la Commission géologique d’Israël, l’Institut Weizmann des Sciences, Amos Frumkin, Alan Matthews et Mae Goder-Goldberger de l’Université Hébraïque de Jérusalem, Guy Bar-Oz et Reuven Yeshurun de l’Université de Haïfa, Gerhard W. Weber de l’Université de Vienne, de l’Université de Harvard, Bruce Latimer et Mark G. Hans de l’université Case Western Reserve, Elisabetta Boaretto, Bridget Alex, Philipp Gunz et Valentina Caracuta de l’Institut Max Planck, Ralph L. Holloway de l’Université de Columbia, Francesco Berna de l’Université Simon Fraser, Daniella Bar-Yosef Mayer et Hila May du musée Steinhardt d’histoire naturelle (Israël) et Omry Barzilai de la haute autorité des antiquités d’Israël.

Publication Nature, 28 janvier 2015[:en]A team of researchers from the Tel Aviv University, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and the Israel Antiquities Authority reported today in the new issue of Nature Magazine “one of the most important discoveries in the study of human evolution”. The matter in question is a 55,000 year old anatomically modern human skull that was found in the Dan David-Manot Cave in the Western Galilee. This rare skull constitutes the earliest fossilized evidence outside of Africa indicating that today’s human population originated in Africa and migrated from there c. 65,000 years ago. According to the researchers, the discovery sheds light on one of the most dramatic periods in human evolution: the appearance of modern humans as we know him today.

The study of the skull from the Dan David-Manot Cave is a joint project of the Tel Aviv University, Israel Antiquities Authority and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, headed by Professor Israel Hershkovitz, Dr Omry Barzilai and Dr. Ofer Marder, and funded by the Dan David Foundation, Israel Academy of Sciences, Irene Levi Sala CARE Archaeological Foundation, Leakey Foundation and the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The origin and dispersal of modern humans (Homo sapiens) in the Old World has been a major issue that has engaged scientific research for more than 150 years – ever since the publication of “On the Origin of the Species” by Charles Darwin. Considerable progress has been made in the study of physical anthropology since the 1980’s following the introduction of genetic research to the field, which enabled the extraction of DNA from bones and their accurate dating. The results of genetic studies done on modern and fossilized populations in recent years have led researchers to two conclusions: 1) Modern humans originated from an ancient population core, 200,000 years old, from East Africa, which migrated and arrived in our region approximately 100,000 years ago. This hypothesis is supported by fossilized evidence. 2) Today’s modern population has its origins in a later wave of migration that happened some 65,000 years ago. This is the perio d when modern human populations spread from their African origins throughout the Old World and replaced indigenous populations such as the Neanderthals in the Western Asia and Europe. According to this hypothesis proposed by geneticists, these populations comprised the ancient nucleus from which all modern human populations known today have evolved. One of the migration routes by which modern humans spread out across the world passes through the Levant (the Mediterranean basin), which is the only land crossing between Africa and Europe, but until now, no modern human remains that date to the period between 65-45 thousand years ago were discovered.

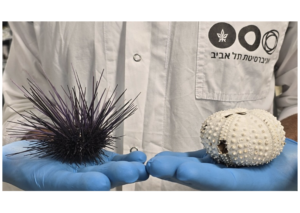

The research picture regarding the origin of modern humans is now becoming clear following the discovery of a modern human calvarium from Manot Cave. Manot Cave is an active karstic cave (stalactite cave) that was discovered by chance in the Western Galilee in 2008 when it was damaged by a bulldozer during construction works. The cave is located 40 kilometers northeast of the famous Mt. Carmel prehistoric caves. To date, five excavation seasons (2010–2014) have been conducted in the cave on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, Tel Aviv University and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, during which an impressive archaeological sequence was documented that yielded remains of several prehistoric cultures.

The Manot skull was found on a bedrock ledge in a small chamber in the center of the cave. Both its inner and outer surfaces were covered with cave deposits that were dated by means of uranium-thorium to 55,000 YBP. A morphometric analysis of the skull shows it is that of a modern human being with similarities to modern skulls from Africa on the one hand and the ancient skulls of modern humans from Europe on the other. The study involved researchers from the Geological Survey of Israel, Weizmann Institute of Science, Hebrew University, University of Haifa, University of Vienna, Harvard University, Case-Western University, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology, Columbia University and Simon Fraser University. At the same time as the skull is being studied, preparations are being made for the development of the cave and readying it for visits by the public. The Ma’ale Yosef Regional Council, Moshav Manot and the Jewish National Fund are partners in the aforesaid development.