Tel Aviv University and IIE: corals’ fluorescent colors are designed to serve as lure for their prey

It is a known fact that corals glow, even at a depth of 45 meters. Now, Tel Aviv University researchers have succeeded in proving for the first time, evidence that the corals’ fluorescent colors are designed to serve as lure for their prey.

A new Tel Aviv University study, in collaboration with the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, and the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat, has proven for the first time that the magical phenomenon in deep reefs in which corals display glowing colors (fluorescence) is intended to serve as a mechanism for attracting prey. The study shows that the marine animals on which corals prey recognize the fluorescent colors and are attracted to them.

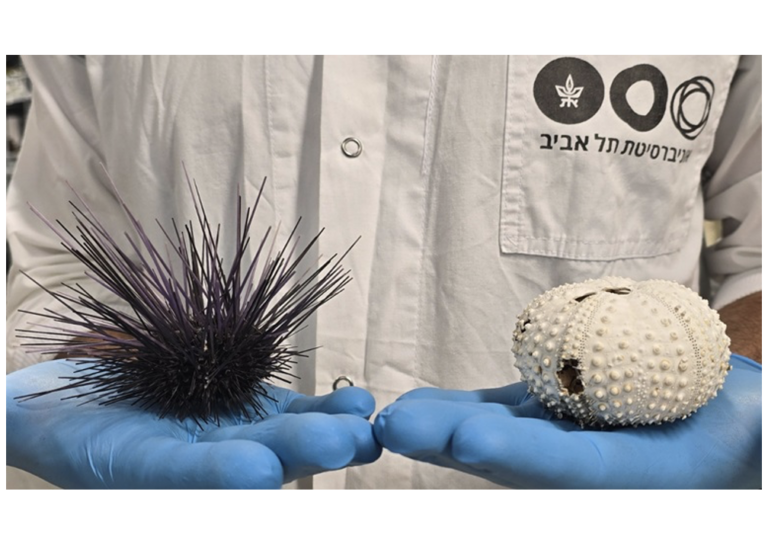

The study was led by Dr. Or Ben-Zvi, in collaboration with Yoav Lindemann and Dr. Gal Eyal, under the supervision of Prof. Yossi Loya from the School of Zoology and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University.

The researchers explain that for centuries, nature lovers and scientists have been fascinated by the fact that creatures in the sea are able to glow. The phenomenon is very common in reef-building corals, but its biological role has been the subject of constant debate. Over the years, a number of hypotheses have been tested, such as: Does this phenomenon protect against radiation? To optimize photosynthesis? An antioxidant activity? To protect against herbivores or to attract symbiotic algae to the corals? This latest study shows that the function of the corals’ fluorescence is actually to serve as lure for prey.

In the study, the researchers put their hypothesis to the test; to this end, they first sought to determine whether plankton (small organisms that drift in the sea along with the current) are attracted to fluorescence, both in the laboratory and at sea. Then, in the lab, the researchers quantified the predatory capabilities of mesophotic corals (corals that live between the shallow coral reef area and the deep, completely dark zone of the ocean), which exhibit different fluorescent appearances.

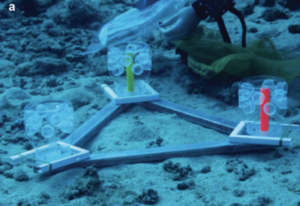

In order to test the planktons’ potential attraction to fluorescence, the researchers used, inter alia, the crustacean Artemia salina, which is used in many experiments as well as for food for corals. The researchers noted that when the crustaceans were given a choice between a green or orange fluorescent target versus a clear “control” target, they showed a significant preference for the fluorescent target.

Moreover, when the crustaceans were given a choice between two clear targets, its choices were observed to be randomly distributed in the experimental setup. In all of the laboratory experiments, the crustaceans vastly exhibited a preferred attraction toward a fluorescent signal. Similar results were presented when using a native crustacean from the Red Sea. However, unlike the crustaceans, fish that are not considered coral prey did not exhibit these trends, and rather avoided the fluorescent targets in general and the orange targets in particular.

In the second phase of the study, the experiment was carried out in the corals’ natural habitat, about 40 meters deep in the sea, where the fluorescent traps (both green and orange) attracted twice as many plankton as the clear trap. Dr. Or Ben-Zvi says, “We conducted an experiment in the depths of the sea in order to examine the possible attraction of diverse and natural collections of plankton to fluorescence, under the natural currents and light conditions that exist in deep water. Since fluorescence is ‘activated’ principally by blue light (the light of the depths of the sea), at these depths the fluorescence is naturally illuminated, and the data that emerged from the experiment were unequivocal, similar to the laboratory experiment.”

In the last part of the study, the researchers examined the predation rates of mesophotic corals that were collected at 45 m depth in the Gulf of Eilat, and found that corals that displayed green fluorescence enjoyed predation rates that were 25 percent higher than corals exhibiting yellow fluorescence.

Prof. Loya: “Many corals display a fluorescent color pattern that highlights their mouths or tentacle tips, a fact that supports the idea that fluorescence, like bioluminescence (the production of light by a chemical reaction), acts as a mechanism to attract prey. The study proves that the glowing and colorful appearance of corals can act as a lure to attract swimming plankton to ground-dwelling predators, such as corals, and especially in habitats where corals require other energy sources in addition or as a substitute for photosynthesis (sugar production by symbiotic algae inside the coral tissue using light energy).”

Dr. Ben-Zvi concludes: “Despite the gaps in the existing knowledge regarding the visual perception of fluorescence signals by plankton, the current study presents experimental evidence for the prey-luring role of fluorescence in corals. We suggest that this hypothesis, which we term the ‘light trap hypothesis’, may also apply to other fluorescent organisms in the sea, and that this phenomenon may play a greater role in marine ecosystems than previously thought.”

Publication in Nature June 2nd 2022