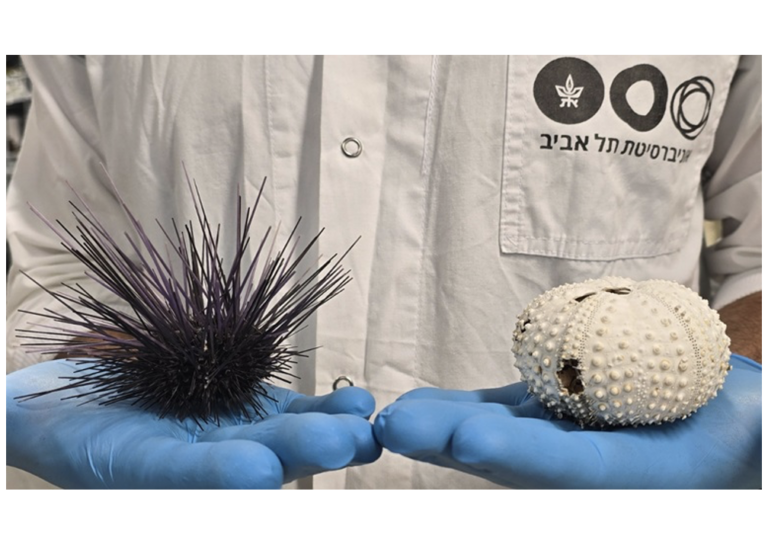

BGU (Israel): Geochemistry of Shells Can Be Used to Monitor Ocean Pollution

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences Prof. Sigal Abramovich has a mission. She wants to convince Israeli and global regulators to include regular monitoring of the geochemistry of a certain type of shell of marine organisms as an indicator of pollution in the ocean.

In a series of studies over the past three years, Abramovich and her team (Dr. Danna Titelboim, Nir Ben Eliahu, and Chen Kenigsberg, Sneha Manda, and Doron Pinko) and colleague Prof. Barak Herut from the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute and Dr. Ahuva Almogi-Labin from the Geological Survey of Israel have found that foraminifera found on the ocean floor store evidence of the pollution around them within their shell formation.

Coastal infrastructure makes the marine ecosystem susceptible to incidental industrial metal introduction that, even if relatively short-term, could stress local ecosystems or affect the water quality. Traditional monitoring methods are insensitive to these events, and thus better and more comprehensive monitoring methods are required.

Foraminifera are unicellular organisms that produce calcite shells directly from seawater. They are among the most ancient and abundant fossils and their calcite shells accumulate in mass quantities in oceanic sediments and thus become one of the most important components of sedimentary (carbonate) rocks. Their shells record the chemical and physical properties of their seawater, providing the basis for most climate research. This is the reason why foraminifera are considered one of the most important archives of ancient and modern oceans.

Foraminifera build their shells by sequential addition of chambers and each shell thus represents a natural monitoring sequence recording heavy metals in the ambient seawater over months. This chronological documentation of heavy metals in the seawater allows the recognition and quantification of short-term pollution events, and, since foraminifera are abundant, small and their shells are preserved after death, the monitoring can be carried out retroactively and at high spatial resolution.

“We have been able to quantify the amounts of heavy metals pollution injected by the brine discharge from desalination plants across the Mediterranean coast of Israel,” explains Prof. Abramovich. “Our research demonstrates the potential of using heavy metals anomalies in foraminiferal shells as a tool for detecting the industrial footprint of coastal facilities including areas that were considered clean nature reserves.”

She is working with an international network of oceanographers to encourage countries around the world to adopt regular foraminifera monitoring based on the methods developed in her lab.

Her research has been supported by the Israeli Ministry of Science through the BMBF-MOST program, by a GIF (German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development) grant and the Israel Science Foundation.

Relevant Articles:

1) PLOS ONE The effect of long-term brine discharge from desalination plants on benthic foraminifera Published: January 14, 2020

2) Biogeosciences Foraminiferal holobiont thermal tolerance under future warming – roommate problems or successful collaboration? Published: April 27, 2020

3) International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Shell Growth of Large Benthic Foraminifera under Heavy Metals Pollution: Implications for Geochemical Monitoring of Coastal Environments Published: May 25, 2020

4) Marine Environmental Research Epiphytic benthic foraminiferal preferences for macroalgal habitats: Implications for coastal warming Published: August 9, 2020

5) Biogeosciences Differential Sensitivity of a Symbiont‐Bearing Foraminifer to Seawater Carbonate Chemistry in a Decoupled DIC‐pH Experiment Published: August 21, 2021

6) Ecological Indicators Monitoring of heavy metals in seawater using single chamber foraminiferal sclerochronology Published: September 19, 2020

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) is the fastest growing research university in Israel. With 20,000 students, 4,000 staff and faculty members, and three campuses in Beer-Sheva, Sde Boker and Eilat, BGU is an agent of change, fulfilling the vision of David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s legendary first prime minister, who envisaged the future of Israel emerging from the Negev.

The University is at the heart of Beer-Sheva’s transformation into an innovation district, where leading multinational corporations and start-ups eagerly leverage BGU’s expertise to generate innovative R&D.

BGU effects change, locally, regionally and internationally. With faculties in Engineering Sciences; Health Sciences; Natural Sciences; Humanities and Social Sciences; Business and Management; and Desert Studies, the University is a recognized national and global leader in many fields, actively encouraging multi-disciplinary collaborations with government and industry, and nurturing entrepreneurship and innovation in all its forms.

BGU is also a university with a conscience, active both on the frontiers of science and in the community. Over a third of our students participate in one of the world’s most developed community action programs.

For more information, visit the BGU website.

Photo Caption: Sampling location adjacent to the Hadera Power Plant. Foraminifera are found in vast numbers attached tomacroalgae that cover the hard rock flats at very shallow water depths.

Photo Credit: Prof. Sigal Abramovich

Click on photo for high resolution version

This photo may only be used in the context of articles about this research study or Ben-Gurion University