Israël – Suisse : les coraux du golfe d'Aqaba résistent au réchauffement et pourraient être réensemencés

[:fr]Partout dans le monde, les récifs coralliens sont en pleine mutation et le réchauffement climatique entraîne leur extinction. Des scientifiques de l’Université Bar-Ilan en Israël sont impliqués dans une belle découverte concernant les coraux de la mer rouge. Les récifs coralliens du golfe d’Aqaba peuvent résister à des températures élevées de l’eau. Ces supers coraux de l’espèce Stylophora pistillata pourraient un jour réensemencer des récifs coralliens partout où les coraux meurent.

Le plus grand récif de la planète, la Grande barrière de corail d’Australie, connaît actuellement un énorme blanchissement des coraux. La disparition des récifs coralliens témoigne de la perte de certains écosystèmes parmi les plus diversifiés de la planète.

Or, les scientifiques de l’EPFL (Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne) et de l’UNIL (Université de Lausanne) en Suisse, de la Faculté Goodman des sciences de la vie à l’Université Bar-Ilan en Israël et de l’Institut interacadémique des sciences de la mer (Israël) ont montré que les coraux du golfe d’Aqaba au Nord de la mer Rouge sont particulièrement résistants aux effets du réchauffement climatique et à l’acidification des océans.

Pr Maoz Fine, Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat

& Goodman Faculty of Life Sciences, Bar-Ilan University, Israël

Les implications sont importantes, car le golfe d’Aqaba est un refuge de corail unique. Les coraux peuvent fournir la clé pour comprendre le mécanisme biologique qui conduit à la résistance thermique, ou la faiblesse qui sous-tend le blanchissement massif. On espère également que les récifs du golfe d’Aqaba pourraient être utilisés pour relancer les récifs détériorés dans la mer Rouge et peut-être même dans le monde.

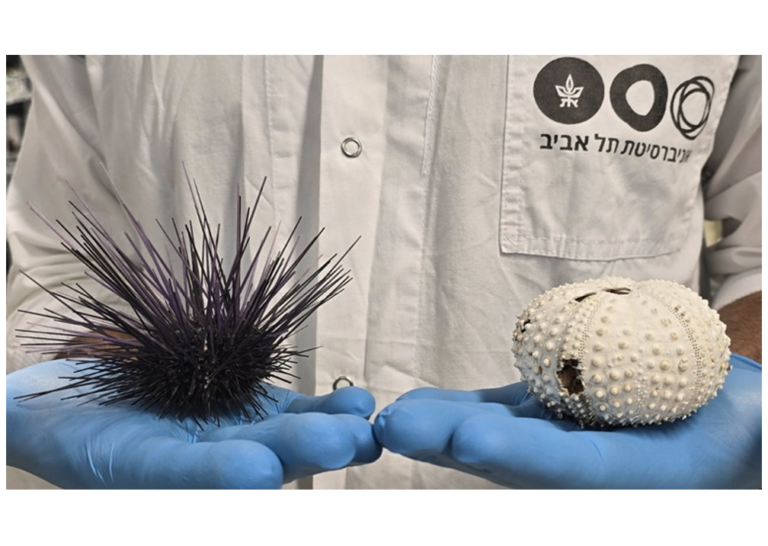

Les scientifiques ont effectué la première évaluation physiologique détaillée des coraux prélevés dans le golfe d’Aqaba après exposition à des conditions stressantes sur une période de six semaines. Ils ont constaté que les coraux n’avaient pas blanchi. « Dans des conditions similaires conditions, la plupart des coraux blanchiraient et mourraient« , explique Thomas Krueger, scientifique à l’EPFL. « Ces coraux vivent à des températures sous-optimales en ce moment et pourraient être mieux aptes à supporter le réchauffement futur de l’océan« .

« Ce récif devrait être reconnu internationalement en tant que site naturel de première importance, car il pourrait être l’un des derniers récifs à la fin de ce siècle« , explique Anders Meibom de l’EPFL et de l’UNIL. « Les pays du Golfe d’Aqaba, Israël, Arabie Saoudite, Egypte, Jordanie devraient créer un programme fort de protection environnementale, car même si ces coraux résistent à la hausse des températures de l’eau, ils sont sensibles à la pollution locale, à la surpêche… et ils doivent d’autant plus être protégés. »

