Hadassah Brain Mapping Has Important Implications for Early Alzheimer’s Diagnosis

Using an innovative brain mapping technique, the Hadassah Medical Organization’s neuropsychiatry specialists have identified a cognitive process that has important implications for understanding the disorientation experienced by Alzheimer’s patients.

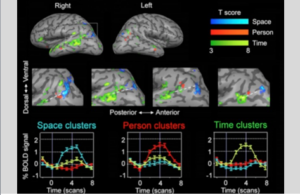

Using high-resolution functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), the neuroscientists, led by Dr. Shahar Arzy, Director of Hadassah’s Computational Neuropsychiatry Laboratory, discovered that the human brain has a highly ordered dedicated system that manages “orientation”–the brain function that enables us to know where we are in time and space and social relationship. It is this orientation system that allows an individual to form an internal representation of his external world.

HMO’s researchers also discovered that this orientation system overlaps another system called the “default mode network,” which is involved with processing the individuals’ sense of self in relation to time, space, and other people.

”We hypothesized that Alzheimer’s disease is a disorder of orientation,” relates Dr. Arzy, “where people lose their way on the cognitive maps of memory, places, and later people. Moreover, the default mode network, overlapping with the orientation system, is known to be the network which is disturbed in Alzheimer’s disease.”

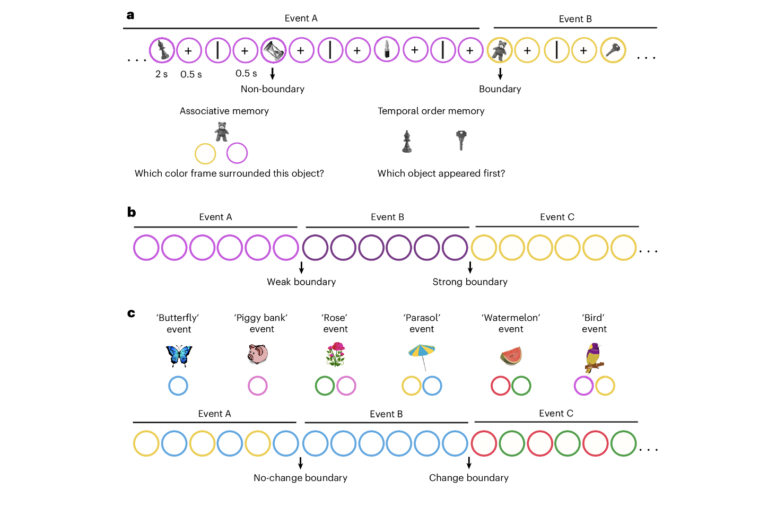

Dr. Arzy’s team recorded the brain function of 16 individuals, who compared their subjective distance to different places, events, and people. When the researchers analyzed the results, they saw that a local set of structures within the brain were activated that were related to orientation in space, time, and person. A particular pattern of activity was triggered in each person’s brain. The activations were near one another and partially overlapping, illustrating the links among a person’s orientations in space, time, and social relations. At the same time, this activity overlapped with the brain’s default mode network.

Dr. Arzy reports that his team is now working to develop new computational tests and functional neuroimaging examinations to establish a very early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Currently, Dr. Arzy notes, there is no exact understanding of the core pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. No one has been able to elucidate the neurocognitive mechanism that underpins the variable functional loss that affects people with this disease. Consequently, he says, “by the time we neurologists diagnose the disease, it’s too late to treat effectively. He concludes, however, that “our efforts will enable us to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease much earlier in the process and then be able to begin treating it effectively.”

Publication in PNAS, July 16, 2015