Weizmann (Israël) : le phytoplancton fixe autant de carbone qu’une forêt tropicale

[:fr]Le Dr Assaf Vardi, microbiologiste marin du département des Sciences du végétal de l’Institut Weizmann, ainsi que le Pr Ilan Koren, qui travaille sur la physique des nuages, et le Dr Yoav Lehahn, océanographe, tous deux du département des Sciences de la Terre et des planètes font progresser les recherches sur le rôle du phytoplancton dans la régulation du contenu carbonique de l’atmosphère.

Lorsqu’on parle de fixation globale du carbone, c’est-à-dire de pompage du carbone de l’atmosphère et de sa fixation par photosynthèse dans des molécules organiques, une mesure correcte est la clé de la réussite pour comprendre ce processus. Selon certaines estimations, presque la moitié du carbone organique dans le monde est fixée par des organismes marins appelés phytoplancton. Ce sont des organismes photosynthétiques monocellulaires qui constituent moins d’un pour cent de la biomasse photosynthétique totale de la Terre.

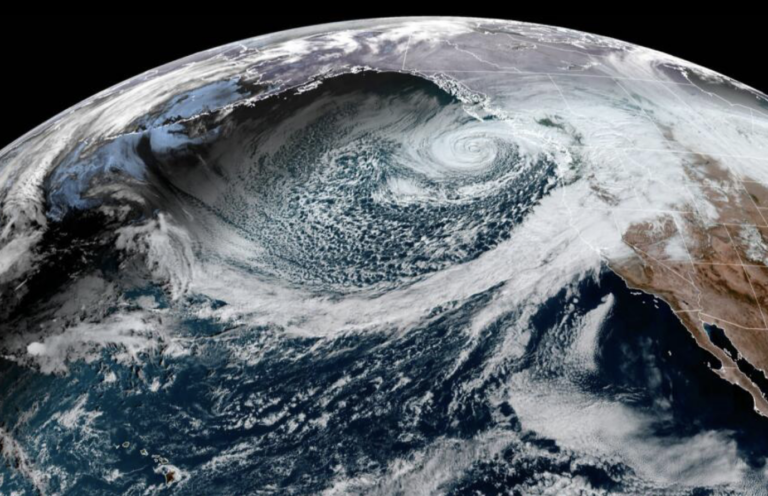

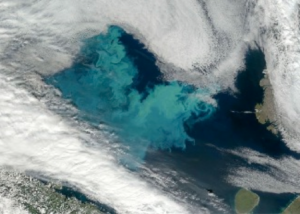

Petits, les organismes phytoplanctoniques peuvent cependant être observés de l’espace : ils prolifèrent en efflorescences pouvant s’étendre sur des milliers de kilomètres carrés, formant sur l’océan des taches de couleurs que les satellites peuvent repérer et mesurer. Ces efflorescences ont tendance à grandir rapidement et à disparaître à l’improviste. Quelle quantité de carbone une efflorescence de ce genre peut-elle fixer, et qu’arrive-t-il à ce carbone quand l’efflorescence disparaît ? Cela dépend en partie de ce qui tue l’efflorescence. Si elle est essentiellement mangée par d’autres êtres vivants marins, par exemple, son carbone passe dans la chaîne alimentaire. Si le phytoplancton manque de nourriture ou s’il est infecté par des virus, le processus est plus compliqué. Des organismes morts qui coulent peuvent emporter leur carbone au fond de l’océan. Mais d’autres peuvent être dévorés à la surface de l’eau par certaines bactéries qui emportent le carbone organique, puis le renvoient dans l’atmosphère par leur respiration.

Les trois chercheurs, Vardi, Koren et Lehahn, se sont demandé s’il est possible d’utiliser les données satellites pour détecter les signes de la disparition d’une efflorescence suite à une infection virale, possibilité que le Dr Vardi a étudiée sur les efflorescences océaniques naturelles, et aussi en laboratoire. Lors d’une récente croisière de recherche à proximité de l’Islande, avec des collègues de l’université Rutgers et du Woods Hole Oceanic Institute, les chercheurs ont pu recueillir des données sur les interactions algues-virus et leurs effets sur les cycles du carbone dans l’océan.

En combinant les données satellites avec les mesures qu’ils ont prises sur le terrain, ils ont pu, pour la première fois, mesurer l’effet des virus sur les efflorescences de phytoplancton dans de vastes zones de haute mer. Les chercheurs ont d’abord dû identifier un sous-ensemble particulier de taches dans l’océan dans lequel des processus physiques tels que des courants n’avaient pas affecté les efflorescences, et ils ont pu observer uniquement les effets biologiques. Puis, en suivant une efflorescence dans l’une de ces zones, ils ont réussi à retracer l’ensemble de son cycle de vie. Ceci leur a permis de quantifier le rôle des virus dans la disparition de cette efflorescence particulière. Leurs conclusions ont été vérifiées à l’aide de données accumulées lors d’une expédition de recherche nord-atlantique.

