Université de Haïfa (Israël) : l'aquaculture est née il y a 3500 ans en Méditerranée orientale

[:fr]

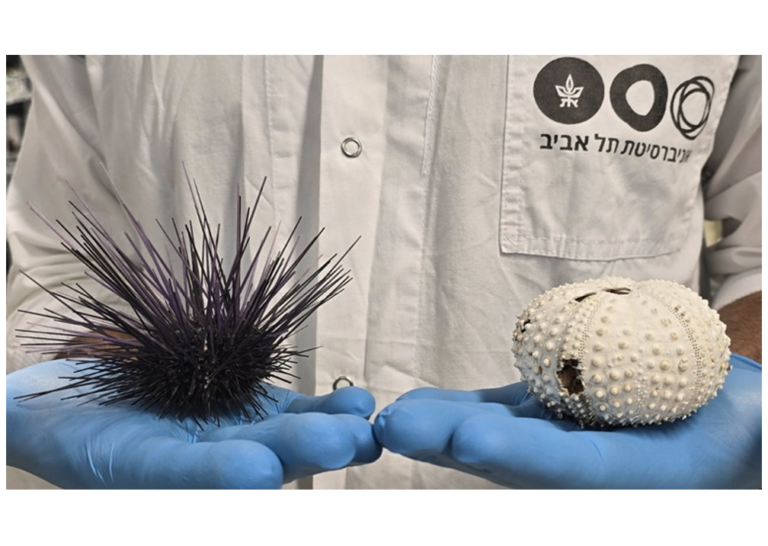

Les dents de la dorade royale ont révélé le secret : l’aquaculture ancienne est née en Méditerranée orientale il y a 3500 ans. C’est la conclusion d’une étude menée par l’Université de Haïfa (Israël), le Collège universitaire Oranim, la recherche océanographique et limnologique en Israël et des chercheurs allemands des universités de Mayence et de Göttingen. Selon l’étude, l’aquaculture était pratiquée en Méditerranée, constituant la première preuve à ce jour dans le monde. « Selon les nouvelles découvertes, ainsi que les découvertes archéologiques de la fin du bronze et de l’âge du fer (période biblique), l’Egypte est devenue une superpuissance dans l’aquaculture, exportant du poisson vers le nord, y compris vers les villes israélites et cananéenne« , explique Dr Guy Bar-Oz de l’Université de Haïfa, l’un des auteurs de l’étude.

L’aquaculture se développe rapidement aujourd’hui en raison de la demande croissante de consommation de poisson, ce qui a conduit à une révolution bleue. Mais quand les humains ont-ils commencé à développer une aquaculture organisée ? Les peintures murales de l’Égypte ancienne, datant du troisième siècle avant notre ère, comprennent des représentations de la pêche et de la découpe du poisson à des fins de commercialisation. Mais jusqu’à présent, nous n’avions aucune preuve archéologique ou empirique de l’aquaculture d’une période aussi précoce. Dans cette étude, financée par le Conseil européen de la recherche (ERC), le Conseil allemand de la recherche (DFG) et la Fondation israélienne de la science (ISF), les chercheurs ont découvert les premières preuves empiriques antérieures aux peintures murales de plusieurs siècles.

« L’étude reposait sur un examen des isotopes de l’oxygène dans les dents de la dorade royale, qui révélait où les poissons étaient élevés pendant les premiers mois de leur vie, au moment de la formation de leurs dents. Le rapport entre les isotopes de l’oxygène 18 et de l’oxygène 16 varie dans la nature selon un schéma fixe reflétant la température de salinité de l’eau. En conséquence, l’examen du rapport entre ces isotopes dans les dents des poissons modernes et anciens nous permet d’identifier et de calculer la température de l’eau et la salinité dans lesquelles les dents ont été créées. Une fois ces données en main, on peut les recouper avec d’autres preuves géologiques, archéologiques et historiques concernant la température et la salinité de l’eau de mer dans diverses zones, identifiant ainsi l’habitat possible dans lequel le poisson a été élevé et sa période de vie« , explique le Dr Sisma-Ventura.

L’étude a échantillonné plus de 100 dents de dorades dorées provenant de divers sites archéologiques en Israël, notamment des sites côtiers tels que Dor et Ashkelon, ainsi que des sites intérieurs tels que Jérusalem et Hazor. L’échantillon de dents couvrait une période chronologique de plus de 10 000 ans, allant du néolithique primitif (début de la révolution agricole) au début de la période islamique (VIIe-VIIIe siècles).

« Les résultats ont montré que dans les périodes antiques, il y a environ 3500 ans, la dorade royale était capturée dans deux zones principales : en pleine mer et dans les anciennes lagunes côtières salées. Cependant, il y a environ 4000 ans, lorsque le niveau de la mer s’est stabilisé, un changement radical s’est produit et la plupart des poissons ont été capturés dans un seul habitat : le lagon salin de Sabhat Bardawil, au nord du Sinaï. L’examen du rapport entre les isotopes a révélé les niveaux de température et de salinité dans lesquels les poissons ont été élevés à partir de cette période. Lorsque nous avons examiné tous les sites possibles, nous avons constaté que seul le lagon salin de Bardawil correspondait à ce profil chimique spécifique », ont expliqué les chercheurs.

