Weizmann (Israel): New research reveals the comparative environmental costs of livestock-based foods

We are told that eating beef is bad for the environment, but do we know its real cost? Are the other animal or animal-derived foods better or worse? New research at the Weizmann Institute of Science, conducted in collaboration with scientists in the US, compared the environmental costs of various foods and came up with some surprisingly clear results. The findings, which appear today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), will hopefully not only inform individual dietary choices, but those of governmental agencies that set agricultural and marketing policies.

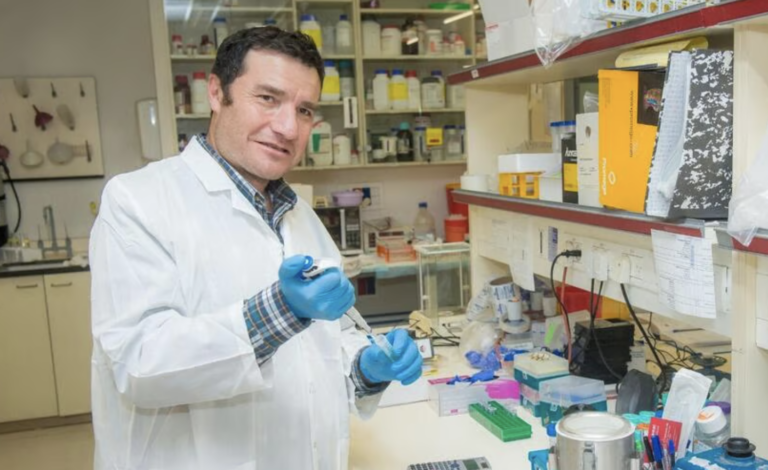

Dr. Ron Milo of the Institute’s Plant Sciences Department, together with his research student Alon Shepon, in collaboration with Tamar Makov of Yale University and Dr. Gidon Eshel in New York, asked which types of animal based-food should one consume, environmentally speaking. Though many studies have addressed parts of the issue, none has done a thorough, comparative study that gives a multi-perspective picture of the environmental costs of food derived from animals.

The team looked at the five main sources of protein in the American diet: dairy, beef, poultry, pork and eggs. Their idea was to calculate the environmental inputs – the costs – per nutritional unit: a calorie or gram of protein. The main challenge the team faced was to devise accurate, faithful input values. For example, cattle grazing on arid land in the western half of the US use enormous amounts of land, but relatively little irrigation water. Cattle in feedlots, on the other hand, eat mostly corn, which requires less land, but much more irrigation and nitrogen fertilizer. The researchers needed to account for these differences, but determine aggregate figures that reflect current practices and thus approximate the true environmental cost for each food item.

The inputs the researchers employed came from the US Department of Agriculture databases, among other resources. Using the US for this study is ideal, says Milo, because much of the data quality is high, enabling them to include, for example, figures on import-export imbalances that add to the cost. The environmental inputs the team considered included land use, irrigation water, greenhouse gas emissions, and nitrogen fertilizer use. Each of these costs is a complex environmental system. For example, land use, in addition to tying up this valuable resource in agriculture, is the main cause of biodiversity loss. Nitrogen fertilizer creates water pollution in natural waterways.

When the numbers were in, including those for the environmental costs of different kinds of feed (pasture, roughage such as hay, and concentrates such as corn), the team developed equations that yielded values for the environmental cost – per calorie and then per unit of protein, for each food.

The calculations showed that the biggest culprit, by far, is beef. That was no surprise, say Milo and Shepon. The surprise was in the size of the gap: In total, eating beef is more costly to the environment by an order of magnitude – about ten times on average – than other animal-derived foods, including pork and poultry. Cattle require on average 28 times more land and 11 times more irrigation water, are responsible for releasing 5 times more greenhouse gases, and consume 6 times as much nitrogen, as eggs or poultry. Poultry, pork, eggs and dairy all came out fairly similar. That was also surprising, because dairy production is often thought to be relatively environmentally benign. But the research shows that the price of irrigating and fertilizing the crops fed to milk cows – as well as the relative inefficiency of cows in comparison to other livestock – jacks up the cost significantly.

Milo believes that this study could have a number of implications. In addition to helping individuals make better choices about their diet, it should hopefully help inform agricultural policy. And the tool the team has created for analyzing the environmental costs of agriculture can be expanded and refined to be applied, for example, to understanding the relative cost of plant-based diets, or those of other nations. In addition to comparisons, it can point to areas that might be improved. Models based on this study can help policy makers decide how to better ensure food security through sustainable practices.

Dr. Ron Milo’s research is supported by the Mary and Tom Beck-Canadian Center for Alternative Energy Research; the Lerner Family Plant Science Research Endowment Fund; the European Research Council; the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; Dana and Yossie Hollander, Israel; the Jacob and Charlotte Lehrman Foundation; the Larson Charitable Foundation; the Wolfson Family Charitable Trust; Charles Rothschild, Brazil; Selmo Nissenbaum, Brazil; and the estate of David Arthur Barton. Dr. Milo is the incumbent of the Anna and Maurice Boukstein Career Development Chair in Perpetuity.