Weizmann (Israël) montre le rôle clé du microbiote intestinal dans l'obésité et l'effet yo-yo

[:fr]Huffingtonpost. Après un régime, on finit souvent par récupérer les kilos perdus. Ce serait même le cas dans 80% des tentatives, selon une étude de 2015. Résoudre ce problème, dans un monde où 44% de la population est en surpoids, est essentiel. Sauf que l’on ne sait pas vraiment à quoi est dû cet « effet yo-yo ».

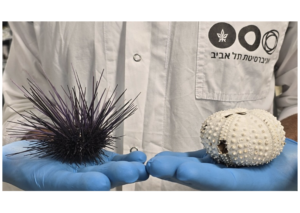

Une équipe de chercheurs de l’Institut Weizmann des Sciences (Israël) explique avoir trouvé la clé qui manquait. Elle se situe dans le microbiote intestinal (flore intestinale), soit les milliards de bactéries et microbes qui vivent à l’intérieur des hommes et des animaux.

Les chercheurs ont étudié* plusieurs souris qui étaient soumises à des régimes alimentaires différents et ont remarqué quelque chose qui, jusqu’alors, avait échappé à tout le monde. Chez les souris obèses, une diète plus équilibrée entraîne une baisse de poids et, bien évidemment, une modification d’autres caractéristiques du corps des rongeurs. Sauf une.

« Le marqueur qui nous manquait »

En effet, la composition du microbiome des souris obèses n’est évidemment pas la même que celle de souris avec un poids normal. Sauf qu’une fois le régime effectué, les souris obèses gardent la même « signature » de leur microbiome, alors que « tous les autres paramètres retournent à la normale », a précisé Eran Elinav, auteur principal de l’étude.

« C’est peut-être le marqueur que nous pourrions utiliser », estime-t-il. Mais pourquoi et comment le microbiote intestinal pourrait-il influencer la reprise de poids après un régime ? Les chercheurs n’ont pas encore de réponse définitive. Mais d’après leurs résultats, les auteurs penchent pour le niveau de flavonoïdes, des anti-oxydants que l’on retrouve dans notre intestin, mais aussi dans les plantes.

Ce taux de flavonoïdes a notamment un impact négatif sur la dépense d’énergie de l’hôte (la souris en l’occurrence). Ce qui veut dire que « plus d’énergie est transformée en gras » pour les souris ayant subi un régime que pour celles n’ayant jamais été obèses, précise Eran Segal.

Vérifier l’impact sur l’homme et trouver un traitement

En utilisant une intelligence artificielle, les chercheurs ont même réussi à prédire le poids qu’une souris va reprendre après un régime, uniquement en analysant son microbiome. Si cette découverte est importante, il faudra encore des années de recherches pour mieux comprendre le phénomène.

« De futures études devraient examiner le potentiel clinique de l’utilisation des flavonoïdes, ainsi que de la modulation d’autres composés du microbiome », comme l’acide biliaire, dont la quantité reste anormalement élevée après un régime, précisent les auteurs de l’étude.

La prochaine étape consiste évidemment « à étudier cela sur les humains, notamment ceux souffrant d’obésité », affirme Eran Segal. « Des essais cliniques sont en cours en Israël » à ce sujet, précise-t-il. « Nous observons les changements du microbiome de personnes obèses et d’un poids normal, ainsi que les changements après un régime »,

Il n’est évidemment pas certain que ce qui a été observé chez la souris se retrouve à l’identique chez l’homme. Les auteurs ne savent pas si les molécules identifiées, tels les flavonoïdes, seront également en cause chez les humains. Mais le concept général semble adaptable, estiment les chercheurs.

Auteur : pour Huffington Post

* Publication dans Nature 24 novembre 2016

Lire aussi : Weight regaining, From statistics and behaviors to physiology and metabolism, 2015[:en]Following a successful diet, many people are dismayed to find their weight rebounding – an all-too-common phenomenon termed “recurrent” or “yo-yo” obesity. Worse still, the vast majority of recurrently obese individuals not only rebound to their pre-dieting weight but also gain more weight with each dieting cycle. During each round of dieting-and-weight-regain, their proportion of body fat increases, and so does the risk of developing the manifestations of metabolic syndrome, including adult-onset diabetes, fatty liver and other obesity-related diseases.

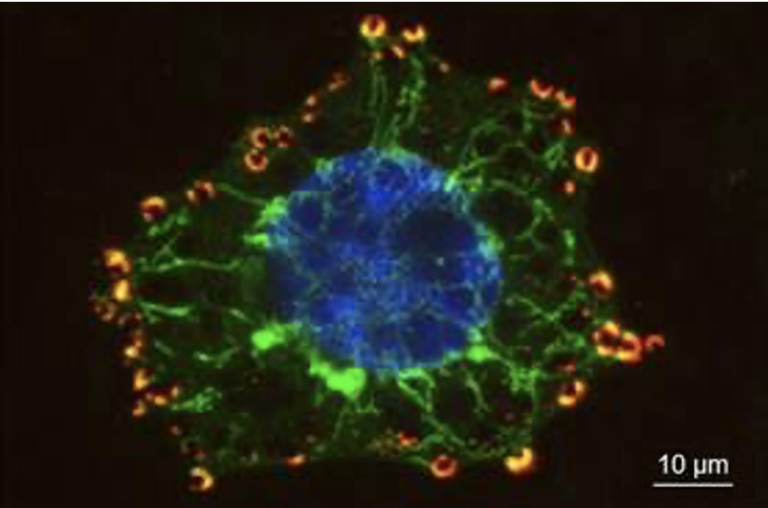

As recently reported in Nature, researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science have shown in mice that intestinal microbes – collectively termed the gut microbiome – play an unexpectedly important role in exacerbated post-dieting weight gain, and that this common phenomenon may in the future be prevented or treated by altering the composition or function of the microbiome.

