Weizmann (Israël) : un microscope à ultra-haute résolution grâce à la physique quantique et les lasers

[:fr]

Une équipe de chercheurs menée par le Prof. Yaron Silberberg et le Prof. Dan Oron de l’Institut Weizmann a développé une nouvelle technique de microscopie dite de super-résolution, basée sur la mécanique quantique. Les techniques de super-résolution permettent d’obtenir l’image d’objets qui ne peuvent pas être distingués avec les microscopes standards que l’on trouve dans les collèges et les lycées. Le développement de ces techniques a complètement bouleversé les domaines de l’imagerie médicale et de la biologie. Les chercheurs de l’Institut Weizmann viennent d’ajouter leur pierre à l’édifice.

A la fin du 19ème siècle, le physicien allemand Ernst Abbe a déterminé que l’image d’un point par la lentille la plus parfaite ou bien par l’objectif de microscope le plus parfait ne sera jamais un point mais plutôt une tâche diffuse, dont la taille limite est dictée par les lois de la physique. Il est important de comprendre qu’un microscope, même le plus basique, permet de collecter la lumière d’objets extrêmement petits. Cela veut dire qu’à l’aide d’un objectif de microscope relativement simple, on pourrait collecter la lumière émise par un seul atome (dont le rayon est d’environ 10-11 m) et on observerait alors sur notre caméra une tâche diffuse indiquant la présence de l’atome. En revanche, si deux atomes qui émettent de la lumière sont très proches, on ne pourrait pas distinguer l’un de l’autre. La distance minimale entre les deux atomes en deçà de laquelle on ne pourrait plus les distinguer est appelée la résolution d’un microscope. En règle générale, un microscope optique ne peut distinguer deux objets séparés de moins de la moitié d’une longueur d’onde de la lumière utilisée pour éclairer l’objet. Cela correspond en pratique à une limite de résolution de l’ordre de 200 nanomètres si la lumière utilisée est bleue.

Lorsque Ernst Abbe a énoncé sa limite, il a émis plusieurs hypothèses quant à la façon dont le microscope utilisé fonctionne. Ses hypothèses étaient basées sur le bon sens et il aura fallu attendre plus d’un siècle pour que Stefan Hell parvienne à contourner l’une des hypothèses d’Abbe, inventant alors le premier microscope dit de super-résolution. Cette invention lui a valu, ainsi qu’à deux autres physiciens, le prix Nobel de chimie en 2014. Ces nouvelles techniques de microscopie, dont les principales sont appelées STED et PALM, permettent de distinguer deux objets séparés de l’ordre de quelques nanomètres et ont complètement bouleversé les domaines de l’imagerie médicale et de la biologie.

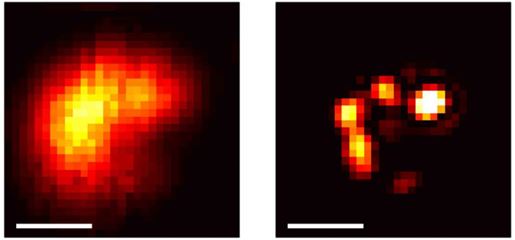

Contrairement aux techniques citées ci-dessus, des chercheurs de l’Institut Weizmann ont eu pour idée d’utiliser la nature quantique de la lumière afin de passer outre la limite d’Abbe. L’équipe dirigée par les professeurs Dan Oron et Yaron Silberberg a réussi cet exploit en observant des photons uniques émis par des molécules uniques. En appliquant les lois de la mécanique quantique et en regardant les temps d’arrivée des photons, les chercheurs sont parvenus à observer des objets séparés de l’ordre de 80 nanomètres. Son originalité et le fait qu’il n’est nécessaire de modifier légèrement des microscopes disponibles dans le commerce pour l’appliquer font de cette nouvelle technique un incontournable du domaine.

Publication dans Nature 17 décembre 2018

Rédacteur : Arnaud Courvoisier, doctorant à l’Institut Weizmann pour le BVST

[:en]

Ever since Ernst Abbe set a lower limit to the size of things that can be seen under a microscope, people have been looking for ways to surpass that limit. While electron microscopes and several new types of microscopy have since broken through the limit, a method developed by physicists at the Weizmann Institute of Science suggests a new way of going below the limit with a standard optical microscope.

Abbe was a physicist and managing partner in Zeiss Optical Works – a position offered to him by the founder of the company, Carl Zeiss. Abbe set his limit in 1873, when he stated that even the most perfectly ground lenses would not be able to distinguish objects smaller than half the length of a wave of visible light. In practice this corresponds to a resolution limit of about 200 nanometers.

It would take some 60 years for the arrival of a microscope that could break the optical limit. Ernst Ruska and his doctoral adviser Max Knoll invented the first electron microscope in 1933. This microscope used an electron beam instead of light. Because the wavelength of an electron is much less than the length of a visible light wave, the beam enabled them to see things that are up to 2,000 times smaller than what can be observed with a standard optical microscope. The drawback to electron microscopes is that samples must be fixed, so living things cannot be imaged under these microscopes. It would take some 60 years for the arrival of a microscope that could break the optical limit.

Almost 70 years after this, in 1999, Stefan Hell unveiled a new type of microscope, called STED (for stimulated emission depletion), which presented a completely new way of surpassing Abbe’s limit. In STED, one laser beam excites an electron in a molecule of the material under observation. When excited, the electron emits a photon – a particle of light – in a process known as fluorescence. In Hell’s microscope, a second laser douses the fluorescence, and the lasers then quickly scan the sample, making it possible to observe objects just a few nanometers in size; they can distinguish, for example, active proteins in biological systems.

An alternative method, known as PALM (photoactivated light microscopy), followed on the heels of STED. This method relies on light-emitting molecules that are also activated by light. The developers of PALM, Eric Betzig and William Moerner shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Hell in 2014, for breaking Abbe’s limit and providing new super-high-resolution microscopy for research labs around the world.

Sensitive to single photons

Profs. Yaron Silberberg and Dan Oron and their colleagues in the Physics of Complex Systems Department at the Weizmann Institute of Science thought that quantum physics might offer another way around Abbe’s limit. (Abbe, of course, did not have the benefit of quantum theory, which only appeared on the scene several decades later.) Specifically, in quantum mechanics, any molecule or nano-sized particle that is excited – for example, by shining a laser beam on it – can emit one, and only one photon. Their idea was to “photograph” the process of photon emission. Of course this process happens so quickly that even the fastest camera – one that is sensitive to single photons – still cannot capture it as it happens.

The Institute researchers swapped the standard microscope camera for a system of ultra-fast detectors that are so sensitive, they can pick up the emission of a single photon; and they installed this on a scanning optical microscope (one based on the confocal microscope invented in 1957 by Marvin Minsky). Their calculations showed that this system should break Abbe’s limit. And, indeed, an experiment with such a system succeeded in observing objects 2 ½ times smaller than those at Abbe’s limit. The scientists say their calculations suggest that further calibration and experimentation should get the limit of the combined system even lower, to around four times smaller than the size set by Abbe.

[:]