Weizmann (Israël) régénère des cellules cardiaques chez la souris

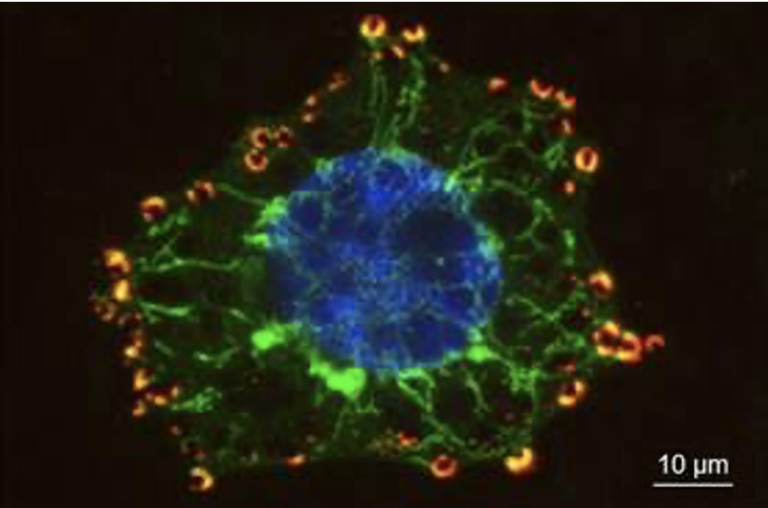

[:fr]Des recherches conduites à l’Institut Weizmann des sciences ont amené des cellules cardiaques de souris à faire marche arrière pour leur permettre de se renouveler. Cette recherche permet, d’une part, de mieux comprendre pourquoi le cœur des mammifères ne peut se régénérer, et montre d’autre part qu’il y a une possibilité, chez la souris adulte, d’éviter ce destin.

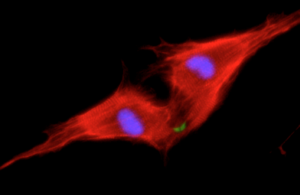

… Cette recherche sur le processus de régénération au moyen d’imagerie en temps réel et des études moléculaires ont révélé que les cardiomyocytes se ‘dé-différencient’, ce qui signifie qu’ils ramènent à une forme antérieure quelque chose qui se trouve à mi-chemin entre une cellule embryonnaire et une cellule adulte, qui est dès lors capable de se diviser et de se différencier en nouvelles cellules cardiaques. En d’autres mots, les récepteurs ERBB2 ont fait faire aux cellules un pas en arrière vers une forme embryonnaire, et ensuite l’arrêt de leur activité, a activé le processus de régénération.

En poursuivant leurs travaux, le Pr Tzahor et son équipe ont commencé à tracer la voie : celle des autres protéines qui répondent au message de NRG1 dans la cellule. Le docteur Gabriele D’Uva explique : « ERBB2 est clairement à la tête de la chaîne. Nous avons montré qu’il peut de lui-même induire une régénération cardiaque. Mais comprendre les rôles des autres protéines dans la chaîne peut nous diriger vers de nouvelles cibles médicamenteuses pour le traitement des maladies cardiaques »…

Publication dans Nature Cell Biology, 23 avril 2015[:en]Weizmann Institute research gets mouse heart cells to take a step backwards so they can be renewed. When a heart attack strikes, heart muscle cells die and scar tissue forms, paving the way for heart failure. Cardiovascular diseases are a major cause of death worldwide, in part because the cells in our most vital organ do not get renewed. As opposed to blood, hair or skin cells that can renew themselves throughout life, our heart cells cease to divide shortly after birth, and there is very little renewal in adulthood. New research at the Weizmann Institute of Science provides insight into the question of why the mammalian heart fails to regenerate, on one hand, and demonstrated, in adult mice, the possibility of turning back this fate. This research appeared in Nature Cell Biology.

Dr. Gabriele D’Uva, a postdoctoral fellow in the research group of Prof. Eldad Tzahor, wanted to know exactly how NRG1 and ERBB2 are involved in heart regeneration. In mice, new heart muscle cells can be added up to a week after birth; newborn mice can regenerate damaged hearts, while seven-day-old mice already cannot. D’Uva and research student Alla Aharonov observed that heart muscle cells called cardiomyocytes that were treated with NRG1 continued to proliferate on the day of birth; but the effect dropped dramatically within a week, even with ample amounts of NRG1. Further investigation showed that the difference between a day and a week was in the amount of ERBB2 on the cardiomyocyte membranes.

Tzahor points out that clinical trials of patients receiving the NRG1 treatment might not be overly successful if ERBB2 levels are not boosted as well. He and his team plan to continue researching this signaling pathway to suggest ways of improving the process, which may, in the future, point to ways of renewing heart cells. Because this pathway is also involved in cancer, well-grounded studies will be needed to understand exactly how to direct the cardiomyocyte renewal signal at the right place, the right time and in the right amount. “Much more research will be required to see if this principle could be applied to the human heart, but our findings are proof that it may be possible,” he says.

Publication in Nature Cell Biology, April, 23 2015[:]