Sud Radio. Géo-ingénierie : "l'institut Weizmann travaille sur une algue pour créer des nuages"

[:fr]

Yolaine de la Bigne. « Pour contrer le changement climatique, des ingénieurs partent dans des délires, la géo-ingénierie, des inventions parfois folles. Alors qu’on va s’oriente les 2°C et que les humains n’ont pas l’air de vouloir changer leurs habitudes, il faut trouver des solutions urgentes pour éviter le four. Certains ne resteront que des projets fous, et tant mieux, car contrôler la nature peut s’avérer dangereux.

Mais parmi les pistes sérieuses qui inspirent beaucoup ces professeurs Tournesol, il y a les nuages, ce miracle du quotidien qui enchante les peintres et nous offre la pluie. Or les nuages abaissent aussi la température de la planète d’où le fantasme de les faire grossir pour faire barrage au rayonnement du soleil. Parmi les idées folles, celle du physicien John Latham qui propose d’injecter des gouttelettes d’eau dans les nuages pour les augmenter et celle de l’ingénieur Stephen Salter qui imagine des navires sans pilote, contrôlés par satellite qui sillonneraient les océans en projetant de l’eau de mer en l’air.

On est un peu dans le délire mais certaines recherches semblent plus réalistes comme celle des israéliens qui travaillent sur l’exosquelette de l’algue Emiliana huxleyi qui prolifère dans l’Atlantique. Elle peut projeter dans l’air, via les embruns, des noyaux de condensation qui pourraient créer des nuages. C’est un phénomène local que l’on vient de découvrir et les chercheurs de l’Institut Weizmann des Sciences (Miri Trainic, Ilan Koren, Shlomit Sharoni, Miguel Frada, Lior Segev, Yinon Rudich, Assaf Vardi) pensent qu’il en existe sans doute ailleurs et que cela pourrait être une solution intéressante vu le nombre impressionnant d’algues dans les océans. A suivre…

On est un peu dans le délire mais certaines recherches semblent plus réalistes comme celle des israéliens qui travaillent sur l’exosquelette de l’algue Emiliana huxleyi qui prolifère dans l’Atlantique. Elle peut projeter dans l’air, via les embruns, des noyaux de condensation qui pourraient créer des nuages. C’est un phénomène local que l’on vient de découvrir et les chercheurs de l’Institut Weizmann des Sciences (Miri Trainic, Ilan Koren, Shlomit Sharoni, Miguel Frada, Lior Segev, Yinon Rudich, Assaf Vardi) pensent qu’il en existe sans doute ailleurs et que cela pourrait être une solution intéressante vu le nombre impressionnant d’algues dans les océans. A suivre…

L’Australie est très active dans le domaine également et le gouvernement a débloqué des fonds pour tenter de sauver la grande barrière de corail qui se porte très mal ce qui est très inquiétant pour notre avenir. Et elle travaille aussi pour éclaircir les nuages. Comment ? En y injectant des petites gouttelettes d’eau de mer. Quand l’eau se vaporise, il resterait des particules de sel qui flotterait dans l’air ce qui permettrait de mieux réfléchir la lumière solaire et du coup de faire barrage pour protéger les coraux de la chaleur, un peu comme un parasol géant. Cela semble complètement farfelu mais le but est de nous faire gagner du temps en attendant des solutions plus durables. Et les scientifiques y croient, espérons qu’ils ne soient pas trop dans les nuages pour le coup ! »

Publication in iScience, 31 août 2018

Sources : Sud Radio, koide9enisrael, Esther Amar pour Israël Science Info

[:en]

The shredded carcasses of microscopic marine algae could play an important role in the formation of clouds over the world’s oceans, a new study has found.

We all know clouds form as microscopic water droplets in the air condense on the surface of microscopic particles. These particles can be soluble – such as where salt crystals soak up the water – or insoluble, like dust, collecting water on their external surface.