The study was performed by research teams headed by Dr. Eran Elinav of the Immunology Department and Prof. Eran Segal of the Computer Science and Applied Mathematics Department. The researchers found that after a cycle of gaining and losing weight, all the mice’s body systems fully reverted to normal – except the microbiome. For about six months after losing weight, post-obese mice retained an abnormal “obese” microbiome.

“We’ve shown in obese mice that following successful dieting and weight loss, the microbiome retains a ‘memory’ of previous obesity,” says Elinav. “This persistent microbiome accelerated the regaining of weight when the mice were put back on a high-calorie diet or ate regular food in excessive amounts.” Segal elaborates: “By conducting a detailed functional analysis of the microbiome, we’ve developed potential therapeutic approaches to alleviating its impact on weight regain.”

The study was led by Christoph Thaiss, a Ph.D. student in Elinav’s lab. Thaiss collaborated with Master’s student Shlomik Itav of Elinav’s lab, Daphna Rothschild, a Ph.D. student of Segal’s lab, as well as with other scientists from Weizmann and elsewhere.

In a series of experiments, the scientists demonstrated that the makeup of the “obese” microbiome was a major driver of accelerated post-dieting weight gain. For example, when the researchers depleted the intestinal microbes in mice by giving them broad-spectrum antibiotics, the exaggerated post-diet weight gain was eliminated. In another experiment, when intestinal microbes from mice with a history of obesity were introduced into germ-free mice (which, by definition, carry no microbiome of their own), their weight gain was accelerated upon feeding with a high-calorie diet, compared to germ-free mice that had received an implant of intestinal microbes from mice with no history of weight gain.

Next, the scientists developed a machine-learning algorithm, based on hundreds of individualized microbiome parameters, which successfully and accurately predicted the rate of weight regain in each mouse, based on the characteristics of its microbiome after weight gain and successful dieting. Furthermore, by combining genomic and metabolic approaches, they then identified two molecules driving the impact of the microbiome on regaining weight. These molecules – belonging to the class of organic chemicals called flavonoids that are obtained through eating certain vegetables – are rapidly degraded by the “post-dieting” microbiome, so that the levels of these molecules in post-dieting mice are significantly lower than those in mice with no history of obesity. The researchers found that under normal circumstances, these two flavonoids promote energy expenditure during fat metabolism. Low levels of these flavonoids in weight cycling prevented this fat-derived energy release, causing the post-dieting mice to accumulate extra fat when they were returned to a high-calorie diet.

Finally, the researchers used these insights to develop new proof-of-concept treatments for recurrent obesity. First, they implanted formerly obese mice with gut microbes from mice that had never been obese. This fecal microbiome transplantation erased the “memory” of obesity in these mice when they were re-exposed to a high-calorie diet, preventing excessive recurrent obesity.

Next, the scientists used an approach that is likely to be more unobjectionable to humans: They supplemented post-dieting mice with flavonoids added to their drinking water. This brought their flavonoid levels, and thus their energy expenditure, back to normal levels. As a result, even on return to a high-calorie diet, the mice did not experience accelerated weight gain. Segal said: “We call this approach ‘post-biotic’ intervention. In contrast to probiotics, which introduce helpful microbes into the intestines, we are not introducing the microbes themselves but substances affected by the microbiome, which might prove to be more safe and effective.”

Recurrent obesity is an epidemic of massive proportions, in every meaning of the word. “Obesity affects nearly half of the world’s adult population, and predisposes people to common life-risking complications such as adult-onset diabetes and heart disease,” says Elinav. “If the results of our mouse studies are found to be applicable to humans, they may help diagnose and treat recurrent obesity, and this, in turn, may help alleviate the obesity epidemic.”

Also taking part in the study were Mariska Meijer, Maayan Levy, Claudia Moresi, Lenka Dohnalova, Sofia Braverman, Shachar Rozin, Dr. Mally Dori-Bachash and Staff Scientist Hagit Shapiro of the Immunology Department, Staff Scientists Drs. Yael Kuperman and Inbal Biton, and Prof. Alon Harmelin of the Veterinary Resources Department, and Dr. Sergey Malitsky and Prof. Asaph Aharoni of the Plant and Environmental Sciences Department – all of the Weizmann Institute of Science, as well as Prof. Arieh Gertler of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Prof. Zamir Halpern of the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center.

The Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, is one of the world’s top-ranking multidisciplinary research institutions. Noted for its wide-ranging exploration of the natural and exact sciences, the Institute is home to scientists, students, technicians and supporting staff. Institute research efforts include the search for new ways of fighting disease and hunger, examining leading questions in mathematics and computer science, probing the physics of matter and the universe, creating novel materials and developing new strategies for protecting the environment.[:]