Weizmann (Israël) et le Bard College (NY) montrent le coût environnemental d'un steak

[:fr]

Alon Shepon and Prof. Ron Milo

D’après les prédictions des chercheurs, si les Américains du Nord renonçaient à leur bifteck en faveur du poulet, il serait possible de nourrir 40% de personnes en plus, soit entre 120 et 140 millions de personnes. Si on ose pousser un peu plus loin ce petit jeu et imaginer nos amis d’outre-Atlantique attablés devant du soja, des lentilles et des levures, alors il deviendrait possible de nourrir 190 millions d’individus supplémentaires.

Changer drastiquement les habitudes alimentaires de la population du jour au lendemain est certes utopique, mais une prise de conscience et des modifications progressives pourraient à terme réduire l’épuisement des sols, l’émission de gaz à effet de serre et les excès de nitrates dus à l’utilisation d’engrais.

Rédacteur : Tirtsa Ackermann, VI chercheuse à l’Université Hébraïque de Jérusalem pour BVST

Sources :

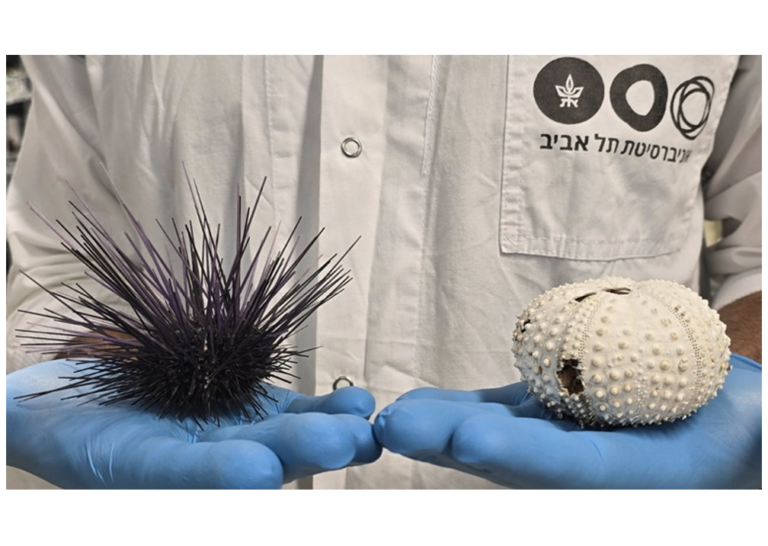

[:en]How much does a steak really cost? Or chicken nuggets; or a plate of hummus? New research by Prof. Ron Milo and Alon Shepon of the Plant and Environmental Sciences Department, together with Prof. Gideon Eshel of Bard College, New York, took a look at the real figures – including the environmental costs – of the different foods we eat. The research appeared in Environmental Research Letters.

The data for the study came from figures for cattle and poultry growing and consumption in the US. To compare, the researchers calculated the nutritional value of each – usable calories and protein – versus the environmental cost. The latter included the use of land for fodder or grazing and the emission of greenhouse gases in both growing the food and in growing the animals themselves.

Alon Shepon and Prof. Ron Milo

Chickens, according to the study, produce much more edible meat per kilogram of feed consumed, and they produce their meat faster than cattle, meaning more can be grown on the same amount of land. For every 100 calories and 100 grams of protein fed to beef cattle, the consumer ends up with around three calories and three grams of protein. For poultry, that figure is about 13 calories and 21 grams of protein.

The researchers then asked what would happen if the entire population of the US was persuaded to change their diet from a beef-heavy plan to one based on chicken. Their answer: It would be possible to feed 40% more people – 120-140 million – with the same resources.

What would happen if the same population was persuaded to adopt an entirely plant-based diet? That is, instead of using land to grow cow or chicken feed and then eating the animals, to use that land to grow nutritional crops — mainly legumes, including peanuts, soya, garbanzos and lentils. These can supply all of a person’s nutritional requirements (except vitamin B12, which can be obtained from nutritional yeast).

If we changed our diet, we would change the environmental price we pay, with every meal

A separate study, published in Environmental Science and Technology, suggests that an extra 190 million people could eat off the same environmental resources in this way.

Shepon says: “If we changed our diet, we would change the environmental price we pay, with every meal. Eating a plant-based diet can both meet our nutritional requirements and save on land use, as well as the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere and excess nitrogen from fertilizers into the water supply. These are real costs that we all bear, especially when people eat beef.”

Prof. Ron Milo’s research is supported by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; Dana and Yossie Hollander, Israel; and the Larson Charitable Foundation. Prof. Milo is the incumbent of the Charles and Louise Gartner Professorial Chair.

Environmental research letters, October 2016[:]