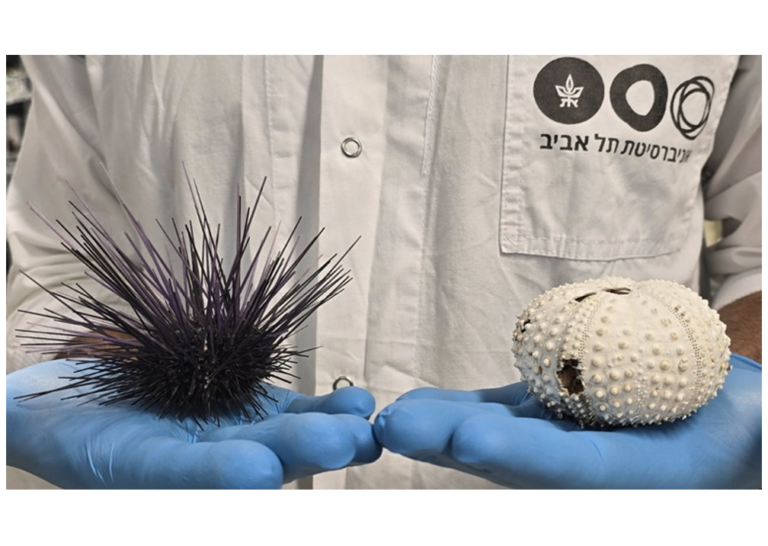

A single-celled species of alga, or phytoplankton, called Emiliania huxleyi could be responsible for far more of these cloud seeding particles than previously thought. Blown apart from the inside by a common virus, their hard shells form insoluble particles on which water droplets condense in the atmosphere.

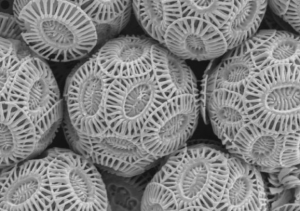

This phytoplankton is ubiquitous throughout the world’s oceans. It’s so common, you’ve probably seen pictures of its familiar calcium carbonate shell made up of tiny plates called coccoliths.

When the conditions are right, the alga blooms, its vast numbers colouring the oceans bright shades of turquoise in spite of the microscopic size of the individual organisms.

When they – and other shelled phytoplankton – die, most of their coccoliths end up as part of the sediment on the ocean floor.

But not all. Traces of E. huxleyi coccoliths have been found in sea spray, borne aloft by breaking waves, or bubbles in the water.

But not all. Traces of E. huxleyi coccoliths have been found in sea spray, borne aloft by breaking waves, or bubbles in the water.

Sea spray aerosols play an important role in regulating Earth’s climate, and the presence of phytoplankton has been found to increase the number of cloud droplets over the ocean.

But the role these algae play in cloud formation, if any, hasn’t been entirely clear.

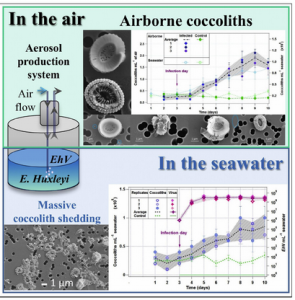

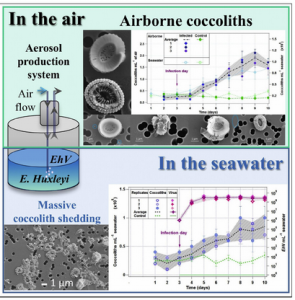

To try to figure it out, a team of researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel (Miri Trainic, Ilan Koren, Shlomit Sharoni, Miguel Frada, Lior Segev, Yinon Rudich, Assaf Vardi) grabbed a whole bunch of E. huxleyi and infected half of them with a virus that commonly infects them in nature. The other half were kept virus-free as a control.

At the beginning of the experiment, each millilitre of water contained around 20 million empty coccoliths. After 5 days, this number had more than tripled for the infected algae, compared to the control.

Then they used bubbles to mimic the natural churning of the ocean that would create sea spray. There was 10 times more coccolith material in the air above the infected algae than above the control group.

But there’s more. Because the coccoliths are so small and light, they stay airborne for a long time – they fall « 25 times slower compared with sea salt particles with the same dimension, » the researchers wrote.

This means in conditions where heavier particles might fall, the coccolith fragments don’t, leaving them to concentrate in the air – and perhaps play a significant role in cloud formation.

On the other hand, they may do the opposite.

Living E. huxleyi, along with other marine microorganisms, produces a gas called dimethyl sulfide, which helps drive cloud formation. It’s possible that fragments of calcium carbonate in the air react with the dimethyl sulfide and destroy it, reducing rather than increasing cloud propagation.

The next step to try and find out which of these scenarios is the case is to observe a bloom in action.

Publication in iScience August 31th 2018

Source sciencealert

[:]