Institut Weizmann (Israël) : les tempêtes de sable peuvent charrier des gènes d'antibiorésistance

[:fr]

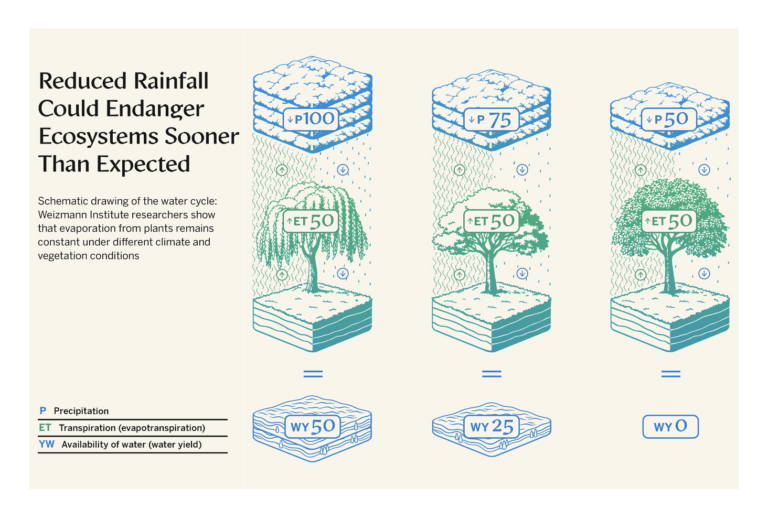

Les dérèglements climatiques provoqués par l’homme peuvent changer considérablement la composition des tempêtes de sable, engendrant des évolutions qui restent pour le moment inconnues. C’est la conclusion de l’étude menée par des chercheurs israéliens de l’institut Weizmann des Sciences.

Israël est fréquemment balayé par des tempêtes de sable provenant du Néguev ou de pays avoisinants comme la Syrie ou l’Egypte. Ces tempêtes transportent avec elles de nombreux micro-organismes présents dans les sols (bactéries, champignons, etc.) ainsi que bon nombre de particules (métaux, minéraux, etc.). Les tempêtes de sable transportent avec elles de nombreux agents pathogènes : plantes, pollens, bactéries, champignons. Cet ensemble d’entités peut jouer un rôle important et néfaste pour la biosphère et l’atmosphère. La composition des tempêtes de sable dépend fortement de leurs origines. Ainsi, la composition de celles provenant du Sahara est très différente de celles du désert syrien ou de l’Arabie saoudite.

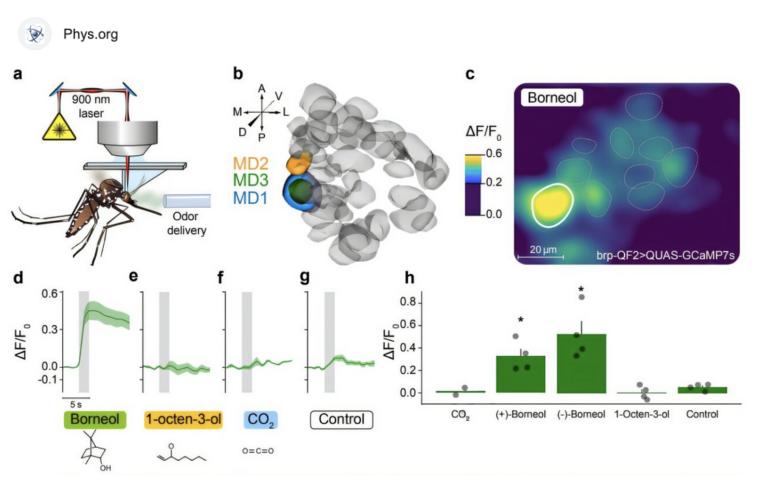

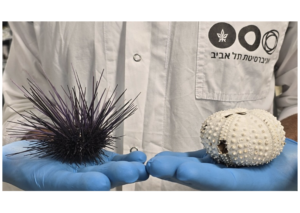

Certaines bactéries présentes dans les tempêtes de sable s’avèrent être des agents pathogènes pour l’homme et peuvent avoir un impact négatif sur l’environnement. Le Pr Yinon Rudich et son équipe à l’Institut Weizmann ont caractérisé le microbiote des tempêtes de sable, en établissant des cartes des différentes bactéries présentes durant les tempêtes, ainsi que leurs caractéristiques génétiques.

L’une des questions les plus brûlantes de notre société est la résistance aux antibiotiques. Concernant cette résistance, l’Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS) écrit : « La résistance aux antibiotiques constitue aujourd’hui l’une des plus graves menaces pesant sur la santé mondiale, la sécurité alimentaire et le développement ». Elle affirme que la planète se dirige vers « une ère post-antibiotique, dans laquelle les infections courantes pourront recommencer à tuer ». Dans une enquête publiée en mai 2016, l’économiste Jim O’Neill affirme que, durant les deux dernières années, la résistance aux antibiotiques aurait causé un million de morts par an, nombre qui devrait être multiplié par dix dans les trente prochaines années.