L’étude a également révélé que pendant les périodes bibliques, la dorade royale était le principal poisson importé sur des sites situés au centre d’Israël. La taille du poisson était également compatible avec la transition vers l’aquaculture. Il y a 3 500 ans, les poissons capturés présentaient une grande variété de tailles, petites et grandes, mais à partir de ce moment, la gamme de tailles s’est rétrécie. « À l’époque biblique, les poissons importés avaient tous la taille d’une assiette, environ 500 grammes et une longueur de 40 cm, exactement comme nous le voyons dans les poissons élevés en aquaculture moderne», a déclaré le Dr Zohar.

Les nouvelles découvertes, associées à des preuves archéologiques supplémentaires datant des âges du bronze et du fer tardifs, révèlent un modèle d’aquaculture et de liens commerciaux entre l’Égypte – le puissant empire au sud – et les anciennes colonies de peuplement.

L’étude était dirigée par le Dr Guy Sisma-Ventura de la recherche océanographique et limnologique israélienne, en collaboration avec les professeurs Guy Bar-Oz, Omri Lernau et Ayelet Gilboa de l’Institut d’archéologie Zinman de l’Université de Haïfa ; le Pr Dorit Sivan du département des civilisations maritimes de l’Université de Haïfa ; Dr. Irit Zohar du Collège académique d’Oranim et de l’Institut d’archéologie Zinman de l’Université de Haïfa ; Andreas Pack de l’Université de Göttingen ; et le Pr Thomas Tütken de l’Université de Mayence.

Publication dans Nature Scientific Reports,

Traduction/adaptation Esther Amar pour Israël Science Info

[:en]

The teeth of the gilthead seabream revealed the secret: ancient aquaculture took place in our region as long as 3,500 years ago. This finding emerges from a new study undertaken by the University of Haifa, Oranim Academic College, Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research, and German researchers from the Universities of Mainz and Göttingen. According to the study, which was published in the prestigious journal Nature Scientific Reports, aquaculture was pursued in the Mediterranean Sea, constituting the earliest empirical evidence today anywhere in the world. “According to the new findings, together with archeological findings from the Late Bronze and Iron Age (the Biblical period), we find that Egypt became a superpower in aquaculture, exporting fish to the north – including to the Israelite and Canaanite cities,” explains Dr. Guy Bar-Oz of the University of Haifa, one of the authors of the study.

Aquaculture is developing rapidly today due to growing demand for the consumption of fish, leading to what has been dubbed the “blue revolution.” But when did humans first begin to develop organized aquaculture? Wall paintings from ancient Egypt, dating back to the third century BCE, include depictions of fishing and the cutting of fish for marketing. But until now we had no archeological or empirical evidence of aquaculture from such an early period. In the present study, which was funded by the European Research Council (ERC), the German Research Council (DFG), and the Israel Science Foundation (ISF), the researchers found early empirical evidence predating the wall paintings by several centuries. The study was led by Dr. Guy Sisma-Ventura of Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research, together with Prof. Guy Bar-Oz, Prof. Omri Lernau, and Prof. Ayelet Gilboa of the Zinman Institute of Archaeology at the University of Haifa; Prof. Dorit Sivan of the Department of Maritime Civilizations at the University of Haifa; Dr. Irit Zohar of Oranim Academic College and the Zinman Institute of Archaeology at the University of Haifa; Prof. Andreas Pack of the University of Göttingen; and Prof. Thomas Tütken of the University of Mainz.

The study was based on an examination of the oxygen isotopes in the teeth of gilthead seabream, which reveals where the fish were raised during the first few months of their life, when their teeth were formed. “The ratio of oxygen-18 and oxygen-16 isotopes varies in nature according to a fixed pattern reflecting the temperature of salinity of the water. Accordingly, examining the ratio between these isotopes in teeth of modern and ancient fish allow us to identify and calculate the water temperature and salinity in which the teeth were created. Once we have these data, we can cross-reference them with other geological, archeological, and historical evidence regarding the temperature and salinity of seawater in various areas, thereby identifying the possible habitat in which the fish was raised and the period in which it lived,” Dr. Sisma-Ventura explains.

The current study samples over 100 teeth from gilthead seabream gathered from various archeological sites in Israel, including coastal sites such as Dor and Ashkelon, as well as inland sites such as Jerusalem and Hazor. The sample of teeth covered a chronological period extending over 10,000 years, from the early Neolithic period (the beginning of the Agricultural Revolution) through to the early Islamic period (the 7th-8th centuries CE).

The findings showed that in ancient periods some 3,500 years ago, gilthead seabream were caught in two main areas: in the open sea and in ancient saline coastal lagoons. However, some 4,000 years ago, as sea levels stabilized, a dramatic change occurred and most of the fish was caught in a single habitat: the saline lagoon at Sabhat Bardawil in Northern Sinai. “The examination of the ratio between the isotopes indicated the temperature and salinity levels at which the fish were raised from this period. When we examined all the possible sites, we found that only the saline lagoon at Bardawil matched this specific chemical profile,” the researchers explained.

The study also found that during the Biblical periods, the gilthead seabream was the main fish imported to sites in the center of Israel. The size of the fish was also consistent with the transition to aquaculture. In periods 3,500 years ago, the fish caught showed a wide variety of sizes, small and large, but from this point forward, the range of sizes narrowed. By the Biblical period, the imported fish were all “plate sized” – “around 500 grams and 40 cm long, just as we see in fish raised by modern aquaculture,” Dr. Zohar noted.

The new findings, together with additional archeological evidence from the Late Bronze and Iron Ages, reveal a pattern of aquaculture and commercial ties between Egypt – the mighty empire to the south – and the ancient settlements.

Publication in Nature Scientific Reports,

[:]