JNF and Migal Institute (Israel): Speeding Tree Growth with Fungi

Israeli researchers have found a natural and symbiotic way to expedite the growth of pine trees by involving edible fungi mushrooms in their early years of growth. Throughout human history, mushrooms have played an integral role in many early cultures around the world. Early Greek, Roman, and Chinese cultures all recognized their innate nutritional value and incorporated them into their own respective cuisines. Through our modern understanding of science today, we specifically know the reason why mushrooms were so revered.

Beyond the fact that they are absent of cholesterol and low in calories, carbohydrates, fat, and sodium, they are packed with many important nutrients that have been linked to providing many important health benefits. Selenium, potassium, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin D, various proteins, fiber, and the bioactive compounds within mushrooms effectively work to boost our immune systems and are used to help treat and prevent many infamous diseases and ailments like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, cancer, and hypertension.

The benefits of edible mushrooms, however, are not solely limited to humans according to a new Israeli study, which found that trees grew faster when they were infected with certain kinds of edible mushrooms.

A Good Infection

The new study was conducted in collaboration with researchers from the JNF and MIGAL – the Galilee Research Institute. “The JNF is trying very hard to encourage the phenomenon of edible forests and wants to create forests with mycorrhizal edible mushrooms that are interesting to collect,” says Dr. Ofer Danay, director of mushrooms and truffle research at MIGAL and co-author of the new study.

“Certain species of pines, especially stone pine (Pinus pinea), do not survive in calcareous soils, which are the most common type of soil in Israel,” says Danay. “Therefore, attempts are now being made to ‘help’ the stone pine cope with these difficulties by infecting it with mycorrhizal fungi as a means of increasing its share in pine groves, mainly because it is less susceptible to pine pests whose larva harms trees and potentially cause medical problems for humans.”

Beyond that, increasing the amount of fungus in the soil may help also help in the fight against the climate crisis. “According to research by Dr. Tamir Klein of the Weizmann Institute, mycorrhizal fungi reduce the loss of carbon fixed in the soil and reduces the amount of carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere,” explains Danay.

Beyond the pleasures of the foraging experience and the multiple flavor profiles many edible fungi mushrooms have, misidentifying one can have serious and potentially fatal consequences.

“Every year there are reports of poisoning due to incorrect identification and collection of fungi, which can even cause death,” says Danay. He emphasizes the importance of caution and diligence when collecting. “Whoever collects mushrooms should be completely familiar with the mushroom he or she is picking and be sure of its identification. There are no rules of thumb on the subject, so if there is any doubt, you should avoid picking and eating the mushroom altogether.”

Another important point is the need to avoid over-collecting mushrooms because this can impair their ability to recover and reproduce. “They need to be harvested in proportion—in small amounts—so that the fungi can continue to grow and spread themselves,” says Danay. “I sometimes get photos of people coming back from collecting with buckets full of mushrooms and leaving behind a bare ground. It’s a wrong, and it’s a problematic situation.”

Preserving the mycorrhizal edible mushrooms that grow in forests is especially important today because of the precarious situation we have placed our climate. “In recent years, there has been a decrease in the abundance and diversity of these fungi species in nature due to because of over-collection and the climate crisis,” says Danay. “It’s important to preserve the biodiversity of the fungus for the benefit of the forest’s health as well as our own,” he concludes.

