Génial ! Weizmann développe une trithérapie qui vient à bout du cancer du poumon

[:fr]Le cancer du poumon est la principale cause de mortalité liée au cancer dans le monde, il est responsable de 1,59 million de morts par an. Ceci est en partie dû au fait que le cancer récidive fréquemment à la suite de traitements efficaces au début. De plus, le cancer récurrent est souvent résistant à la chimiothérapie et aux autres drogues qui à l’origine entraînaient sa rémission. D’après une nouvelle étude menée par le Pr Yosef Yarden de l’Institut Weizmann, une nouvelle stratégie impliquant une approche articulée sur trois fronts, une trithérapie personnalisée, pourrait prévenir la réapparition d’une forme agressive de cancer du poumon.

« Ces recherches s’appuient sur plusieurs résultats surprenants obtenus au cours d’essais cliniques », dit Yarden. « Une catégorie de cancer du poumon relativement courante, qui porte une mutation précise du récepteur EGFR, un récepteur de la membrane cellulaire, peut-être traitée avec une sorte de médicament miracle. » Ce médicament empêche le signal de croissance d’entrer dans la cellule, ce qui empêche, à son tour, l’évolution et la propagation mortelle du cancer. Mais, au bout d’une année, ceux présentant cette mutation connaissent invariablement une nouvelle poussée cancéreuse, qui résulte, en général, d’une seconde mutation d’EGFR. Pour éviter cela, les chercheurs ont essayé d’administrer un autre médicament, un anticorps utilisé de nos jours pour traiter le cancer colorectal. Ce médicament empêche la transmission du signal de croissance en bloquant EGFR. Même si l’anticorps médicament aurait dû être capable de bloquer efficacement les récepteurs de croissance EGFR, y compris ceux issus de la seconde mutation, les essais cliniques de ce médicament sur le cancer du poumon n’ont pas eu les effets escomptés. « Ces observations allaient à l’encontre de tout ce que nous connaissions sur la façon dont les tumeurs développent des résistances », explique Yosef Yarden.

Mais comment les cellules cancéreuses font-elles pour contourner le blocage établi par un anticorps anti-EGFR ? Yosef Yarden et son étudiant Maicol Mancini, ont découvert ce qui arrive aux cellules cancéreuses lorsqu’elles sont exposées à cet anticorps bloqueur de récepteur.

« Le récepteur bloqué à des « frères », d’autres récepteurs qui peuvent monter au créneau pour faire le travail », dit Yosef Yarden. En effet, l’équipe a trouvé que, quand le récepteur principal (EGFR) était bloqué en continu, l’un des réseaux de communication cellulaire était détourné, provoquant l’apparition des frères sur la membrane cellulaire à la place du récepteur d’origine. Puisque l’anticorps, finement ajusté au premier récepteur, ne peut pas les bloquer, les cellules cancéreuses reprenaient, une fois de plus, leur activité. Les chercheurs ont découvert une chaine de communication protéique dans le nouveau réseau, qui finalement entraine l’apparition des récepteurs de croissance apparentés. Ce nouveau réseau pourrait surcompenser le manque de récepteurs originaux, le rendant encore pire que le réseau original. En outre, l’équipe a trouvé que le réseau reprogrammé comprenait parfois la participation d’une autre molécule connue comme le récepteur de tyrosine kinase MET, qui se lie spécifiquement à l’un des frères.

Une fois que les chercheurs ont découvert comment le blocage était déjoué, ils ont entrepris de dresser une meilleure ligne de défense. Yosef Yarden et son équipe ont créé de nouveaux anticorps monoclonaux pouvant cibler les deux autres principaux récepteurs de croissance de la fratrie, nommés HER2 (la cible de l’Herceptin, le médicament contre le cancer du sein) et HER3. L’idée était de donner les trois anticorps simultanément – les deux nouveaux ainsi que l’anticorps anti-EGFR originel – pour anticiper une résistance au traitement. En effet, appliquer la trithérapie à des cellules cancéreuses isolées, les empêche d’accomplir la reprogrammation nécessaire pour continuer à recevoir les signaux de croissance.

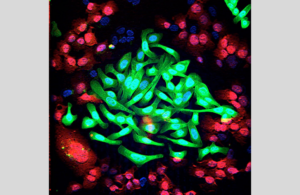

Ensuite l’équipe a essayé cette triple approche sur des modèles murins de cancer du poumon qui présentent la mutation secondaire résistante. Chez ces souris, la croissance tumorale a été presque complétement arrêtée. Des recherches plus poussées ont montré que ce traitement freinait la croissance des cellules tumorales sans agir sur celle des cellules saines.

