University of Haifa: Plastic Waste from Jerusalem’s Runoff Has Accumulated in the Dead Sea Since 2000

A University of Haifa analysis of the Dead Sea’s coastal terraces reveals a sharp rise in plastic accumulation originating from flash floods in the Kidron Stream; accelerated decomposition processes generating increasing quantities of microplastic; and waste trapped in sinkholes, leaving a lasting geological mark.

Haifa, Israel (Dec. 8, 2025) – A new study conducted at University of Haifa has, for the first time, documented two decades of plastic accumulation on the retreating coastal terraces of the Dead Sea—providing the first evidence of plastic pollution at the lowest point on Earth. The study, published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials, shows that a unique combination of flash floods, extreme salinity, and rapid drops in sea level has created a natural “archive” where plastic remnants originating in the Jerusalem area are preserved after reaching the Dead Sea coastline annually.

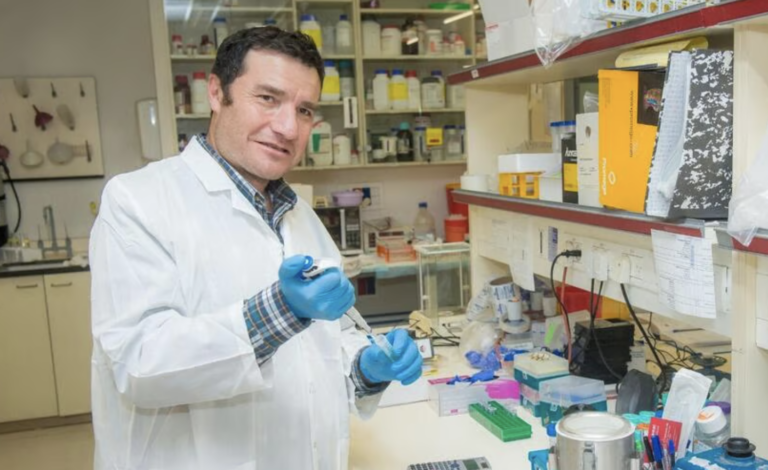

“When we arrived at the site, we saw not only a dramatic retreat of the coastline but also enormous amounts of plastic, including bags, toys, and even military equipment floating on the water’s surface. It was a jarring moment that made it clear to us how deep and severe the phenomenon is,” said Dr. Ákos Kalman of University of Haifa, one of the study’s authors.

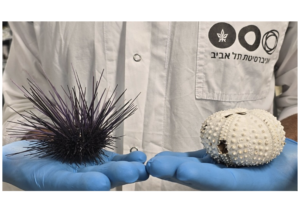

The Dead Sea—the world’s deepest hypersaline lake—has experienced rapid and continuous water-level decline over recent decades. The Kidron Stream, which drains extensive urban areas in Jerusalem, transports sediments, debris, and urban waste—including plastics—into the Dead Sea during short but powerful winter flash floods. Due to the high salinity and density of the Dead Sea, most plastic materials float and accumulate along the coastline, forming a series of coastal terraces that document the amount and type of waste reaching the area each year. The research team, which included Prof. Beverly Goodman-Tchernov, Prof. Michael Lazar, Dr. Ákos Kalman, Thomai Anagnostoudi, and Alyssa Pietraszek from the Charney School of Marine Sciences at University of Haifa, collaborated with researchers from Italy. They refer to these deposits as “plastic rings,” a striking visual and scientific marker of human impact.

In this study, the researchers examined coastal terraces formed between 2000 and 2021 at the junction of the Kidron Stream and the Dead Sea. They systematically collected all visible plastic items on each terrace and documented their weights, types, abrasion levels, and spatial distribution. They also collected sediment samples for microplastic analysis. In the laboratory, microplastic particles were separated from the sediments, filtered, counted, and photographed under a microscope. The particles were then analyzed using infrared spectroscopy, allowing researchers to identify polymer types and the chemical changes resulting from prolonged exposure to sun, high temperatures, and extreme erosion conditions. Concurrently, the team analyzed historical aerial photographs and satellite images to understand how shifts in coastal geomorphology and the stream’s flow path have influenced waste transport and accumulation over time.

The analysis shows that plastic input surged after 2000, with younger terraces containing hundreds of kilograms of waste. Projections indicate that a single future terrace could accumulate more than a ton of plastic by 2030. As plastics sit exposed on the region’s hyper-arid coast, intense solar radiation and high temperatures accelerate fragmentation, producing tens of thousands of microplastic particles per kilogram of sediment. According to the researchers, one kilogram of large visible plastic can disintegrate into approximately four thousand microplastic particles each year. If current trends continue, the accumulated plastic weight on a single terrace could approach one ton by 2030.

The study also found that some waste becomes trapped in the sinkholes and cracks forming along the retreating coastline—a process that embeds plastic into sediment layers and may create a lasting geological record of human activity in the area.

“The broad picture is clear: as the population grows, so does the volume of waste reaching the streams and ultimately the Dead Sea. The fact that most of the plastic floats and accumulates along the coast suggests that there is a window of opportunity to address it before it is buried and the situation becomes irreversible. The findings show that without addressing the source of the pollution, the waste will continue to drift to the coast, become trapped in sinkholes, and form sediment layers that will remain a permanent part of the region’s geological environment,” the researchers concluded.

Publication in Journal of Hazardous Materials