À l’Institut inter-universitaire pour les sciences de la mer d’Eilat (Israël), des scientifiques ont exposé des Stylophora pistillata collectés dans le golfe d’Aqaba, à différentes températures de l’eau et à l’acidification. Les conditions ressemblent aux conditions en été d’un océan futur dans cette région si le réchauffement de l’océan local se poursuit à son rythme actuel d’environ 0,4 à 0,5 ° C par décennie. Ils ont vérifié la santé des principales fonctions physiologiques des coraux, mesuré des variables comme le métabolisme de l’énergie, la capacité de construire un squelette et l’échange de nutriments au niveau moléculaire entre les coraux et leurs symbiotes, les algues. Ces variables physiologiques n’ont pas été affectées par un traitement expérimental sévère. D’autres travaux sur des variables comme la fertilité ou la performance concurrentielle sont nécessaires.

Les coraux vivent en symbiose avec un partenaire algue, comme les humains sont en symbiose avec des bactéries intestinales. Comme les bactéries dans l’intestin aident à la digestion, fournissant des nutriments précieux au reste du corps, les algues qui vivent dans le partenaire corail fournissent des nutriments aux coraux. Les bactéries dans notre corps prospèrent dans notre tube digestif, tout comme les algues peuvent vivre dans leur partenaire corallien. Le blanchissement se produit lorsque les algues colorées sont éjectées par leur partenaire de corail, et la symbiose se décompose. Si les algues ne reviennent pas, le corail meurt.

Pré-acclimaté à la tolérance thermique

Le Stylophora pistillata qui se trouve dans d’autres régions du monde, et au-delà du golfe d’Aqaba, ne constitue pas nécessairement une résistance thermique. Le mécanisme biologique qui sous-tend la robustesse des récifs du Golfe d’Aqaba reste inconnu, mais les scientifiques pensent savoir comment les espèces ont évolué pour devenir thermiquement résistantes.

« Les coraux dans le golfe d’Aqaba sont pré-acclimatés à la tolérance thermique due à la géographie spéciale et à l’histoire récente de la mer Rouge« , explique le Pr Maoz Fine de la Faculté des sciences de la vie Mina et Everard Goodman de l’Université Bar-Ilan et l’Institut inter-universitaire des sciences de la mer.

À la fin de la dernière ère glaciaire, les coraux ont commencé à coloniser la mer Rouge grâce à la liaison sud avec l’océan Indien. Le goulot d’étranglement thermique à l’entrée sud avec des températures de l’eau en été augmentant de 30 à 32°C a créé une barrière sélective, les plus résistants se sont déplacés vers le nord. Or, cette population fondatrice résistante à la chaleur a rencontré beaucoup d’eaux plus fraîches une fois atteinte l’extrémité nord où se trouve le golfe d’Aqaba.

L’étude a émis l’hypothèse que ces coraux pourraient mieux faire face au réchauffement océanique, car ils ne sont pas seulement issus d’une population fondatrice sélectionnée par la chaleur, mais ils ont également commencé leur réchauffement à partir d’une température plus basse par rapport à leurs homologues du centre et du sud de la mer Rouge.

Mais en dépit de leur résistance au réchauffement climatique, les coraux du golfe d’Aqaba sont vulnérables à d’autres stress comme la pollution locale : pollution atmosphérique locale, nutriments des piscicultures, herbicides provenant du jardinage, peuvent réduire la tolérance exceptionnellement élevée des récifs du Golfe d’Aqaba.

Traduction/adaptation Esther Amar pour Israël Science Info

Publication dans la revue Royal Society Open Science, 17 mai 2017

A savoir : Le blanchissement des coraux est un phénomène au cours duquel le corail, animal aquatique vivant sous forme de colonie de polypes, expulse de sa texture les algues symbiotiques (les zooxanthelles, Symbiodinium) en raison du stress thermique. Les algues donnant leur pigmentation au massif corallien étant expulsées, le corail blanchit. La symbiose entre les polypes et les zooxanthelles (qui par la photosynthèse fournissent leur nourriture au corail) étant interrompue, le corail meurt. geoblog[:en]Israeli researchers of Bar Ilan University are involved in a major breakthrough. Coral reefs in the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba can resist rising water temperatures. If they survive local pollution, these corals may one day be used to re-seed parts of the world where reefs are dying. The scientists urge governments to protect the Gulf of Aqaba Reefs.

Coral reefs are dying on a massive scale around the world, and global warming is driving this extinction. The planet’s largest reef, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, is currently experiencing enormous coral bleaching for the second year in a row, while last year left only a third of its 2300-km ecosystem unbleached. The demise of coral reefs heralds the loss of some of the planet’s most diverse ecosystems.

