USA : Novatrans (Israël) va sauver du broyage des milliards de poussins mâles grâce à des capteurs TeraHertz

[:fr]

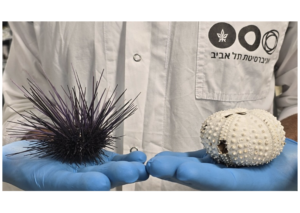

Tous les ans, plus de 9 milliards de poussins dans le monde sont directement envoyés dans des broyeurs par le simple défaut d’être des mâles. La start-up israélienne Novatrans Group a réussi à détecter le genre du futur volatile directement dans l’œuf ce qui pourrait être une vraie révolution dans le domaine. Il est difficile d’imaginer que, chaque année, la moitié des poussins prenant vie voient leurs jours se terminer immédiatement dans un broyeur. Le poussin mâle, en plus de ne pondre aucun œuf, possède moins de viande qu’une poule, ce qui en fait un produit beaucoup moins rentable pour les professionnels du secteur. Sachant que le prix de cet abattage est estimé à plus de 500 millions de dollars par an, la société israélienne Novatrans Group a développé un capteur fonctionnant grâce à des ondes électromagnétiques dans la gamme du THz pour détecter de manière non invasive le genre du futur volatile lorsqu’il se trouve encore dans l’œuf.

En réalité, ce capteur arrive à sonder le gaz qui s’échappe de la coquille et qui possède une signature particulière en fonction du genre de l’animal. La société prévoit de déployer le dispositif pour production dès fin 2017 aux Etats-Unis. Cette avancée technique permettra surement de sauver la vie de milliards de poussins et pourrait également permettre de réinjecter l’argent économisé dans l’élevage de poules en plein air qui voit sa demande fortement monter depuis plusieurs années. Le chairman et fondateur de Novatrans Group est Oren Sadiv, le CEO est Ran Eisenberg.

Rédacteur : Fabien Lafont, post-doctorant à l’Institut Weizmann pour BVST

Source nocamels

————-

Suite aux pressions exercées par l’association The Humane League, les producteurs d’œufs nord-américains ont annoncé qu’ils mettront fin à la cruelle pratique du broyage des poussins mâles. Il faudra cependant attendre 2020 pour que cette technique controversée disparaisse complètement. Cette bonne nouvelle est la résultante d’un accord entre des associations de défense des animaux et la coopérative agricole United Egg Producers, qui regroupe 95% des producteurs d’œufs des Etats-Unis. Elle mettra ainsi un terme à l’abattage de tous les poussins nouveaux-nés mâles, une pratique standardisée outre-Atlantique. Ces derniers, ne pondant pas d’œufs et n’ayant pas les mêmes caractéristiques que les poulets destinés à être consommés, sont triés à la naissance et jetés massivement dans des broyeuses. Aussi choquant que cela puisse paraître, cette méthode est pourtant légale dans de nombreux pays, y compris en France.

Désormais, les éleveurs américains utiliseront une technique – encore en développement – d’identification du sexe des embryons présents dans les œufs avant leur éclosion. Ainsi, les poussins mâles ne verront même pas le jour. Quelques minutes seulement après leur éclosion, les poussins considérés comme « non-désirables » sont jetés par centaines dans des conteneurs géants où ils seront brutalement broyés avec les coquilles d’œufs. Cette décision des producteurs d’œufs américains semble avoir des échos en Europe, l’Allemagne ayant récemment élaboré une loi similaire qui interdira l’abattage des poussins mâles dès 2017. Ailleurs en Europe, la méthode reste malheureusement la norme. Le porte-parole de l’association britannique de défense des animaux Animal Aid déclare à ce propos : les consommateurs doivent prendre conscience qu’en achetant des oeufs, même s’ils proviennent d’élevages en plein-air, ils financent cette pratique.

[:en]Amid the recent, growing opposition to tightly caged hens, another practice in the poultry industry has drawn less notice: All male chicks born at egg farm hatcheries are slaughtered the day they hatch. This is typically done by shredding them alive, in what amounts to a blender.