Les bactéries transportées par les tempêtes de sable peuvent elles aussi contenir des gènes de résistance aux antibiotiques. Le premier résultat obtenu par l’équipe de l’institut Weizmann montre une forte corrélation de la concentration et de la diversité des bactéries dans l’air avec la présence de tempêtes de sable. Ainsi, les personnes à l’extérieur durant ces tempêtes sont bien plus exposées aux bactéries. Il y a donc intérêt de se questionner sur la surreprésentation des bactéries dans l’atmosphère durant les tempêtes de sable.

Les chercheurs et chercheuses ont cartographié les résistances aux antibiotiques parmi les populations bactériennes présentes dans l’air. Cette résistance s’expliquerait par deux facteurs. D’une part, les bactéries peuvent contenir des résistances naturelles, notamment celles des bactéries provenant du sol. D’autre part, la surutilisation des antibiotiques dans l’exploitation animale crée elle aussi de très nombreuses résistances. Parmi les tempêtes testées, les chercheur.s.es ont retrouvé ces gènes de résistance aux antibiotiques lors de tempêtes en provenance d’Afrique et d’Arabie saoudite. Cependant, l’étude montre aussi que cette contribution restait minoritaire, comparée aux résistances introduites artificiellement par l’homme.

Les scientifiques concluent en affirmant que l’étude réalisée en nécessite une autre plus approfondie sur le caractère pathogène des bactéries qui survivent dans les tempêtes.

Auteur : Samuel Cousin, post-doctorant à l’Institut Weizmann pour le BVST

Publication dans Environmental Science & Technology, avril 2017

Sources : Centre d’information de l’OMS et Review on Antimicrobial Resistance

[:en]Israel is subjected to sand and dust storms from several directions: northeast from the Sahara, northwest from Saudi Arabia and southwest from the desert regions of Syria. The airborne dust carried in these storms affects the health of people and ecosystems alike. New research at the Weizmann Institute of Science suggests that part of the effect might not be in the particles of dust but rather in bacteria that cling to them, traveling many kilometers in the air with the storms.

Some of these bacteria might be pathogenic – harmful to us or the environment – and a few of them also carry genes for antibiotic resistance. Others may induce ecosystem functions such as nitrogen fixation. Prof. Yinon Rudich and his research group, including postdoctoral fellow Dr. Daniela Gat and former research student Yinon Mazar, in Weizmann’s Earth and Planetary Sciences Department investigated the genetics of the windborne bacteria arriving along with the dust.

“In essence, we investigated the microbiome of windborne dust,” says Rudich. “The microbiome of a dust storm originating in the Sahara is different from one blowing in from the Saudi or Syrian deserts, and we can see the fit between the bacterial population and the environmental conditions existing in each area.”

The researchers found that during a dust storm the concentration of bacteria and the number of bacterial species present in the atmosphere rise sharply, so people walking outdoors in these storms are exposed to many more bacteria than usual.

Rudich and his team then explored the genes in these bacteria, checking for antibiotic resistance – a trait that can arise owing to elevated use of antibiotics but also naturally, especially in soil bacteria. Antibiotic resistance has been defined by the World Health Organization as one of the primary global health challenges of the twenty-first century, and its main driver is the overuse of antibiotics. But bacteria can pass on the genes for antibiotic resistance, so any source of resistance is concerning. How many different genes for antibiotic resistance come to Israel from the various dust storms, and how prevalent are these genes?

Rudich says that the study enabled the researchers to identify a “signature” for each source of bacteria based on the prevalence of antibiotic resistant genes, which revealed whether the genes were local or imported from distant deserts. “We found that as more ‘mixing’ occurs between local dust and that which comes from far off, the lower the contribution of the imported antibiotic resistance genes.” In other words, antibiotic resistance coming from Africa or Saudi Arabia is still a very minor threat compared to that caused and spread by human activity, especially animal husbandry. Also participating in this research were Dr. Eddie Cytryn of the Volcani Center and Prof. Yigal Erel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

City air not set to improve

Urban air pollution is attributed, to a large extent, to emissions from transportation. Prof. Rudich and Staff Scientist Dr. Michal Pardo-Levin ask how these sources contribute to air pollution. Their findings show that pollution that does not come from the combustion engine but rather is released from the friction of the vehicle’s tires on the road and from braking systems can lead to serious health effects upon inhalation. That means that even if we manage to significantly reduce our cars’ tailpipe emissions, city air will still be polluted, to a large extent, with these other substances. And since the friction of tires and brakes are necessary for driving, reducing their emissions could be much harder.

Source Weizmann[:]