Les chercheurs ont estimé qu’une étendue d’algues d’environ 1000 kilomètres carrés – qui se forme en une ou deux semaines – peut fixer environ 24 000 tonnes de carbone organique – comme le ferait une surface identique de forêt tropicale. Du fait qu’une infection virale peut rapidement éliminer une efflorescence entière, le fait de pouvoir, depuis l’espace, observer et mesurer ce processus pourrait largement contribuer à la compréhension et à la quantification du renouvellement du cycle carbonique et de sa sensibilité aux conditions de stress environnemental, parmi lesquelles les virus marins.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982214009099

La recherche du professeur Ilan Koren est financée par : J&R Center for Scientific Research et par la succession de M. Raymond Lapon.

La recherche du docteur Assaf Vardi est financée par : Roberto and Renata Ruhman (Brésil) ; Selmo Nussenbaum (Brésil) ; Brazil-Israel Energy Fund ; Lord Sieff of Brimpton Memorial Fund ; European Research Council ; et la succession de Samuel et Alwyn J. Weber. Le docteur Vardi est titulaire de la Edith and Nathan Goldenberg Career Development Chair.[:en]When we talk about global carbon fixation –“pumping” carbon out of the atmosphere and fixing it into organic molecules by photosynthesis – proper measurement is key to understanding this process. By some estimates, almost half of the world’s organic carbon is fixed by marine organisms called phytoplankton – single-celled photosynthetic organisms that account for less than one percent of the total photosynthetic biomass on Earth.

Dr. Assaf Vardi, a marine microbiologist of the Weizmann Institute’s Plant Sciences Department, and Prof. Ilan Koren, a cloud physicist, and Dr. Yoav Lehahn, an oceanographer, both from the Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, realized that by combining their interests, they might be able to start uncovering the role that these minuscule organisms play in regulating the carbon content of the atmosphere.

Tiny as they are, phytoplankton can be seen from space: They multiply in blooms that can reach thousands of kilometers in area, coloring patches of the ocean that can be tracked and measured by satellites. These blooms have a tendency to grow quickly and disappear suddenly. How much carbon does such a bloom fix, and what happens to that carbon when the bloom dies out? That depends, in part on what kills the bloom. If it is mostly eaten by other marine life, for example, its carbon will be passed up the food chain. If the phytoplankton are starved or infected with viruses, however, the process is more complicated. Dead organisms that sink may take their carbon to the ocean floor with them. But others may be scavenged by certain bacteria the surface waters; these remove the organic carbon and release it back into the atmosphere through their respiration.

Vardi, Koren and Lehahn asked whether one can use the satellite data to detect the signs of the demise of a bloom due to viral infection, an occurrence that Vardi has investigated in natural oceanic blooms and in the lab. During a recent research cruise near Iceland with colleagues from Rutgers University and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, the researchers were able to collect data on the algal-virus interactions and their effect on carbon cycles in the ocean.

By combining satellite data with their field measurements, they were able, for the first time, to measure the effect of viruses on phytoplankton blooms on large, open ocean areas. To do this, the scientists first had to identify a special subset of ocean patches in which such physical processes as currents did not affect the blooms – so they could observe just the biological effects. Then, following a bloom in one of these patches, they managed to trace its whole life cycle. This enabled them to quantify the role of viruses in the demise of this particular bloom. Their conclusions were verified in data collected in a North-Atlantic research expedition.

The scientists estimated that an algal patch of around 1,000 sq km – which forms within a week or two – can fix around 24,000 tons of organic carbon – equivalent to a similar area of rain forest. Since a viral infection can rapidly wipe out an entire bloom, the ability to observe and measure this process from space may greatly contribute to understanding and quantifying the turnover of carbon cycle and its sensitivity to environmental stress conditions, including marine viruses.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982214009099

Prof. Ilan Koren’s research is supported by the J&R Center for Scientific Research; the Scholl Center for Water and Climate Research; and the estate of Raymond Lapon.

Dr. Assaf Vardi’s research is supported by Roberto and Renata Ruhman, Brazil; Selmo Nussenbaum, Brazil; the Brazil-Israel Energy Fund; the Lord Sieff of Brimpton Memorial Fund; the European Research Council; and the estate of Samuel and Alwyn J. Weber. Dr. Vardi is the incumbent of the Edith and Nathan Goldenberg Career Development Chair.

The Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, is one of the world’s top-ranking multidisciplinary research institutions. Noted for its wide-ranging exploration of the natural and exact sciences, the Institute is home to scientists, students, technicians and supporting staff. Institute research efforts include the search for new ways of fighting disease and hunger, examining leading questions in mathematics and computer science, probing the physics of matter and the universe, creating novel materials and developing new strategies for protecting the environment.[:]