This mass culling of billions of newborn chicks each year has upset not only animal welfare groups, but the egg industry itself has recognized a need to end the process. And that has fueled a quiet international race to develop technology to determine the gender of a chicken egg before it hatches, known as in-ovo sexing.

Male chicks are “macerated,” as the egg industry calls the slaughter, because according to the hard math of modern-day poultry farming, the males are useless: They cannot grow up to lay eggs, and they’re not the fast-growing breeds that are sold as meat.

Now a Texas-based company that sells eggs from pasture-raised hens has entered the race to make an industrial-scale sexing technology, saying it has developed a method that can be used the day eggs are laid. Vital Farms, whose eggs are carried by 5,000 stores nationwide, told The Washington Post this week that it hopes to make the technology, which it developed in partnership with the Israeli tech firm Novatrans, commercially available within a year.

It says its technology would solve an animal welfare problem as well as a financial one for egg hatcheries, which under current methods spend money incubating eggs for 21 days and then sorting out by hand — and culling — the males that hatch from half of them. Male eggs could instead be sold on grocery shelves, Vital Farms chief executive Matt O’Hayer said.

The wide-scale adoption of in-ovo sexing technology would be another win for chickens, which have become some of the more the unlikely beneficiaries of the animal welfare movement. In recent years, animal rights activists have successfully pressured hundreds of U.S. and international companies into vowing to switch to using only cage-free eggs. That, in turn, has prompted the American egg industry to acknowledge that uncaged hens are the way of the future, although it says farmers — which must overhaul their systems — are not happy about it.

Given the labor and other costs involved, the egg industry has an incentive to stop killing male chicks. Momentum on the issue began to grow in 2014, when Unilever, which owns Hellman’s mayonnaise and other egg-using companies, committed to supporting in-ovo technology research and adopting it. The German government pledged to end male chick culling by 2017, though the country’s parliament later voted down a ban. Animal rights groups’ video investigations of culling methods — which sometimes involve gassing or suffocating chicks — also have become more common.

In contrast to its reluctant acquiescence to the cage-free movement, the U.S. egg industry fairly quickly signed onto supporting an end to chick culling. In June, United Egg Producers, which represents 95 percent of American egg farms, said in an announcement coordinated with the animal rights group the Humane League that it would end the culling by 2020 “or as soon as” the technology is “commercially available and economically feasible.”

[How eggs became a victory for the animal welfare movement]

“We are aware that there are a number of international research initiatives underway in this area, and we encourage the development of an alternative with the goal of eliminating the culling,” Chad Gregory, the president and chief executive of United Egg Producers, said in a statement in June.

Gregory was referring to a handful of ongoing efforts to develop in-ovo sexing technology. At least three initiatives have said they are less than two years away from launching their products.

Egg Farmers of Ontario, a Canadian trade body, told an international egg conference this year that it had patented a process to sort eggs by gender with 95 percent accuracy before incubation, and that it hoped to have a prototype ready by the end of 2016. Researchers at two German universities have said they are working on a method that involves poking a small hole in an eggshell and shining in an infrared light to determine in the first 72 hours of incubation whether it contains male or female chromosomes; they’ve said they expect it to be ready in 2017. A third method, being developed by Dutch start-up In Ovo, would run fluid from each egg through a mass spectrometer to determine the level of a biomarker that the company says can determine gender by the ninth day of incubation. The company has said it could have a working model by mid-2017.

Vital Farms’s work with Novatrans, however, had not been publicized until now. Paul Knepper, president of a subsidiary called Ovabrite that Vital Farms has launched to market its method, said it is different from other technologies in development because it does not involve puncturing the egg and is used on the day eggs are laid, keeping them viable for human consumption.

Knepper said it traps an egg’s metabolic byproducts — which he described as volatile organic compounds “given off by an egg as it ‘breathes’” — that carry a distinct, measurable male or female signature. The two-second-per-egg process is carried out by a device that Knepper said is about the size of a boardroom table…

Full article on Washington Post

[:]