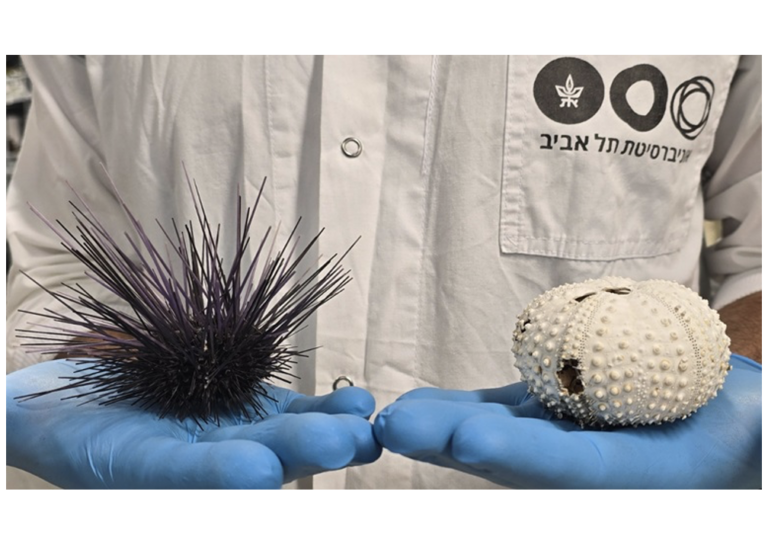

With the spores of two popular edible fungi, Suillus collinitus and Lactarius deliciosus, the researchers infected about 120 sprouts from three different species of trees: stone pine (Pinus pinea), Calabrian Pine (Pinus brutia), and Jerusalem Pine—also commonly referred to as Aleppo Pine (Pinus halepensis). They examined how fungal infection affects the trees during the first two years of their lives before they are transferred to a field for planting.

“As early as the nursery stage, we found that the trees infected with mycorrhizal fungi developed better than the trees from the control group, which were not infected with the fungus,” says Danay. The results of the study showed the infected young trees of the three sampled pine species were taller and their stem (trunk) diameters were wider. The greatest effect was seen in the Jerusalem pine species, which were 180% larger than the control group. This was followed by Calabrian Pine, which showed a 160% improvement in height and diameter, and then stone pine, which exhibited a 124% growth increase. Stimulated growth to this degree bodes well for reforestation and afforestation efforts.

A Reciprocal Relationship

So, why do fungus-infected trees grow better? The answer lies in the workings of symbiosis, or the mutual beneficial relationship between two organisms. In this case, the fungus, which densely envelops the tree’s roots, helps deliver water and essential nutrients like phosphorus, iron, and magnesium from the soil for the tree’s early development. In return, the fungus can absorb the nutrients and sugars it needs to build up its body, which the tree produces through photosynthesis.

Due to various fungi species’ presence in soil environments, tree roots become regularly and naturally entangled with mycorrhizal fungi. Through the use of molecular methods, Danay believes it’s worthwhile to identify which mycorrhizal fungi exist in the soil so as to better choose the species of trees that can best “host” them to ensure rapid development and survival of the forest trees. “This will also make it possible to preserve the mushrooms, some of which can be used for food and some of which are even in danger of extinction.”

It should be noted that despite the chance that trees may eventually become infected with the fungus “naturally,” there is a benefit in infecting the sprouts while they are in the nursery. “We anticipate that infected trees will reach a size that will allow them to start and yield multiplicative bodies of the edible mycorrhizal fungi earlier than the current situation,” he says.

Don’t Take Too Many

Beyond the pleasures of the foraging experience and the multiple flavor profiles many edible fungi mushrooms have, misidentifying one can have serious and potentially fatal consequences.

“Every year there are reports of poisoning due to incorrect identification and collection of fungi, which can even cause death,” says Danay. He emphasizes the importance of caution and diligence when collecting. “Whoever collects mushrooms should be completely familiar with the mushroom he or she is picking and be sure of its identification. There are no rules of thumb on the subject, so if there is any doubt, you should avoid picking and eating the mushroom altogether.”

Another important point is the need to avoid over-collecting mushrooms because this can impair their ability to recover and reproduce. “They need to be harvested in proportion—in small amounts—so that the fungi can continue to grow and spread themselves,” says Danay. “I sometimes get photos of people coming back from collecting with buckets full of mushrooms and leaving behind a bare ground. It’s a wrong, and it’s a problematic situation.”

Preserving the mycorrhizal edible mushrooms that grow in forests is especially important today because of the precarious situation we have placed our climate. “In recent years, there has been a decrease in the abundance and diversity of these fungi species in nature due to because of over-collection and the climate crisis,” says Danay. “It’s important to preserve the biodiversity of the fungus for the benefit of the forest’s health as well as our own,” he concludes.

Publication dans yaar magazine

Racheli Wacks for Zavit