Pr Maoz Fine, Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat

& Goodman Faculty of Life Sciences, Bar-Ilan University, Israël

Now, scientists at EPFL (Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne) and UNIL (Université de Lausanne) in Switzerland, and the Mina and Everard Goodman Faculty of Life Sciences at Bar-Ilan University and the InterUniversity Institute of Marine Sciences in Israel, have shown that corals in the Gulf of Aqaba in the Northern Red Sea are particularly resistant to the effects of global warming and ocean acidification. The results were recently published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

The implications are important, as the Gulf of Aqaba is a unique coral refuge. The corals may provide the key to understanding the biological mechanism that leads to thermal resistance, or the weakness that underlies massive bleaching. There is also the hope that the Gulf of Aqaba Reefs could be used to re-seed deteriorated reefs in the Red Sea and perhaps even around the world.

The Scientists performed the very first detailed physiological assessment of corals taken from the Gulf of Aqaba after exposure to stressful conditions over a six-week period. They found that the corals did not bleach.

“[Under these conditions,] most corals around the world would probably bleach and have a high degree of mortality,” says EPFL scientist Thomas Krueger. “Most of the variables that we measured actually improved, suggesting that these corals are living under suboptimal temperatures right now and might be better prepared for future ocean warming.”

At the InterUniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat, scientists exposed corals of the species Stylophora pistillata, collected from the Gulf of Aqaba, to water temperatures and acidification. The conditions resemble the summer conditions of a future ocean in this region if local ocean warming continues at its current rate of approximately 0.4-0.5°C per decade. They performed an overall health check of all the major physiological functions of the corals, measuring variables like energy metabolism, the ability to build a skeleton, and nutrient exchange at the molecular level between the coral-host and their algae symbionts. These physiological variables were mostly unaffected by the harsh experimental treatment. Still, further work on ecologically relevant variables like fertility or competitive performance is needed.

Symbiotic corals live together with an algae partner, much in the same way humans are in symbiosis with gut bacteria. Just as bacteria in the gut aid with digestion, providing valuable nutrients to the rest of the body, the algae that live within the coral-partner provide nutrients to the corals. The bacteria in our body thrive within our digestive tract, just as the algae benefit from living within the coral partner. Bleaching occurs when the colored algae are ejected by their coral-partner, and the symbiosis breaks down. If the algae do not return, the coral dies.

Pre-acclimated to thermal tolerance

The coral species Stylophora pistillata occurs in other regions of the world, and beyond the Gulf of Aqaba, does not necessarily demonstrate thermal resistance. The biological mechanism that underlies the robustness of the Gulf of Aqaba Reefs is still unknown, but the scientists have an idea of how the species evolved to become thermally resistant.

“Corals in the Gulf of Aqaba are pre-acclimated to thermal tolerance due to the special geography and recent history of the Red Sea,” says scientist Prof. Maoz Fine of Bar-Ilan University’s Mina and Everard Goodman Faculty of Life Sciences and the InterUniversity Institute of Marine Sciences.

At the end of the last ice age, corals started recolonizing the whole of the Red Sea through the southern connection to the Indian Ocean. The thermal bottleneck at the southern entrance with summer water temperatures rising to 30-32°C provided a selective barrier, allowing only highly resistant individuals to move north. Ironically, this heat-resistant founding population encountered much cooler waters once reaching the northern end, where the Gulf of Aqaba is located.

Based on this, the study hypothesized that these corals might be able to better cope with today’s ocean warming, considering that they not only descended from a heat-selected founding population, but they also started their warming trajectory from a lower temperature, compared to their counterparts in the central and southern Red Sea.

Protection of the Gulf of Aqaba Reef

Despite being resistant to global warming, the corals from the Gulf of Aqaba are still vulnerable to other stresses like pollution. “Local disturbances, such as local oil pollution, nutrients from fish farms, herbicides from gardening, may reduce the exceptionally high tolerance of the Gulf of Aqaba Reefs,” says Fine.

“This reef should receive international recognition as a natural site of great importance, because it might very well be one of the last reefs standing at the end of this century,” says Anders Meibom of EPFL and UNIL. “I would like to encourage the countries around the Gulf of Aqaba – Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan and Israel – to get together and create a strong protection environmental program, because even if these corals are resistant to rising water temperatures, they are still sensitive to local pollution, overfishing etc, and they need to be protected from this now.”

Publication in Royal Society Open Science, May 17th 2017[:]