Bien que des recherches complémentaires soient requises avant le démarrage d’essais cliniques, Yarden a bon espoir que cela changera non seulement le protocole de traitement pour le cancer du poumon mais aussi notre compréhension des mécanismes de résistance aux médicaments. « Les traitements par blocage d’une cible unique peuvent causer une boucle de rétroaction qui mène finalement à la récidive du cancer », dit-il. « Si nous pouvons prédire la façon dont la cellule cancéreuse va réagir quand on bloque les signaux de croissance dont elle a besoin pour continuer sa prolifération, nous pouvons prendre des dispositions en amont pour empêcher que cela n’arrive. »

Ont également participé à ces recherches, les docteurs Nadège Gaborit, Moshit Lindzen, Tomer Meir Salame du Département des Services Biologiques, et Ali Abdul-Hai du Centre Medical Kaplan ; et les étudiants Massimiliano Dall’Ora et Michal Sevilla-Sharon ; en coopération avec le Prof. Julian Downward de l’Institut de Recherche de Londres, UK.

Le Pr Yarden est le lauréat du prix Léopold Griffuel en Recherche Fondamentale, remis par l’association française majeure de lutte contre le cancer, appelée Fondation ARC pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

Publication dans Science Signaling,[:en]Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide, responsible for some 1.59 million deaths a year. That figure is due, in part, to the fact that the cancer often returns after what, at first, seems to be successful treatment. And the recurring cancer is often resistant to the chemotherapy and other drugs that originally drove it into remission. According to new research by the Weizmann Institute’s Prof. Yosef Yarden, a new strategy involving a three-pronged approach might keep an aggressive form of lung cancer from returning.

The research, says Yarden, arose out of some puzzling results of clinical trials. One class of relatively common lung cancers, which carry a particular mutation in a receptor on the cell membrane, called EGFR, can be treated with a sort of “wonder drug.” This drug keeps a growth signal from getting into the cell, thus preventing the deadly progression and spread of the cancer. But within a year, those with this mutation invariably experience new cancer growth, usually as a result of a second EGFR mutation. To prevent this from happening, researchers had tried to administer another drug, an antibody that is today used to treat colorectal cancer. This drug also obstructs the passing of the growth signal by stopping EGFR. Even though the antibody drug should have been able to effectively block the EGFRs – the growth receptors – including those generated by the second mutation, clinical trials of this drug for lung cancer did not produce results. “This finding ran counter to everything we knew about the way tumors develop resistance,” says Yarden.

How do the cancer cells manage to circumvent the blockade put up by an anti-EGFR antibody? In the new study, which appeared today in Science Signaling, Yarden and his student Maicol Mancini discovered what happens to cancer cells when they are exposed to the receptor-blocking antibody.

“The blocked receptor has ‘siblings’ – other receptors that can step up to do the job,” says Yarden. Indeed, the team found that when the main receptor (EGFR) continued to be blocked, one of the cell’s communication networks was rerouted, causing the siblings to appear on the cell membrane instead of the original receptor. The finely-tuned antibody did not block these, and thus the cancer cells were once again “in business.”

The researchers uncovered the chain of protein communication in the new network that ultimately leads to appearance of the sibling growth receptors. This new network may overcompensate for the lack of the original receptor, making it even worse than the original. In addition, the team found that the rewired network sometimes included the participation of another molecule, known as receptor tyrosine kinase MET, which specifically binds to one of the siblings. This signaling molecule is often found in metastatic cancers.

Once the researchers discovered how the blockade was breached, they set out to erect a better line of defense. Yarden and his team created new monoclonal antibodies that could target the two main growth receptor siblings, named HER2 (the target of the breast cancer drug Herceptin) and HER3.

The idea was to give all three antibodies together – the two new ones and the original anti-EGFR antibody – to preempt resistance to the treatment. Indeed, in isolated cancer cells, applying the triple treatment prevented them from completing the rewiring necessary for continuing to receive growth signals.

Next the team tried the three-pronged approach on mouse models of lung cancer that had the secondary, resistance mutation. In these mice, the tumor growth was almost completely arrested. More importantly, further research showed that this treatment reined in the growth of the tumor while leaving healthy cells alone.

Although much more research is required before the triple-treatment approach makes it to the clinic, Yarden is hopeful that it will change not only the treatment protocol for lung cancer, but our understanding of the mechanisms of drug resistance. “Treatment by blocking a single target can cause a feedback loop that ultimately leads to a resurgence of the cancer,” he says.

“If we can predict how the cancer cell will react when we block the growth signals it needs to continue proliferating, we can take preemptive steps to prevent this from happening.”

Also participating in this research were Drs. Nadège Gaborit, Moshit Lindzen, Tomer Meir Salame of the Biological Services Department, and Ali Abdul-Hai, also of Kaplan Medical Center; and research students Massimiliano Dall’Ora and Michal Sevilla-Sharon; together with Prof. Julian Downward of the London Research Institute, UK.

Prof. Yarden is the recipient of the 2015 Leopold Griffuel Prize for Fundamental Research, awarded by the major French association for fighting cancer, called ARC Foundation for Cancer Research.

Publication in Science Signaling,

[:]