Weizmann (Israël) : mâles ou femelles, un récepteur régule différemment les réactions au stress

[:fr]On sait que le stress canalise certaines ressources de notre corps, dont l’activité n’est pas toujours nécessaire, afin qu’elles assurent des fonctions indispensables à notre santé. Le stress altère ainsi l’échange de substances indispensables à la vie de tous les jours. Des chercheurs de l’Institut Weizmann des Sciences en Israël ont mené ont étudié un récepteur qui se trouve dans le cerveau des souris, et ils sont arrivés à une conclusion surprenante au point que leurs résultats pourraient permettre d’améliorer à l’avenir le développement de médicaments destinés au traitement de problèmes liés au stress, et aussi à des troubles alimentaires.

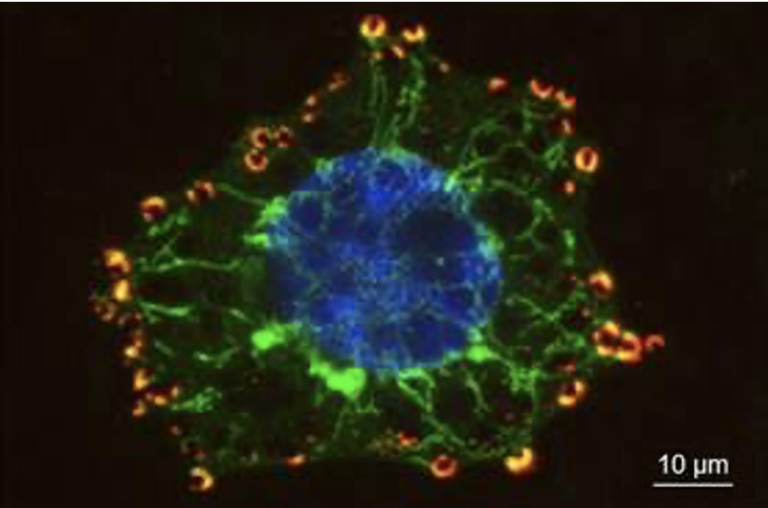

Lorsqu’une personne est confrontée au stress, les cellules se trouvant dans l’hypothalamus intensifient la production d’un récepteur – le CRFR1. On savait déjà que ce récepteur contribue à une activation rapide du système nerveux sympathique en réponse au stress, par exemple en augmentant la fréquence cardiaque. Mais du fait que cette région du cerveau régule aussi l’échange des matières dans le corps, le groupe a eu l’idée que le récepteur CRFR1 pourrait, lui aussi, jouer un rôle.

Le Pr Chen et son groupe ont caractérisé les cellules dans une certaine zone de l’hypothalamus, et ils ont trouvé que le récepteur s’exprime dans la moitié environ de celles qui éveillent l’appétit et répriment la consommation d’énergie. Ces cellules agissent sur l’une des deux populations essentielles de l’hypothalamus, alors que d’autres cellules font progresser la satiété et la combustion d’énergie. La Dr Kuperman dit que « cela a vraiment été une surprise car, intuitivement, nous nous attendions à ce que le récepteur s’exprime dans les cellules qui suppriment la faim. »

Ensuite, les chercheurs ont éliminé le récepteur CRFR1 chez des souris de laboratoire, uniquement dans les cellules de l’hypothalamus qui encouragent l’appétit, et ils ont ensuite observé comment ceci affecte leurs fonctions corporelles. Au début, ils n’ont vu aucun changement notable, ce qui confirmait le fait que ce récepteur était réservé aux situations de stress, mais lorsqu’ils ont exposé les souris au stress – au froid ou à la faim – ils ont eu une autre surprise.

Lorsqu’il est exposé au froid, le système nerveux sympathique active un type de graisse particulier qu’on appelle ‘tissu adipeux brun’, qui produit la chaleur nécessaire pour maintenir la température interne du corps. Lorsqu’on a enlevé le récepteur, la température du corps est tombée brutalement – mais seulement chez les souris femelles. Même après cela, leurs températures ont eu du mal à se stabiliser, alors que les souris mâles n’ont montré pratiquement aucun changement….

Article complet dans Israël Science Info N°19 version papier – cliquez sur Je m’abonne

Publication dans la revue Cell Metabolism[:en]How does stress, which, among other things, causes our bodies to divert resources from non-essential functions, affect the basic exchange of materials that underlies our everyday life? Weizmann Institute of Science researchers investigated this question by looking at a receptor in the brains of mice, and they came up with a surprising answer. The findings may in the future aid in developing better drugs for stress-related problems and eating disorders.

Dr. Yael Kuperman began this study as part of her doctoral research in the lab of Prof. Alon Chen of the Neurobiology Department. Kuperman, presently a staff scientist in the Veterinary Resources Department, Chen and research student Meira Weiss focused on an area of the brain called the hypothalamus, which has a number of functions, among them helping the body adjust to stressful situations, controlling hunger and satiety, and regulating blood glucose and energy production.

When stress hits, cells in the hypothalamus step up production of a receptor called CRFR1. It was known that this receptor contributes to the rapid activation of a stress-response sympathetic nerve network – increasing heart rate, for example. But since this area of the brain also regulates the body’s exchange of materials, the team thought that the CRFR1 receptor might play a role in this, as well.

Chen and his group characterized the cells in a certain area of the hypothalamus, finding that the receptor is expressed in around half of those that arouse appetite and suppress energy consumption. These cells comprise one of two main populations in the hypothalamus – the second promotes satiety and burning energy. “This was a bit of a surprise,” says Kuperman, “as we would instinctively expect the receptor to be expressed on the cells that suppress hunger.”

To continue investigating, the researchers removed the CRFR1 receptor just from the cells that arouse appetite in the hypothalamus, in lab mice, and then observed how this affected their bodily functions. At first, they did not see any significant changes, confirming that this receptor is saved for stressful situations. When they exposed the mice to stress – cold or hunger – they got another surprise.

When exposed to cold, the sympathetic nervous system activates a unique type of fat called brown fat, which produces heat to maintain the body’s internal temperature. When the receptor was removed, the body temperature dropped dramatically – but only in the female mice. Even afterward their temperatures failed to stabilize, while male mice showed hardly any change.

Fasting produced a similarly drastic response in the female mice. Normally when food is scarce, the brain sends a message to the liver to produce glucose, conserving a minimum level in the blood. But when food was withheld from female mice missing the CRFR1 receptor, the amount of glucose their livers produced dropped significantly. In hungry male CRFR1-deficient mice, like those exposed to cold, the exchange of materials in their bodies was barely affected.

“We discovered that the receptor has an inhibitory effect on the cells, and this is what activates the sympathetic nervous system,” says Kuperman.

Among other things – revealing exactly how this receptor works and how it contributes to the stress response – the findings show that male and female bodies may exhibit significant differences in the ways that materials are exchanged under stress. Indeed, the fact that the receptor suppresses hunger in females may help explain why women are much more prone to eating disorders than men.

Because drugs can enter the hypothalamus with relative ease, the findings could be relevant to the development of treatments for regulating hunger or stress responses, including anxiety disorders or depression. Indeed, several pharmaceutical companies have already begun developing psychiatric drugs to block the CRFR1 receptor. The scientists caution, however, that because the cells are involved in the exchange of materials, blocking the receptor could turn out to have such side effects as weight gain.

Publication in Cell Metabolism[:]